Dominic Abrams, Jo Broadwood, Fanny Lalot, and Kaya Davies Hayon present the findings of research examining whether people from across the UK found communication about COVID-19 honest and credible, empathic, clear, accessible, and whether it met the needs of their community. They find that both UK and local government communications were perceived on average as fairly clear and as using understandable language, but that significant differences exist on other measures.

In Gershwin’s song ‘It Ain’t Necessarily So’ from the musical Porgy and Bess, we learn that just because an authoritative source tells us something, it isn’t necessarily true. Scepticism might be a national characteristic, but during this pandemic the public has been more dependent on the UK government for information and guidance than most people have ever experienced. The government has provided a prodigious volume of statistics, often updated daily, as well as a plethora of new legal requirements, advisory statements and sometimes projections. But how have the public viewed these efforts and why might they doubt their value?

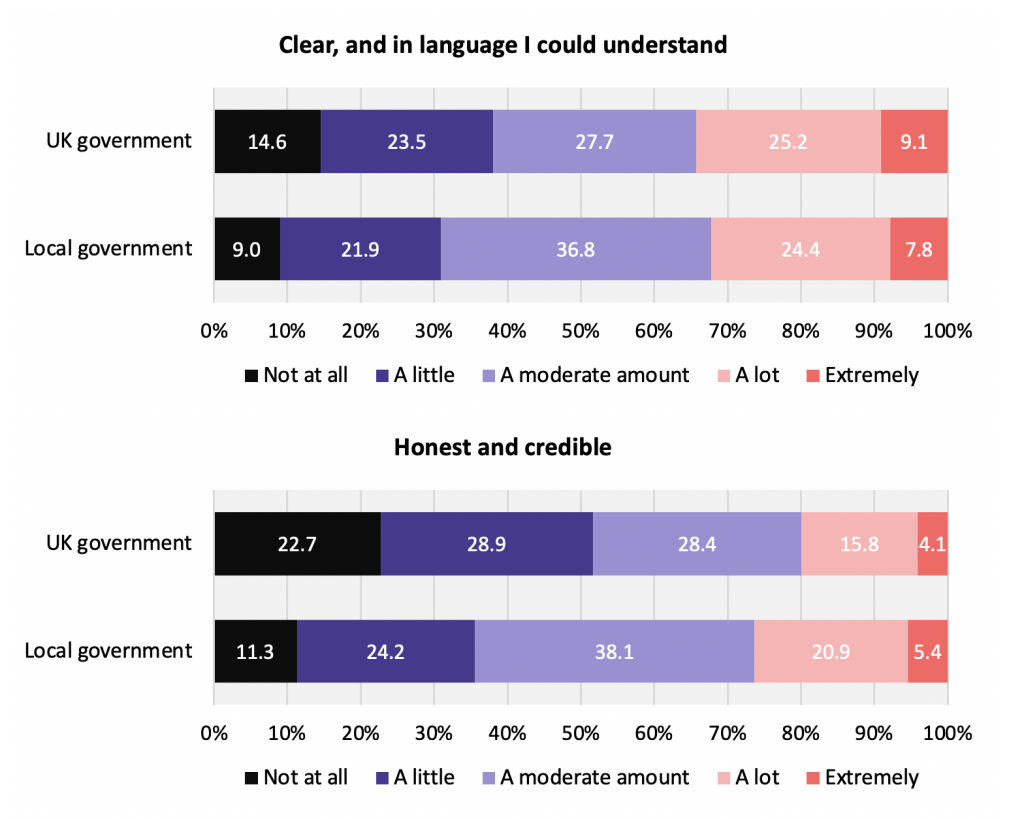

The latest findings from the Beyond Us and Them project is that people view the quality of UK government information about COVID-19 differently than that from other sources. We surveyed over 9000 people during June 2021 to examine perceptions of government and local government communication about COVID-19 over the last year. Ratings of the clarity of communication from both were similar (around a third thought it was not very clear or understandable, around a third thought it was clear and understandable), which suggests both need to improve clarity. There were important differences in perceptions of other aspects of UK versus local government communications.

About half of all respondents view UK government communications as low or very low in both credibility and honesty. Similar proportions believe it to lack empathy. 48% perceive that UK government communication does not meet the needs of their community, and only one in five thought it did meet these needs.

When judging communication from their local authorities, significantly fewer people rated it as low or very low, typically around one third on measures of credibility, honesty, empathy, and relevance, and just over a quarter of respondents (26%) rated the relevance to their community’s needs as high or very high.

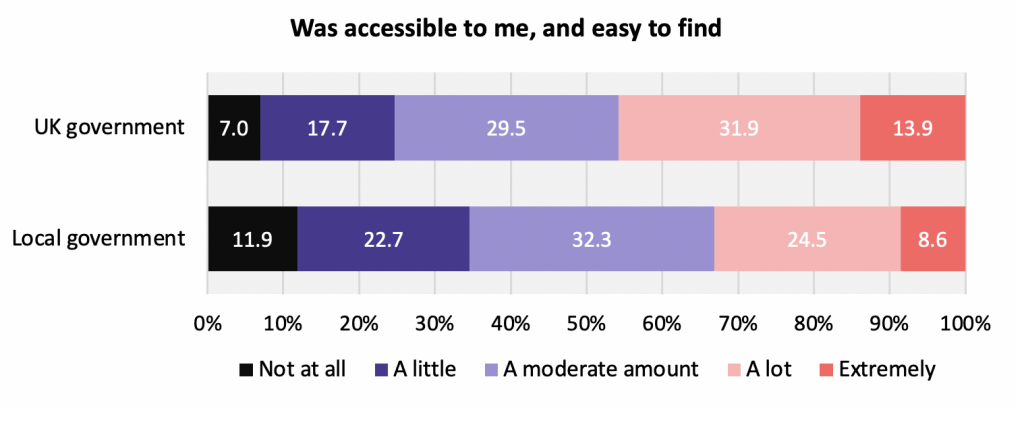

Figure 1: During the past year, I thought that communication about COVID-19 by [the UK / my local] government was…

From these findings we know two things. Quite a large proportion of people regard both UK and local government communication as lacking many of the characteristics that provide a foundation for trust, decisions and action. This perception is consistently stronger of UK government versus local government communications.

However, on measures of accessibility, only 24% found UK government information to be inaccessible, but 45% perceived it to be highly accessible and easy to find. In contrast 35% perceived local government information to be inaccessible and 33% perceived to be highly accessible. It may be that people use these surveys as an opportunity to show loyalty to their local area. We would then expect to see the UK vs local government differences emerging consistently across all localities. Another possibility is that people view the UK government as more remote, and less ‘personal’. If remoteness is the explanation we would also expect people in Wales and Scotland should report more positive perceptions of their local authority than of their devolved government.

Our evidence sheds light on both interpretations. First, we do find differences between different parts of the UK. Respondents in Wales, Scotland, within the Metropolitan Authorities of Greater London, Greater Manchester and the West of England viewed local government communications more positively. Those in the West Midlands Combined Authority and the county of Kent perceived less difference.

Second, in Scotland and Wales a smaller proportion rated their own government’s communications negatively on all measures, including accessibility (between 10% and 20%). The devolved governments appear to have hit the sweet spot, maximising perceptions of clarity, honesty, empathy, community relevance and accessibility relative to both UK government and local government communications.

There could be a number of reasons for this. The populations of Wales and Scotland may make it more feasible to communicate about the national picture and about differences within it. Leaders may more easily address factors that affect all communities in common, and those that differentiate them. People may also identify more readily with their nation than with the UK, or with their local authority area and gravitate towards national level communication as it has more meaning for their identity. In fact, people who identified more strongly with their local area rated local communications more positively, and those who identified more as ‘British’ rated UK government communications more positively, though we can’t be certain of the causal links.

It is possible respondents’ perceptions are in line with reality – that while UK and local government communications are sometimes complicated and difficult to understand, information from local authorities is more credible, trustworthy, empathetic and useful. Some local authorities do better than others, and the Welsh and Scottish governments are particularly accomplished, so may be able to share some of their methods or approaches to help others. Another possibility is that all the information and its quality is equally good, and we are witnessing social psychological biases, whereby people are psychologically orientated towards expressing more positive evaluations of more local sources. If either (or both) of these interpretations is correct it suggests that the most effective vehicles for messaging and behavioural influence are likely to be at the devolved or localised levels.

The UK government has done an astounding job at marshalling evidence, presenting it to the public, and sharing it with researchers. But it has been regularly criticised for then issuing confusing, late or inconsistent advice about how this information should translate to people’s behaviour. Yet it is hard to imagine how the UK government could feasibly recognise or respond to the very different local contexts. Scotland and Wales show that it is possible, in principle, to do better. In England, this could likely be achieved by strengthening the capacity of local government to act as purveyors and interpreters, as well as collectors, of information.

The implications go well beyond the pandemic. In a world facing many uncertainties in which wider social cooperation may be the key to resilience and growth, finding ways to convince people to change their behaviour becomes ever more pressing. A closer collaboration between local and higher levels of government may give the extra leverage in persuading people that ‘it is necessarily so’.

_____________________

Note: the above draws on findings from the latest report of the Beyond Us and Them Research Project, a partnership between Belong – The Cohesion and Integration Network and the University of Kent, funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

Dominic Abrams is a Professor of Social Psychology and the Director of the Centre for the Study of Group Processes in the School of Psychology at the University of Kent.

Jo Broadwood is Chief Executive of Belong – The Cohesion and Integration Network. Belong is a national charity and membership organisation with the aim of improving practice and policy for social cohesion.

Fanny Lalot is Research Associate in the School of Psychology at the University of Kent.

Kaya Davies Hayon is Research and Development Manager at Belong. She holds a PhD in cultural studies from the University of Manchester and worked in academia for a number of years before joining Belong.