Rebecca Montacute writes that much of Boris Johnson’s reshuffled cabinet comes from similar backgrounds, and has gone through the same institutions, bringing this way a very limited set of life experiences to the table.

Rebecca Montacute writes that much of Boris Johnson’s reshuffled cabinet comes from similar backgrounds, and has gone through the same institutions, bringing this way a very limited set of life experiences to the table.

In previous reshuffles, Boris Johnson has made a point to highlight the ‘diversity’ of his cabinet, which he called a ‘cabinet for modern Britain’. However, while his cabinets have had a record number of ministers from ethnic minority backgrounds, they still remain very unrepresentative of the country on other measures, including by socio-economic background.

What are the educational backgrounds of Johnson’s new cabinet?

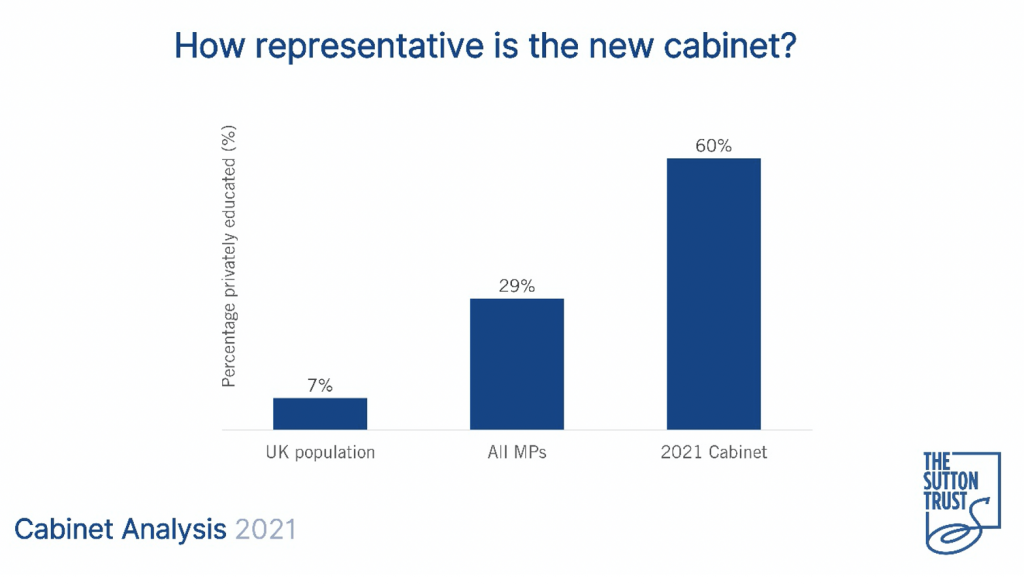

60% of Boris Johnson’s new cabinet attended an independent school, a small decrease from 2020 when the figure was 65%, but still far higher than the general population, of whom only about 7% go to fee-paying schools. Boris Johnson, The proportion of privately educated ministers is also higher than the parliamentary Conservative party overall, of which 45% attended a private school. Many ministers attended a very narrow set of elite universities. Just under half (47%) attended Oxford or Cambridge, while just over a quarter (27%) attended an independent school followed by Oxbridge, giving the new cabinet at large a very similar set of educational experiences.

Yet who has a seat at the top table really matters. Ministers make decisions which affect all of us. If they largely come from similar backgrounds, and go through the same institutions, they will collectively have a very limited set of life experiences to bring to the table. Without a diversity of perspectives, even with the best intentions, a government can miss important issues, or just not see them as a priority.

A good example is how prominently top universities feature in our national debate. Scrutiny on access to these institutions is important, but the attention they receive is out of all proportion to the small proportion of the population they educate. Even with the government’s welcome focus on technical and vocational routes as part of its levelling up agenda, with a cabinet so far removed from this part of the education system themselves, how well they will succeed in truly moving away from a focus on higher education and universities remains an open question.

Politicians are ultimately responsible for education policy, including the state school system. But many of the Cabinet do not have experience of that system themselves. And individually, schools also play a pivotal role in the opportunities available to students, from the quality of teachers that students have access to, the careers advice they receive, the networks they form, through to the range of extracurricular activities they can take part in. And while private school attendance is not a perfect measure of socio-economic background, it does serve as a good proxy. The vast majority of students at independent schools receive no or very little financial support in the form of bursaries or scholarships.

How does the new cabinet compare to previous cabinets?

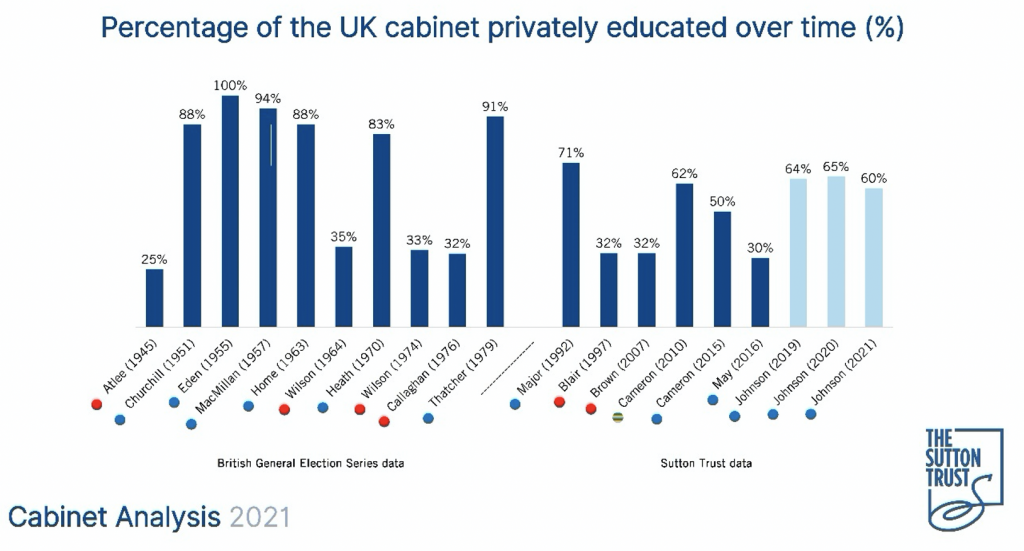

The privately educated proportion of Johnson’s cabinets have been considerably higher than Theresa May’s in 2016 (30%) but have only been slightly higher than David Cameron’s in 2015 (50%) and similar to the Coalition’s cabinet in 2010 (62%). Boris Johnson has nevertheless reversed a downward trend which was seen in Conservative governments since the 1990s, with gradual falls across the last four Conservative administrations before Johnson took power. Ministers in the current cabinet are though still less likely to have been to an independent school than several other Conservative governments, including John Major’s (71%), Margaret Thatcher’s (91%), and Ted Heath’s (83%).

How can socio-economic diversity in the top professions be increased?

Socio-economic inequality starts early, with children from poorer homes already 11 months behind their better-off peers when they first start at school. Children from lower income backgrounds then face barriers throughout their time in school, through to further or higher education, and onto the workplace. The Sutton Trust’s research looks into these barriers at every level of education, and includes a guide for employers on what they can do to open up access to the world of work. Our research includes recommendations for government, universities, schools, employers and wider society to tackle these inequalities, from how to improve access to and the quality of early years education, to the best ways to improve access to university.

Looking specifically at access to parliament, we have previously highlighted financial barriers for would be MPs, including unpaid internships in parliament, which can be an important first step towards a parliamentary career. Our research found that a third of staffers working in Westminster (the entry-level to political careers for many) have previously worked for an MP unpaid. And while Boris Johnson has previously given his support to the call to ban unpaid internships, his government has not acted on this issue.

Any child born today in the UK should have an fair shot at becoming a cabinet minister, regardless of the family they come from. But the latest reshuffle shows we remain far away from that today.

__________________

Rebecca Montacute is Research and Policy Manager at The Sutton Trust.

Rebecca Montacute is Research and Policy Manager at The Sutton Trust.

Photo by Vadim Sherbakov on Unsplash.