Looking at data showing voting intentions for an in/out EU referendum coupled with self-described national identity, Richard Wyn Jones finds that England is the most Eurosceptic part of Britain and the English the most Eurosceptic national group. In England, those with a more exclusively British sense of national identity are in fact the most pro-European and UKIP is concentrated among those with the most exclusively English sense of national identity. The timing of the European elections and the independence referendum is therefore very important, and UKIP may transform itself into another English National Party.

Looking at data showing voting intentions for an in/out EU referendum coupled with self-described national identity, Richard Wyn Jones finds that England is the most Eurosceptic part of Britain and the English the most Eurosceptic national group. In England, those with a more exclusively British sense of national identity are in fact the most pro-European and UKIP is concentrated among those with the most exclusively English sense of national identity. The timing of the European elections and the independence referendum is therefore very important, and UKIP may transform itself into another English National Party.

‘British Euroscepticism’ is a recurrent theme in political and scholarly debate within the UK as well as in political and scholarly debate abroad. This in many ways understandable preoccupation with ‘British Euroscepticism’ hides or occludes a much more differentiated pattern of attitudes across Britain towards the European Union. More specifically, there are some strikingly differentiated attitudes towards Europe both within and between the different national territories of Britain (I do not intend to say anything about Northern Ireland but will rather focus on territorial differences across Britain). These different attitudes may well end up having significant political effects.

What is Euroscepticism?

There is not, as far as I am aware, an agreed definition of Euroscepticism. Rather it is a terms that is applied to a number of different, if related, attitudes including, inter alia:

- An expressed intention to vote No in any referendum on continuing EU membership;

- A suspicion of ‘Europe’ and all its works;

- A propensity to vote for UKIP; etc.

We will return to all of these in a moment. But before doing so let me make clear my first and most important claim. No matter what we understand by Euroscepticism, England is the most Eurosceptic part of Britain and the English the most Eurosceptic national group.

National identities and attitudes towards EU membership

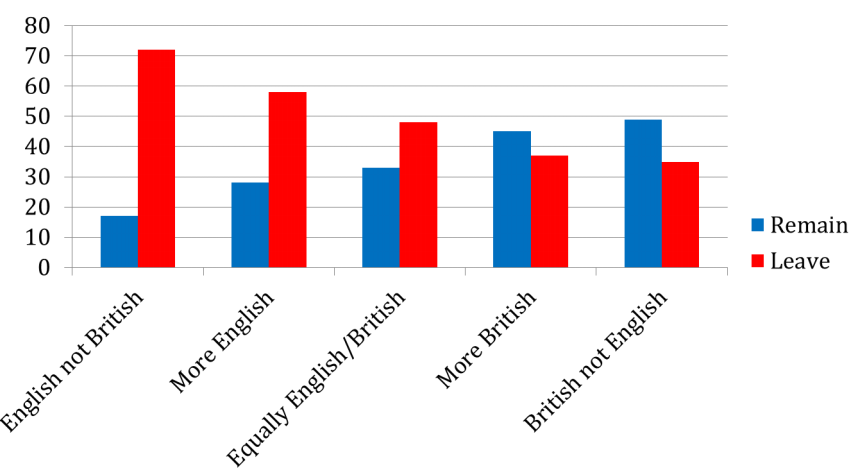

Figure 1 is based on data from the 2012 Future of England Survey and shows how respondents would have voted if a referendum on EU membership had been held in November 2012.

Figure 1: Vote in referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union by Moreno National Identity, England only, 2012 (%)

Source: FoES 2012

There are two points to note:

1. The extent of overall support in England for withdrawal is very striking. In fact, at this point (in November 2012) 50% of people in England would have voted to withdraw, 30% to remain member, with the remaining 20% divided between the Don’t Knows and the Wouldn’t Votes. It should be noted that more recent polling evidence suggests that this may have been a period of particularly strong Eurosceptic sentiment – but still… Attitudes in England are certainly very different from attitudes elsewhere in Britain. In crude terms, attitudes in Scotland are almost a mirror image of attitudes in England whilst Wales sits somewhere between the two.

2. Support for withdrawal in England is very much stronger among those with a more exclusive English sense of national identity whilst (pace much Eurosceptic rhetoric) those with a more exclusively British sense of national identity are in fact the most pro-European!

National identities and attitudes towards EU influence

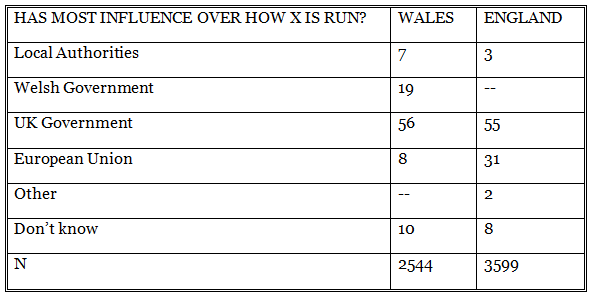

National differences in attitudes towards the EU are nicely illustrated in Table 1 which shows that, on average, people in England are far more likely than people in Wales to regard the EU as playing the dominant role in determining how their country. Indeed, roughly one third of English voters view the EU has having most influence (a figure that rises to fully 69% among UKIP supporters.) That this influence is regarded in wholly negative terms is underlined when we recall than this third would vote to leave the EU by a margin of some 8 to 1. Put in other words, it appears that around one in three of the English electorate are hard-core Eurosceptics. The proportion is much lower in Wales (and, indeed, Scotland and – to the extent that data is available – across the rest of western Europe.)

Table 1: Perceptions of EU influence: Wales and England compared (%)

Source: Welsh Referendum Survey 2011, FoES 2012.

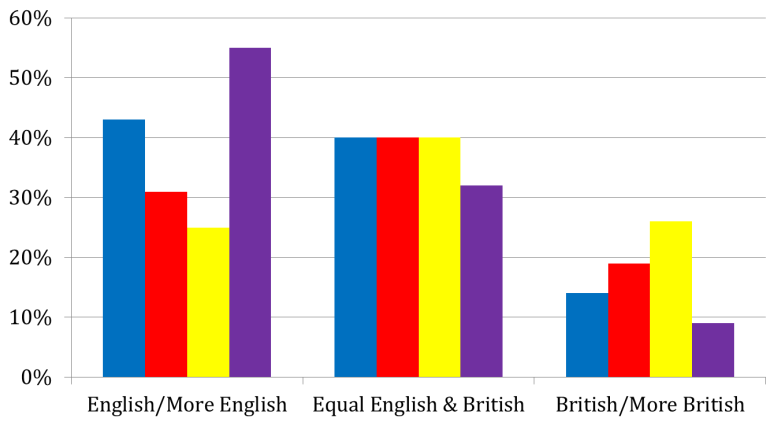

National Identities and Voting Intentions

That Scotland and Wales are two of UKIPs weakest regions has been confirmed in every European election since 1999. Specifically, Scotland is the weakest and Wales is the party’s second or third weakest region. But as is clear from Figure 2, even within England, UKIP is concentrated among those with the most exclusively English sense of national identity. (Which incidentally helps explain why London – the part of England with the weakest sense of English and strongest sense of British identity – has been another weak spot for Nigel Farage’s party.) By some contrast, in Wales evidence suggests that UKIP support is weakest among those with a more exclusively Welsh sense of national identity and strongest among those who feel most exclusively British. One might reasonably expect the situation in Scotland to resemble that in Wales in this regard.

Figure 2: England: Moreno national Identity by Voting Intention, 2012 (%)

Note: Blue=Conservative Party; Red=Labour; Yellow=LibDems; Purple=UKIP

Does any of this have possible political implications?

1. The timing of the European elections and the Scottish independence referendum. The former will be followed less than 4 months later by the latter, and what price the following result to set up the European poll: UKIP win in England, the SNP in Scotland and Labour in Wales? Might such a result – and in particular the response in London to it – have a bearing on the result of the subsequent independence referendum? It might. Some polling evidence suggests that the Yes side in Scotland is strengthened if it appears that UK heading for exit…

2. Territorial tensions within UKIP? My colleagues and I have argued that UKIP is, de facto, the English National Party. Given the different profiles of party supporters (and almost certainly activists) in England as compared to Wales and Scotland, what are the implications for the party as it apparently moves to embrace this position more self-consciously by championing English devolution?

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Professor Richard Wyn Jones is Director of the Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University. wynjonesr@cardiff.ac.uk

The Future of England Survey data is analysed in detail here.

It is quite simple, Scots and Welsh nationalists are more concerned about the perceived rule from London than from Brussels. They see the EU as a source of funds and a means of being recognised as a member state if independence can be achieved.

This view is quite deep rooted and it may blind those who hold it to the fact that Brussels may ultimately acquire a tighter and less democratic grip on them than London.

Yes, national identity is important in explaining Euroscepticism in Britain, but to understand why attitudes have become more hostile to membership during the Eurozone crisis and the domestic recession, the relationships involving economic variables and declining mainstream party influence are also crucial.

There seems a more general fixation among British academics on the rather static national identity variable in explaining public support for the EU (as well as conflating EU support with UKIP support). Behind this lies a generally dismissive normative appraisal of public opinion on EU membership: it’s uninformed and uninterested. Isn’t this changing now?