UK cities currently have limited control over the majority of their finances, significantly constraining their ability to target investment where it is needed most and preventing them from retaining the benefits of encouraging local growth. Andrew Carter argues that we can no longer afford a high degree of centralisation as the status quo; fiscal devolution to cities is necessary.

UK cities currently have limited control over the majority of their finances, significantly constraining their ability to target investment where it is needed most and preventing them from retaining the benefits of encouraging local growth. Andrew Carter argues that we can no longer afford a high degree of centralisation as the status quo; fiscal devolution to cities is necessary.

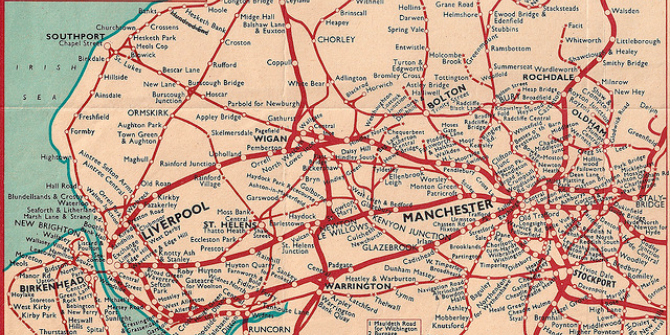

There has been an unprecedented level of interest over the past year from all sides of politics in the disparities between the economic performance of London and other cities in the South of England and those in the rest of the country. And yet, this ‘North-South’ divide is by no means a recent phenomenon. As our Cities Outlook 2015 report shows, the gap between our best- and worst-performing cities has been widening dramatically over many years, giving rise to a staggering scale of challenge as we look ahead to the next Parliament.

It is clear from only a cursory glance at the findings of Cities Outlook, which tracks city economies between 2004 and 2013, that national growth over the past decade has largely been driven by only a handful of cities – mainly located in the South. The populations of cities in the South have expanded at twice the rate of cities elsewhere in the UK, while the number of businesses increased by almost 27 per cent in southern cities, compared to 14 per cent in other UK cities. And for every 12 net new jobs created between 2004 and 2013 in the South of England, only one was created in cities in the rest of Great Britain.

Such stark differences in performance may come as a surprise to many, given that boosting growth across the country has been a major theme of British politics throughout the last decade. Over this time, successive Labour administrations and the current coalition government have introduced an array of policy interventions designed to support cities and their surrounding areas to improve the economic prospects of their residents and their contribution to the national economy. And yet, as the data so clearly reveals, despite bold ambitions and good intentions, the policy response to the rapidly changing global economic landscape has been largely inadequate. Across successive governments, local growth policies have tended to be small in scale, ad hoc, and most crucially, have kept decision-making power within Whitehall, rather than transfer it to cities themselves.

It is greater London, the city-region with the greatest powers over its own strategic planning, transport and infrastructure, which stands out as the UK’s strongest city-region – with a halo of influence that has seen the cities of the South leave their Northern counterparts in their wake. While the level of power wielded by the capital is limited by international standards, it has proved important in allowing its policy-makers to respond to the pressures of growth, and to comprehensively plan for the future.

London’s successes underpin why the recent agreement hammered out with greater Manchester is so welcome, and why such flexibilities must be extended to other cities as an urgent priority by whichever party wins the forthcoming general election. But devolution to cities and city-regions doesn’t just need to be widened – it should be deepened too, through taking decisive action on fiscal devolution.

Our cities currently have limited control over the majority of their finances – including over the taxes they raise and how they can choose to spend them. The OECD estimates that, on average, 17 per cent of the money that UK councils spend is raised through local taxes. The average across the rest of the OECD is 55 per cent, with the level of taxes controlled locally or regionally being about 10 times greater in Canada, seven times more in Sweden, and nearly six times more in Germany. These discrepancies matter, because they significantly constrain the ability of UK cities to target investment where it is needed most, and prevent them from retaining the benefits of encouraging local growth. What’s more, in an age of austerity, fiscal devolution could also incentive local governments to find new, more cost-effective ways of delivering public services.

Opponents of this kind of devolution cite the risk of UK cities overextending themselves financially and going bust, the likelihood of increased postcode lotteries and inequalities developing between places, and the impact it could have on central Government’s ability to redistribute tax receipts from one part of the country to another. But arguments in favour of modest amounts of devolution over strategic planning or the local tax base are not mutually exclusive to recognising the important job that redistribution plays in national systems of welfare, employment support and a whole host of services. Certainly, there are many significant policy areas that will continue to be best placed with Westminster.

And yet, as the data in this year’s Cities Outlook shows, a UK economy built on two tiers of progress and decline can no longer afford a ‘steady as it goes’ approach, with total centralisation as the status quo. This is why any party serious about making significant headway against the deficit, delivering widespread prosperity, and building a sustainable national economy, must ensure that fiscal devolution to the UK’s cities forms a critical part of their policy platform for May 2015.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: Ozz13x CC BY 2.0

Andrew Carter is Acting Chief Executive of the Centre for Cities. He can be found on Twitter @AndrewCities.

Andrew Carter is Acting Chief Executive of the Centre for Cities. He can be found on Twitter @AndrewCities.