Economic news uses recognizable experts to describe the government’s fiscal position, a necessary first step in justifying to citizens how the government borrows and spends. Catherine Walsh argues that press text constructs expert judgments as superior by representing the experts as properly positioned to judge, not by representing their judgments as being better informed.

Economic news uses recognizable experts to describe the government’s fiscal position, a necessary first step in justifying to citizens how the government borrows and spends. Catherine Walsh argues that press text constructs expert judgments as superior by representing the experts as properly positioned to judge, not by representing their judgments as being better informed.

Support for austerity was based in part on how news journalists used well-known experts to certify the government’s borrowing and spending. Journalists used these experts as sources, but rarely used them to question, criticise, or even just explain the government’s fiscal plans or outcomes.

In recent research I studied how UK newspapers used experts in economic and political news between 2010 and 2016. I wanted to learn how commonly experts were cited and what they were ‘doing’ inside these articles. Surprisingly, I found that fiscal experts are not characterised in newspapers as having technical knowledge, deep understanding, or superior judgment. Instead, journalists describe them by citing social cues like general esteem or sovereignty from other elites, especially government elites. And the more likely an expert is to be associated with the word ‘austerity’ in a newspaper article, the less likely that expert is to be critical in it.

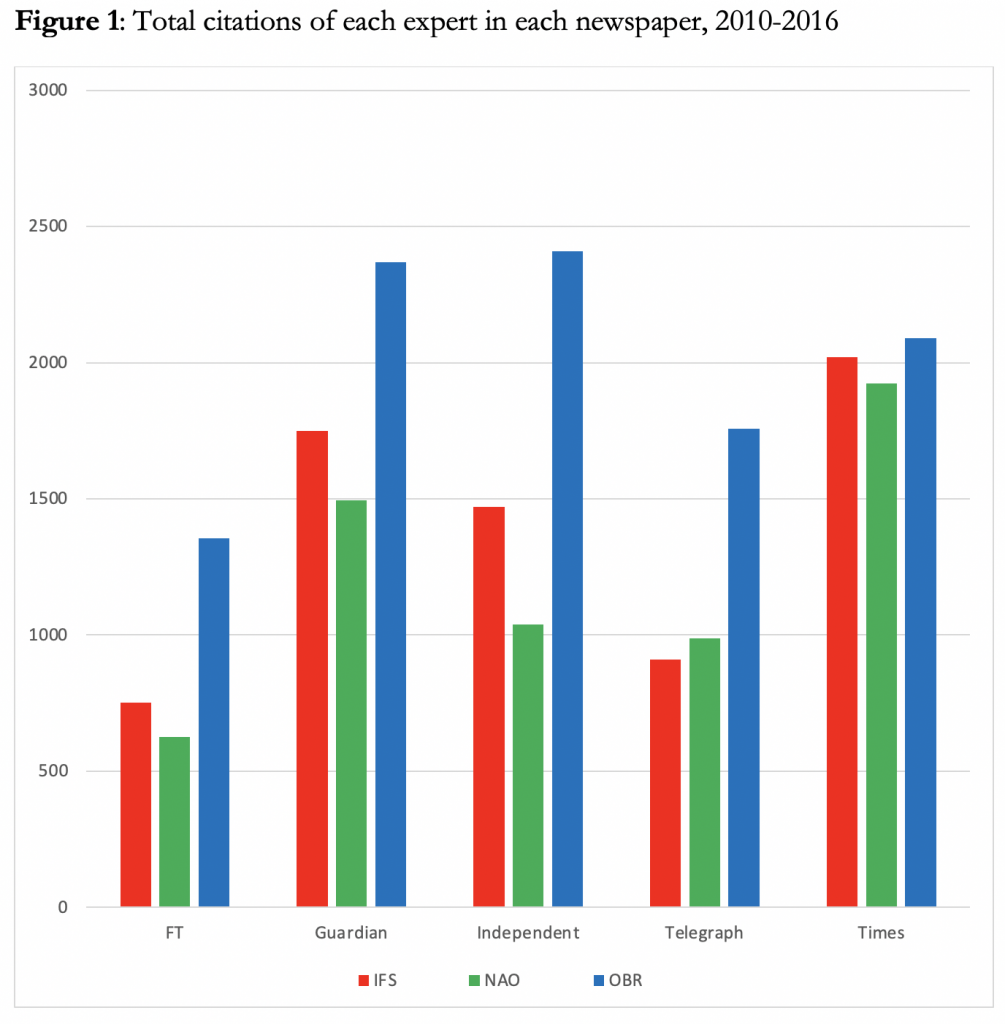

I collected over 20,000 articles published in the Financial Times, Independent, Guardian, The Daily Telegraph, and Times throughout the Coalition government’s time in office. The experts I chose were the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), the National Audit Office (NAO) and the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). All three are conspicuous experts with a wide reach and considerable analytic resources, and are used as trusted sources by the British press.

The three expert bodies have similarities and differences. The NAO is a very large government body that certifies the national public accounts and passes judgment on the government’s efficient and effective use of public funds. The OBR is a very small office that estimates tax and welfare costs, creates forecasts, and interprets the consequences of fiscal policy against targets set for it by the Treasury. Finally, the IFS is a non-governmental micro-economic think tank that costs how state policies affect the finances of individuals, families, generations, communities, firms, and government itself. They all provide regular, broad, technical oversight of UK government finances and fiscal management.

Journalists find the credibility of fiscal experts very useful. Figure One shows that the proportion of articles citing the experts is broadly comparable from the left- to the right-wing of the ideological spectrum. Moreover, almost all newspapers favoured the OBR compared to the other two bodies, with the exception of the Times, which cited the three experts almost equally. Overall, the OBR was cited in almost 10,000 articles over the first six-and-a half years of its lifetime, compared to approximately 6,000-7,000 articles for the NAO and IFS.

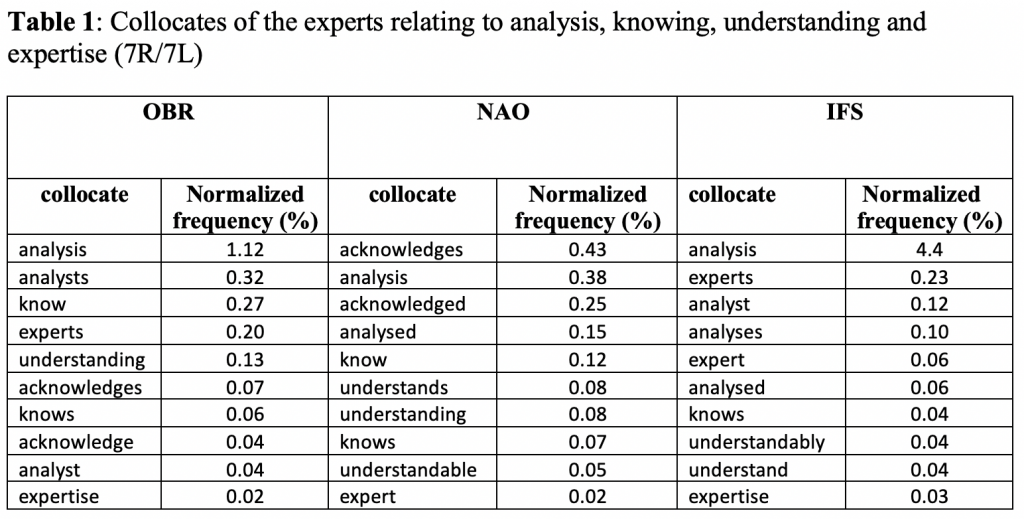

Even though fiscal management requires significant specialist knowledge and understanding, words signifying knowing and understanding are very rarely associated with these experts in news. For each expert, Table One shows collocates (words that appear together with a strong statistical likelihood that the association is meaningful) of the discovered variants of analysis, knowing, understanding, and expertise. The normalized frequencies (the number of times the word appears next to the expert divided by the total citations of the expert) are very low indeed. In other words, these experts are rarely found within seven places of such collocates in the text, with the exception of the IFS and OBR being identified with the word ‘analysis’ in greater than once in one-hundred citations.

So, if the experts are not characterised as knowing or understanding things in these newspaper articles, then how are they described? The Treasury-appointed OBR is most consistently described as being ‘independent’, at 14.8% of the time, and 12.3% of OBR articles included the metaphor ‘watchdog’. The non-governmental IFS is also described as ‘independent’, albeit half as often at 7.6%. Readers are similarly reminded 4% of the time that the IFS is ‘respected’. The metaphor most consistently associated with the NAO is ‘watchdog’ at 2.6% of instances. But the NAO is most distinctive because of the verbs it is associated with: ‘criticizing’ (4%), ‘warning’ (3.4%) and ‘damning’ (1.3%). The other two experts are rarely seen in the company of such negative verbs, making the NAO the most critical in print.

This last point, about who warns or criticises, is particularly consequential because of the word austerity. Austerity is common, found in approximately one-third of the news stories, but there were two curious aspects to its life in text. Firstly, it does not cluster very closely (within seven word places) to any of the expert bodies. The consistent presence of ‘austerity’ elsewhere in the articles suggests that the experts are routinely being used by the journalists within a wider political context of public spending cuts, borrowing, and debt. Yet there is no evidence here of experts making direct comment on austerity. The association between the two are being left more implicit than that – what media scholars would call a frame.

And there is another curious disparity. IFS articles mention austerity almost as often as OBR articles do, 41% and 45% of articles, respectively. But NAO articles use the term eight times less often, at only 5.6%. In other words, although the (much less negative) IFS and the OBR both appear nearly equally frequently in articles with austerity, the (much more critical) NAO is seven to eight times less likely to do so.

Journalists use experts to enhance their own credibility and to frame stories with important, current, contentious issues. But if these fiscal experts do have wisdom to share with citizens based on their analytic capacity and access, then they are underutilized in British newspapers. Instead, readers are explicitly told to trust these experts based on their social standing. Implicitly, readers are also given to understand that these experts and their judgments are relevant to austerity as a national predicament. What readers – and citizens – do not get from experts in their press is scrutiny, challenge, or criticism of this most significant fiscal choice.

_____________________

Note: The above draws on the author’s published work in Journalism Studies.

Catherine Walsh is a Lecturer in the School of Journalism, Media and Culture (JOMEC) at Cardiff University, where she researches fiscal technocracy and how elites construct knowledge for each other and for the rest of us.

Catherine Walsh is a Lecturer in the School of Journalism, Media and Culture (JOMEC) at Cardiff University, where she researches fiscal technocracy and how elites construct knowledge for each other and for the rest of us.

Photo by Bank Phrom on Unsplash.