The cap on tuition fees will rise to £9,000 in 2012. Gill Wyness reviews the evidence on the impact of past fee increases on young people’s decisions to go to university and finds that tuition fees, grants and loans have all had limited impacts on participation which is determined more by prior educational attainment. However, current analytical modelling cannot adequately control for the rate of increase set to be ushered in next year and questions remain as to whether debt-aversion will significantly put off bright young people from poor backgrounds.

The cap on tuition fees will rise to £9,000 in 2012. Gill Wyness reviews the evidence on the impact of past fee increases on young people’s decisions to go to university and finds that tuition fees, grants and loans have all had limited impacts on participation which is determined more by prior educational attainment. However, current analytical modelling cannot adequately control for the rate of increase set to be ushered in next year and questions remain as to whether debt-aversion will significantly put off bright young people from poor backgrounds.

The question of how to finance higher education has been on the agenda of successive UK governments since the 1960s. During that time, the country has moved from a situation where the taxpayer footed the entire bill for higher education to a system where graduates make a contribution to part of the cost of their education. This so-called ‘cost-sharing’ has always been a subject of controversy, with fears that it would lower participation, particularly among young people from poor backgrounds.

The recent announcement that the tuition fee cap – currently set at £3,300 a year – will be allowed to rise to £9,000 a year from 2012 has been met with opposition from a number of camps, including the media, the National Union of Students, parents and the students themselves who took to the streets in their masses. But what is the likely outcome of this almost threefold increase in fees?

Tuition fees were first introduced by the Labour government in the UK in 1998. They were payable upfront and means tested according to parental income, up to a maximum of £1,000 per year. Grants were subsequently abolished (having been gradually phased out over the 1990s), and replaced by maintenance loans.

A further major reform in 2006 saw upfront fees abolished and replaced by a deferred £3,000 fee – payable by all regardless of parental income but fully covered by a fee loan with quite generous terms. The loan is interest free and only payable after graduation (at a rate of 9% of earnings once the graduate is earning £15,000 or more), and all loans are written off after 25 years. Grants were also increased at this time (having been reintroduced in 2004) and maintenance loans extended.

Despite the fevered debate that has surrounded tuition fees, to date there has been very little investigation of their impact on participation. Our research used information on higher education finance and participation between 1992 and 2007– a period in which many reforms of higher education finance took place – to analyse the impact of tuition fees, grants and loans on participation.

Our results show that increases in tuition fees have a small but significant impact on participation of 3.3 percentage points per £1,000 increase. But the negative effect of fees can be offset by increases in loans and grants, which have small positive impacts on participation of around 2 percentage points each.

So what can this tell us about the forthcoming increase in tuition fees? Unfortunately, the answer is not straightforward. Our research looked at relatively small increases in fees – between zero and £1,000; and between £1,000 and £3,000 – while the reforms could see fees rise to as much as £9,000 per year.

It is unlikely that our results would still hold when applied to these substantial increases. But our results do indicate that fee increases have a negative effect on participation, contradicting recent media speculation that higher education is a ‘Giffen good’, which people paradoxically consume more of as the price rises.

The results also indicate that there is an important role for grants and loans in encouraging young people to go to university – so the government’s continued investment in the grant and loan system is welcome.

We have also looked at the likely distributional impact of the 2012 reforms on graduates, students, universities and the taxpayer. In this study, we used lifetime earnings simulations for future graduates created by researchers at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). These earnings profiles allow us to look at the impact of reforms on the distribution of graduates, by calculating graduates’ fee and maintenance loan repayment schedules under the new system.

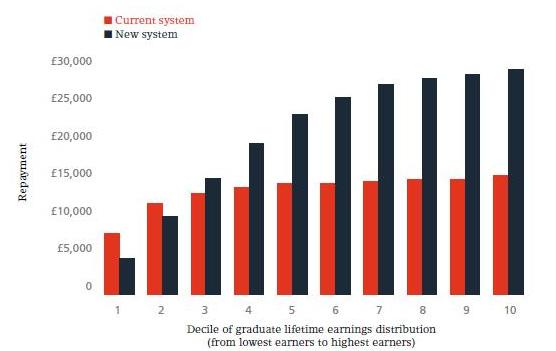

Figure 1: Maintenance and fee loan repayments

Figure 1 shows the lifetime fee and maintenance loan repayments of graduates from different parts of the income distribution, comparing repayments under the current system to repayments under the new system. In each case, we assume that graduates take out a fee and maintenance loan for each of the three years of their studies – with the fee loan assumed to be £7,500 under the new system.

We use the £7,500 figure for illustrative purposes, though given substantial cuts to the universities teaching budget, many universities would have to charge at least this amount to break even. Indeed, the majority of universities have chosen to charge close to £9,000 per year.

As Figure 1 shows, the new system is progressive: graduates who do well in the labour market – those at the top of the lifetime earnings distribution – repay significantly more over their lifetimes than those at the bottom of the earnings distribution.

In both the current and new system, the repayment arrangements protect low-earning graduates, many of whom will repay only a small proportion of their loan before it is written off. Low earning graduates will actually be better off under the new system, largely because the earnings threshold above which graduates have to start repaying their loans will be increased to £21,000 under the new system.

But will young people bear this in mind when deciding whether or not to participate in higher education? Or will the prospect of graduating from university with fee and maintenance loan debts of as much as £40,000 dissuade bright young people, particularly those from poor backgrounds who may be particularly debt-averse?

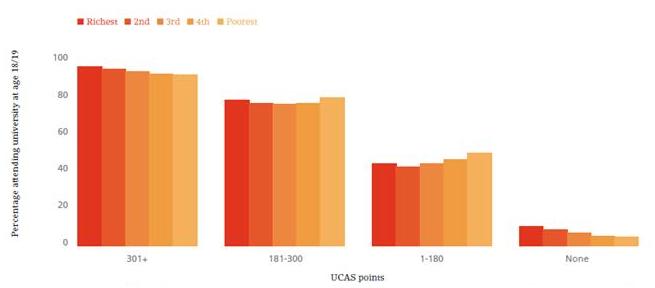

An IFS study of participation in higher education by young people from different backgrounds suggests not. Figure 2 shows the proportion of young people who participate in university, comparing those from different backgrounds (measured by socio-economic position) but with the same A-level scores.

Figure 2: University participation by socio-economic position and UCAS points achieved (2004/05)

Young people with 301 or more UCAS points (three good A-levels) have a high probability of going to university, regardless of their background. In 2004/05, roughly nine out of ten young people with those results participated in higher education at age 18/19, with those from poorer backgrounds just as likely to participate as those from richer backgrounds. Meanwhile, young people with no UCAS points have a very low probability of going to university regardless of their socio-economic background.

This research clearly shows that while tuition fees, grants and loans may have a small impact on participation, the major factor in whether young people will go to university is not the fees that they face, but their prior educational attainment.

This is where background does matter since young people from poor backgrounds are extremely unlikely to achieve the necessary A-level results to obtain a place at university. Only 3% of young people from the poorest backgrounds achieved 301 or more UCAS points in 2004 compared with 25% of young people from the richest backgrounds.

Of course, it may be that young people have decided not to go to university anyway, perhaps put off by tuition fees, and therefore put less effort into achieving high A-level scores. Nevertheless, the evidence to date strongly suggests that higher education finance has had a limited role to play in participation. But given the substantial increase in tuition fees from 2012, we cannot be confident that this will continue to be the case.

This article first appeared in the CentrePiece magazine Volume 16, Issue 1, Summer 2011, which is now available online.

Please read our comments policy before posting