Looking at the Department of Work and Pensions, Patrick Dunleavy and Leandro Carrera show that overall productivity levels failed to grow at all across two decades, despite massive capital investment, increased IT spend and several business process reorganizations. The dominance of a conservative organizational culture among senior public managers, plus constant policy churn, prevented any transition to delivering transactions or managing customer contacts in a modern, ‘digital era’ way.

Looking at the Department of Work and Pensions, Patrick Dunleavy and Leandro Carrera show that overall productivity levels failed to grow at all across two decades, despite massive capital investment, increased IT spend and several business process reorganizations. The dominance of a conservative organizational culture among senior public managers, plus constant policy churn, prevented any transition to delivering transactions or managing customer contacts in a modern, ‘digital era’ way.

The last Conservative government (1979-97) squeezed investment in Whitehall and public services, so that administrative systems became rickety and dangerously out of date. From 2000 the last Labour government spent billions of pounds on improving public services delivery and remodeling services. Neither strategy seems to have worked well.

We look at the productivity of the administrative machinery paying out £129 billion of social benefits to British citizens in 2008, almost an eighth of the country’s GDP. Since 2001 the social security system has been administered by one huge Whitehall department, the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP), bringing together paying 14 main welfare benefits with employment services (previously handled in separate departments).

To study DWP’s productivity as a whole we needed to cost-weight the different services being delivered, to get an overall index of outputs. To calculate overall productivity (called ‘total factor productivity’) we divide total weighted outputs by the amount of all factor inputs (i.e. labour, capital spending, contracting out costs) used to deliver them.

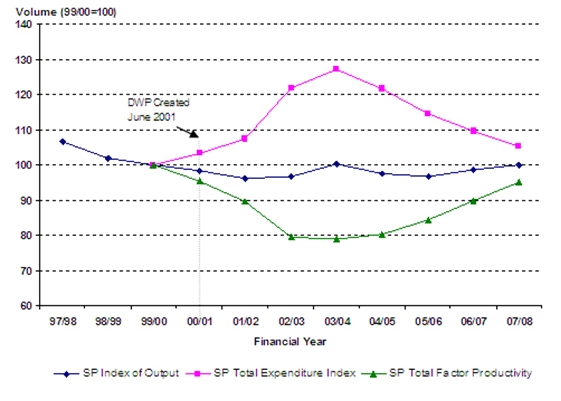

For the Labour period 1998-2008, we have the best outputs data, supplied by the Department itself. Our first chart shows that the overall DWP productivity declined from financial year 1999-2000 onwards, especially in 2001-2002 because of the huge organization costs of creating the new integrated DWP. Information technology and management consulting costs more than tripled from £94 million in 2001-2002 to £306 million two years later. Subsequently new benefits were introduced, especially Pensions Credit: its ‘teething problems’ created extra administration costs for some years.

Chart 1: Social security productivity (1998-2008)

From 2004-2005 onwards, however, as DWP settled down and new benefits processes were re-simplified, productivity gains were achieved in a fairly consistent pattern, bringing productivity levels almost back to where they started out by 2008.

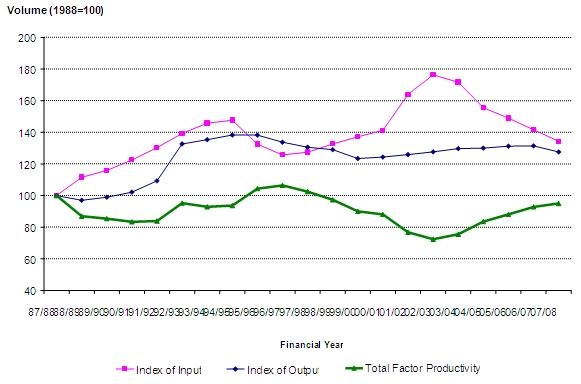

At this point Conservative-supporting readers may be feeling smug that our evidence confirms their view of the Labour government’s failings. So we wanted to look longer term also at the previous decade of Tory government. We have less perfect outputs data here, because we had to estimate productivity as only caseloads, and not claims, using publicly available data. Nevertheless Chart 2 below covers two decades of change in a consistent way using this data. And for the 1998-2008 period our two data sets show highly correlated trends.

Looking at the Tory government decade (1988-98) Chart 2 shows some temporary productivity growth, achieved by starving the administrative system of investment, pruning staff, and letting offices decay and IT systems get more dated. But these modest gains could not be sustained. By 1998, productivity in social security was exactly the same as it had been ten years earlier in 1988, and the system was more old-fashioned than ever.

Chart 2: Long-term estimates of changes social security productivity, since 1988

The net effect of the contrasting Tory and Labour strategies was to leave social security productivity almost unchanged. Across two decades of rapid technological progress, the delivery of welfare benefits got no more efficient.

Changes in social security administration

Several factors contributed to explaining this deeply depressing picture, including:

- A rapid succession of new laws (32 separate Acts in 20 years) created a constant top-down policy churn, which inhibited the ability to improve the systems in place. Bringing in new benefits and phasing out old ones always worsens productivity – although ministers invariably claim that it increases wider policy effectiveness.

- Despite just one change of government, in 1997, DWP Secretaries of State changed incessantly. There were 12 in ten years under Labour, a level that would cause regulatory investigations in any similarly large private firm.

- In 2001, Labour ministers merged the different agencies responsible for paying benefits and collecting contributions into a single Department of Work and Pensions. The new DWP tried to integrate labour market services with social security payments. It also began a massive transition from paper-based systems and face-to-face contacts in offices, towards using call centres.

- Spending on new information technology, consultants and PFI construction projects, all mushroomed during the Tony Blair government, partly catching up on a backlog of necessary work not done under the Tories, partly reflecting reorganizations.

Flat productivity and the cultural resistance to digital era changes

Yet none of the factors above explains the bulk of the stasis we have charted. Indeed new IT investments and simplified benefits policies should have cut costs. Instead, we need to look deeper, at the whole organisational culture of the UK’s social security system, which has always been extremely conservative about the adoption of new technologies. In the 1990s the then Department of Social Security ran 15 year IT investment programmes, that were outdated as soon as they were agreed. Even by the late 1990s, DSS provision for any form of Internet access was zero. The 2001 DWP decision to transition to using phone systems instead of paper processes was also adopting a twentieth century technology, at least 30 years late.

For much of the 1980s and ’90s DWP’s organisational culture was also dominated by the ‘new public management’ (NPM) doctrine, which focused on disaggregating large bureaucracies into smaller agencies (now put back together again); outsourcing to big IT contractors; and incentivising staff and contractors to deliver outcomes. DWP managers mostly ignored an alternative paradigm for public management in modern times, ‘digital era governance’ – which stresses re-integrating and joining-up services; remodelling internal structures around client needs; and digitalising all administrative operations.

Three main organisational culture problems inside DWP prevented top officials even considering a shift to digital-era governance. First, senior officials with little or no IT background themselves did not believe that the poorer households and individuals receiving welfare benefits would ever get Internet access. However, in 2008 they discovered to their surprise that 51 percent of DWP ‘clients’ were already online with broadband Internet access.

Second, for years top civil servants saw the web as merely a place for posting static billboards of information and had no conception of creating a more interactive Web experience. Third, internal organisational power over policy on IT was concentrated among officials (aged in their 40s and 50s) running the big-budget mainframe computer systems, who saw web processes as a financially trivial (and hence organisationally irrelevant) sideline.

Instead DWP administrators in 2001 began rebuilding most main benefits application processes around phone contacts and large call-centres. The only part of the department’s activities not affected was its labour market and job-search services, called Job Centre Plus (JCP), bought into DWP from another department. JCP continued to emphasize face-to-face contact with all working-age people receiving benefits, after an initial call-centre registration. But inside job centres clients to this day are completely unable to access the web, or to apply for jobs online: they can only passively view job vacancies on low-functionality ‘kiosks’. (To be fair, JCP’s labour market information services for the general public escaped the DWP pall, and did move onto websites: by 2007 they were hosting 40 percent of all vacancies in the UK and had enormous traffic volumes. But there was no counterpart to this in JCP’s transactions with unemployed people themselves).

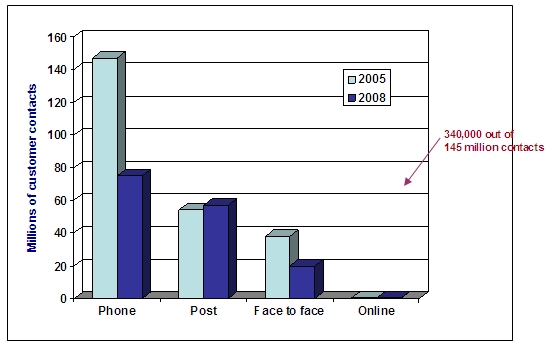

Even worse, shifting towards phone-based system at first only created a swamping avalanche of new phone calls, reaching crisis point by 2005, by when half of all calls were never picked up. The DWP top management determined to squeeze down phone calls again to reasonable levels. And as our third chart below shows they succeeded. Phone calls fell by over 40 percent in three years, which greatly stabilized the new business model and largely explains some of the late growth in productivity levels. Further cuts in face-to-face services also helped to prune costs.

Chart 3: The changing pattern of the DWP’s customer contacts, 2005 to 2008

Yet Chart 3 shows that DWP increased its use of paper-based forms sent by post in the late noughties. The department also developed no electronic transactions at all with any of its customer receiving benefits in the whole period from 1999 to 2005. E-transactions and e-contacts with customers increased barely at all, to just 340,000 per year, a fraction of one percent of the department’s annual 195 million contacts. The online services revolution left all the department’s core operations untouched.

Meanwhile many DWP customers were itching to use electronic services. During 2008 a few DWP officials put up a web-page allowing people to register online their interest in receiving Job Seekers’ Allowance. Usage quickly built up to more than 50,000 requests per month, catching DWP unawares. However, the department did not process any of the information received electronically. Instead after a delay (of up to three days), customers who registered electronically were rung back by the one of the department call centres and made to go through the normal phone-based registration process from scratch.

Learning from successful innovations

To see how contrasting progress was possible in developing electronic services, by 2009-10 three quarters of the over 9 million income tax self-assessment forms submitted by UK citizens came in online. This reflected a long learning process about the Internet by the tax agencies (now Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs) that started much earlier in 1999-2002.

Cashing out the impact of DWP’s neglect of Internet and web-based technologies, one rough estimate suggested that by neglecting online services and IT conservatism by 2009 the department was incurring up to £430 million of avoidable expenditure in Job Centre Plus alone. However, departmental civil servants strongly contest such estimates. They still argue that by retaining face-to-face contacts as part of its ‘active labour market’ interactions with working-age people, the DWP helped slow the growth of unemployment benefit claims in the 2008-2010 recession below forecast levels, greatly curbing the rise in unemployment payouts. This controversy cannot easily be resolved yet.

However, so far covering just the UK alone, studies by LSE Public Policy Group have documented cases of sustained productivity growth in tax collection and much more dramatic growth in government productivity in customs services and in the prison service. Understanding these variations over time is of great importance in understanding government efficiency in the UK and elsewhere. Why can some areas of government push through timely innovations, while others completely fail to do so?

This is an edited version of Leandro Carrera and Patrick Dunleavy, ‘Why Does Government Productivity Fail to Grow? New public management and UK social security’, in Esade Public blog, Number 22, January 2011.

PUBLIC is a leading European public administration and policy e-bulletin run by ESADE’s Institute of Public Governance and Management (IGDP) in Barcelona. It also publishes a Spanish version and a Catalan version of the article above.

Click here to respond to this article.

Please read our comments policy before posting.