Sam Gilbert, Mark Fabian, and Roberto Foa draw on data from the first UK lockdown to illustrate how well-being levels improved, contrary to what may have been expected. They nevertheless explain that such improvements were not evenly distributed among the population and discuss the policy implications of their findings.

In the second quarter of 2020, the period of the UK’s first COVID-19 lockdown, suicides were down 36% year-on-year. In fact, according to provisional data released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the suicide rate was the lowest for any quarter since the ONS started publishing data on suicides in 2001. What can explain this sharp fall? The ONS cautions that it probably reflects disruption to the coroner’s service during the pandemic, rather than a genuine reduction in suicides. But our research raises a surprising alternative possibility: people are happier under lockdown.

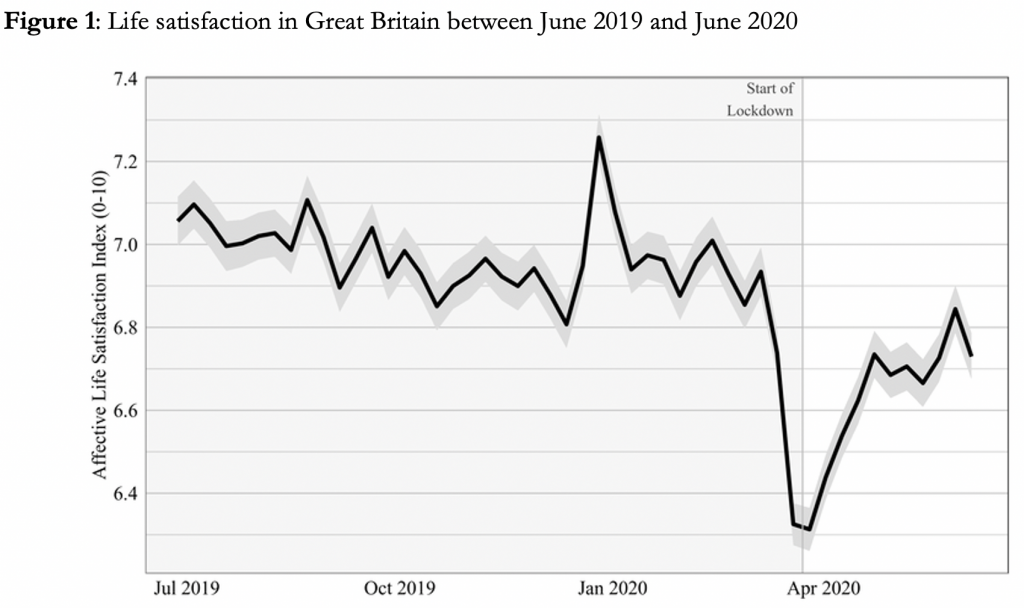

At first this claim seems counterintuitive – provocative, even. However, it’s supported by analysis of two complementary datasets: YouGov’s weekly mood tracker and Google Trends. Since June 2019, YouGov has surveyed a representative sample of 2,000 Brits each week, asking them to report on a range of mood states. This data shows that while the onset of the pandemic had a very negative effect on mood, the implementation of lockdown quickly restored people’s subjective well-being to its pre-pandemic baseline. Sadness, fear, and stress all fell during lockdown; and although boredom, loneliness, frustration, and apathy increased, so did happiness, optimism, inspiration, and contentment.

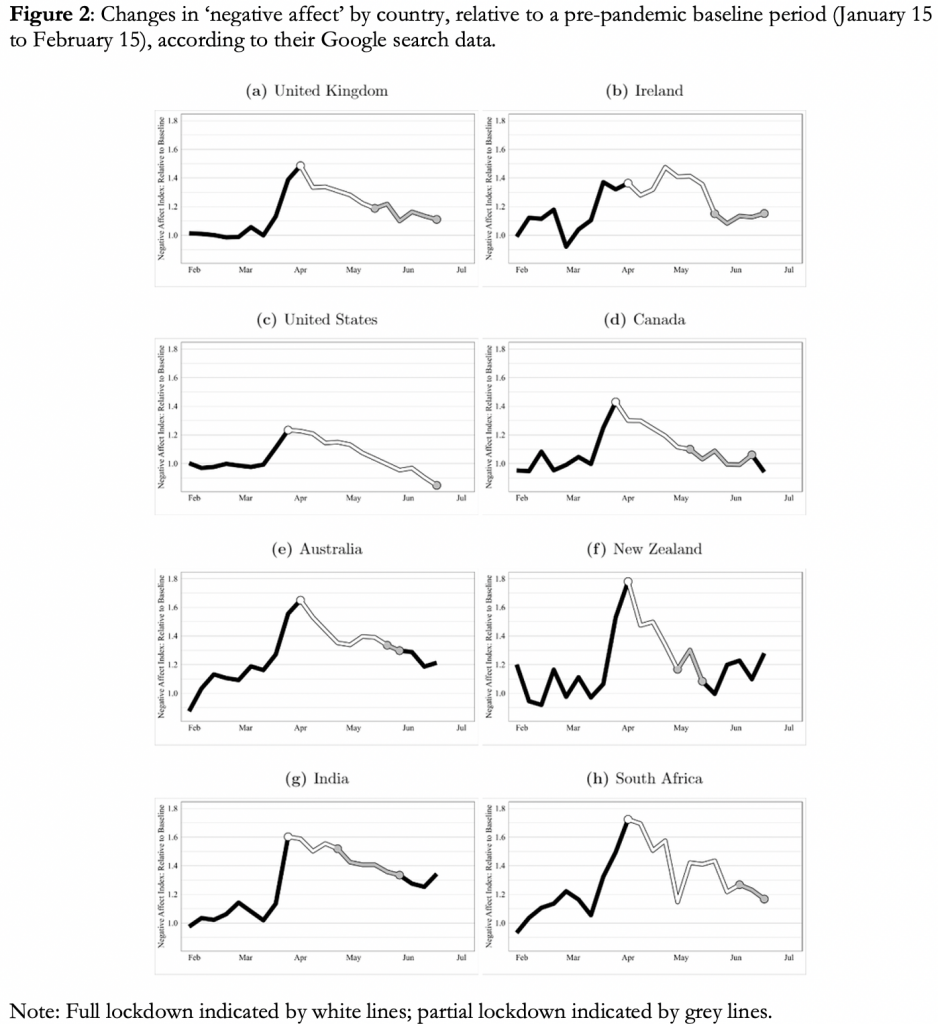

The remarkable recovery of people’s subjective well-being under lockdown seems not to have been confined to the UK. Google searches for negative emotions turn out to be highly correlated with the YouGov mood tracker, meaning that so-called ‘negative affect’ in different countries can be compared using Google Trends. In New Zealand, Australia, India, South Africa, Ireland, the USA and Canada, Google data suggests that negative affect spiked as the pandemic took hold, but began to fall as soon as lockdowns and shelter-in-place orders were implemented.

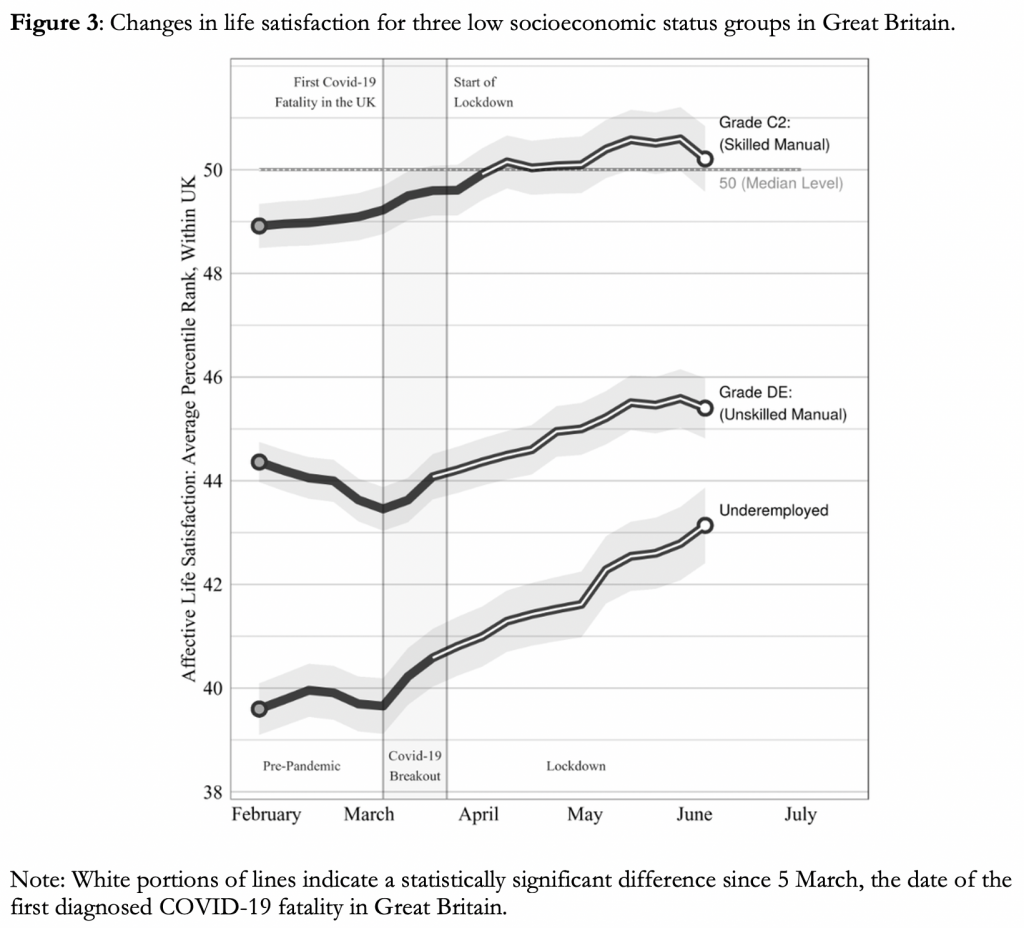

Of course, saying that people were happier under lockdown does not imply that everyone was happier. In fact, improvements in well-being during the period of the first UK national lockdown were not evenly distributed. The YouGov data shows things were markedly worse for the elderly and women living alone, and somewhat worse for professionals. On the other hand, things were significantly better for low socioeconomic status men, whose overall life satisfaction increased more than any other group.

As men of low socioeconomic status are one of the highest risk groups for completed suicide attempts, the relative improvement in their mental health during lockdown may help explain the unexpected reduction in suicide rates during Q2.

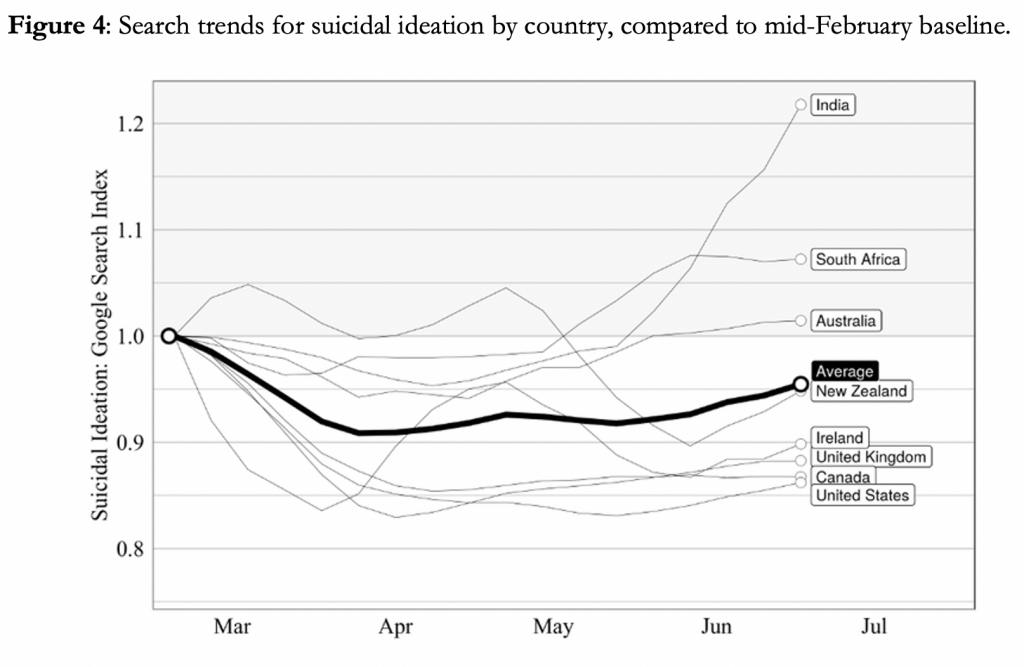

We suspect that the exceptional welfare support measures put in place during the UK’s first national lockdown alleviated many of the conditions which can prompt individuals to act on suicidal feelings – including eviction and homelessness, workplace bullying and stress, and problems keeping up with debt repayments. International comparisons seem to support this view. When we looked at suicide-related Google searches by country, India and South Africa were the outliers. Both countries implemented lockdowns with minimal social support mechanisms and saw a steep rise in suicide-related search rates. Elsewhere, suicide-related search during lockdown was flat or falling relative to its pre-pandemic baseline.

The immediate policy implications in terms of the pandemic response are clear. Despite widespread concerns, mental health costs are not a reason to avoid implementing local or national lockdowns – provided that income support measures such as furlough schemes remain in place. Meanwhile, policy interventions aimed at mitigating the negative effects of lockdown on well-being should prioritise the needs of women living alone and the elderly. With this is mind, support bubbles and revisions to the guidance on shielding are to be welcomed.

But there are also longer-term implications of the findings from this natural experiment. They hint both at the damage stressful working environments, housing insecurity, and indebtedness may be doing to well-being, and at the opportunity for policy innovations which strengthen the social safety net to deliver real improvements to people’s happiness.

___________________

Sam Gilbert is an Affiliated Researcher with the Bennett Institute for Public Policy, University of Cambridge.

Mark Fabian is a welfare economist working on the Measuring Well-Being project at the Bennett Institute for Public Policy, University of Cambridge.

Roberto Foa is a University Lecturer in politics and public policy at POLIS, University of Cambridge.

Photo by chaitanya pillala on Unsplash.

This seems hard to fathom. Organisations such as Mind have been flooded with new enquiries from people seeking help with their mental health due to lockdown. That on top of a rise in mental ill-health among its existing user base. Anecdotal yes, but I can cite three suicides of friends /acquaintances since last April. That is a spike.

I am very sorry for your loss Paul. With this study, we have tried to separate the well-being effects of lockdown from the well-being effects of the pandemic (the full report explains how). The pandemic has clearly had a very negative impact on mood – our analysis suggests that lockdown policies mitigate this, rather than accentuating it. We also note that the overall improvement in well-being during the first lockdown in the UK was not evenly distributed.

This seems very short term considering all those problems have been pushed into 2021. When evictions and job losses increase in 2021 and all the support evaporates and massive tax increase and austerity occur associated harms are likely to increase. Not to mention suicides have risen significantly in South Korea and japan. People in the most vulnerable positions have been pushed into massive debt, evictions will start very soon, and the harm will be significant for many years beyond the end of the virus

Thanks for your comment Kieran. I think we are clear in the blog (and in the report it’s based on) that well-being under lockdown is contingent on income support measures. I’d be interested in the suicide data from South Korea and Japan that you refer to – could you send a link?