Anne Lise Ellingsæter and Ragnhild Steen Jensen explain how society’s perceptions of the nature and desirability of women’s part-time work are changing. They draw evidence from Norway and consider the implications for other countries.

Anne Lise Ellingsæter and Ragnhild Steen Jensen explain how society’s perceptions of the nature and desirability of women’s part-time work are changing. They draw evidence from Norway and consider the implications for other countries.

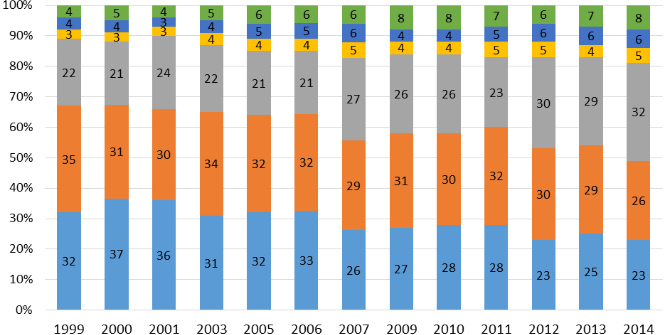

Part-time work is generally associated with women and as being a way of helping mothers balance work and family life. However, the role of part-time work in women’s labour market adaptations differs across Europe. In Scandinavia, the previously high levels of part-time employment among women are declining, and the link between motherhood and part-time work is disappearing. The long passage of time since women in great numbers entered the labour market, many in part-time jobs, provides an opportunity to investigate how society’s perceptions of the nature and the desirability of women’s part-time work may change.

Our study is based on ten Norwegian government advisory commission reports, published between 1978 and 2016. Such reports play a vital role in formulating public policy, and are a core element of the consensual Nordic model of government. Spanning four decades, the study reveals profound changes in perceptions: from being a strategy for increasing women’s economic independence and individual choice, part-time work has become undesirable, whereas full-time work for all women is promoted.

A changing national context has transformed perceptions of part-time work and the ‘woman worker’. The long-term normative goal of gender equality has merged with the all-encompassing goal of welfare state sustainability. The earlier perception of part-time work/reduced working hours as a solution to job sharing was replaced by part-time work as a barrier to mobilising the labour needed especially in the female dominated care sector – women’s voluntary part-time work was recognised as a labour reserve. Choice weakened as a normative value regarding working time, while citizens’ duty to work and economic self-sufficiency increasingly pushed attention towards full-time work.

The ‘work line’ – the goal that everybody must be able to provide for themselves – was not explicitly referred to in the commission reports but figured in the background as a normative consensus. Perceptions of the causes of women’s part-time work became more complex: the individual woman’s need to reconcile employment and childcare lost traction as the main explanation.

Ideational change in the ‘gender contract’ – the shape of the gender order under historical specific circumstances – interacted with change at the institutional and the individual level. The gender contract at the ideational level is moving away from the compromise involving a ‘normalisation’ of women’s part-time work as part of a modified male breadwinner contract, towards a new gender-neutral adult worker contract. Both institutional care reforms and a more egalitarian division of labour in families have facilitated this shift. However, change in institutions and parents’ practices did not occur in tandem with ideational change, but rather preceded and conditioned new ideas about women’s part-time work.

The conception of the ‘woman worker’ was transformed through a process of degendering. When the woman worker was considered an encumbered worker, part-time work was acknowledged as reconciling women’s roles as caregivers and wageworkers. But the institutional context of care work changed fundamentally after the childcare reforms in the 1990s and 2000s – by redistributing care work.

Institutional support for fathers’ care work changed traditional conceptions of both men and women as parents. The father quota – earmarked parental leave for fathers – redistributed childcare within the family. Universal childcare provision (in terms of rights and access) transferred parts of the care work from the family to the state. Nine out of ten children aged 1-5 years old are enrolled in childcare services. Almost all mothers are employed and the majority works full-time. All this changed the basis of the conception of the female worker as a caregiver, facilitating a break with the traditional conception of women as encumbered workers. In principle, women and men became (more) equal as workers. This created a new foundation for considering women’s employment as not only a right, but as an obligation, as is the case for men. This is likely to have been further strengthened by changes in the general perception of ‘the worker’ from a democratic citizen who should contribute also to wider society, to a narrower economic actor who should contribute to the national economy and thus the sustainability of the welfare state.

In contrast to the Scandinavian adult worker model, the European Union promotes part-time work. The rapid growth of part-time work during the 1980s and 1990s revealed disadvantages in terms of wages, career advancement and the like, but according to the OECD this ‘clashed with a reality’ where the vast majority of women work part-time on a voluntary basis. As a result, governments moved away from viewing part-time as a form of ‘labour market dualism’ and sought to promote it as a way to mobilise groups with traditionally low labour market participation, including mothers with young children. This perception of women’s part-time work still fits the description articulated two decades ago: a ‘universal modification’ to the existing sexual division of labour, a particular form of gender contract or compromise.

Considering future prospects of part-time work, scholars in the late 1990s suggested demarginalisation and degendering of part-time work for this ‘universal’ of women’s employment to be broken. Our study exposes an alternative pathway: the degendering of full-time work. Economic and demographic conditions shaping the national demand for labour emerge as a driving force in the history of the politicisation of women’s work. However, ideas influence framing of policy problems and solutions, including ideas with regard to which women and when in their life course they are considered workers. Mobilisation of labour is a crucial policy concern in contemporary Europe, where policies maximising women’s labour force participation are directed at mobilising encumbered women outside the labour market into part-time work. By contrast, the Norwegian case shows that when institutional childcare reforms have eradicated a historical barrier to mothers’ employment, women’s voluntary part-time work may well emerge as the next reserve to be tapped.

___________

Anne Lise Ellingsæter is Professor in the department of sociology and human geography at the University of Oslo.

Anne Lise Ellingsæter is Professor in the department of sociology and human geography at the University of Oslo.

Ragnhild Steen Jensen is a researcher at the Fafo Institute for Labour and Social Research, Norway.

Ragnhild Steen Jensen is a researcher at the Fafo Institute for Labour and Social Research, Norway.