Evidence suggests that despite significant progress in recent years, discrimination against sexual minorities remains widespread among UK society. Rather than pointing the finger elsewhere, argues Stuart J Turnbull-Dugarte, the UK must come to terms with and address the intolerance that continues to exist at home.

It’s been close to 10 years since David Cameron and Nick Clegg’s Conservative-Liberal Democratic coalition government took the plunge and brought legislation forward to legalise equal marriage in England and Wales. At the time, opposition towards advancing LGBT+ rights in the UK was still commonplace, particularly among some Conservative voters and Tory backbenchers.

Fast-forward a few years, and the UK’s social tolerance towards LGBT+ individuals appears to have changed dramatically. Outspoken opposition to homosexuality is an untenable political position for a mainstream party leader, LGBT+ representation in the Commons is enjoying a record high, LGBT+ inclusive education has been protected in law, and pundits from across the UK were largely unanimous in their criticism of the treatment of LGBT+ individuals in Qatar when the country hosted the 2022 FIFA World Cup.

Is Britain now a country free of prejudices towards LGBT+ individuals?

This aesthetic transformation presents Britain as a country where intolerance towards LGBT+ individuals is no longer tolerated. Self-reported tolerance levels of homosexuality and persons who identify as LGBT+ support this: regardless of partisan attachments, more than 90 per cent of British people agree, “homosexuals should be free to live as they wish”. Is Britain a country free of its own prejudices towards LGBT+ individuals? Last autumn’s World Cup generated much attention towards the failures of Qatar, but should we instead be looking closer to home?

The difficulty of gathering accurate data

Assessing the real presence of homonegativity is hard. Social desirability means that individuals often mask their true preferences in response to what they consider to be socially acceptable or not. An individual, for example, may well harbour xenophobic or homophobic attitudes, but, because of pressures set by societal expectations and norms about what is acceptable, opt to hide these prejudiced views when asked outright for their views on migrants or on ethnic or sexual minorities.

Experiments can help with these problems. So too can moving away from asking individuals about their specific views on LGB(T+) individuals, but rather assessing whether they would provide equal access to certain provisions independently of sexuality/gender identity. This is the approach I undertook in a recent study which looked at views on surrogacy.

Individuals often mask their true preferences in response to what they consider to be socially acceptable or not.

Relying on a surrogate to help start a family is becoming increasingly common and several widely-known heterosexual and homosexual celebrities, such as the Star Wars creator George Lucas, have relied on the process. Surrogacy is also one of the limited means through which same-sex couples can have biological children of their own, making it a sought-after means of starting a family among this demographic. But is the process regarded as equally acceptable for Jack and Bill as it is for Jack and Jill?

Examining the evidence

To test if people’s concrete preferences for surrogacy are shaped by homonegative biases, I designed an experiment that could mitigate the risks involved in asking respondents for their views directly. Essentially, the experiment involved asking a representative sample of citizens if they would support the use of surrogacy for different couples. The couples I asked about varied in terms of whether they were well-known celebrities or fictional everyday couples. The celebrity examples I presented were the Olympic diver Tom Daley and his partner (a same-sex couple) and actress Sarah Jessica Parker and her partner (an opposite-sex couple). Both Daley and Parker have relied on surrogacy in the past.

Support for the use of surrogacy, whilst high, is significantly shaped by respondents’ biases against same-sex couples.

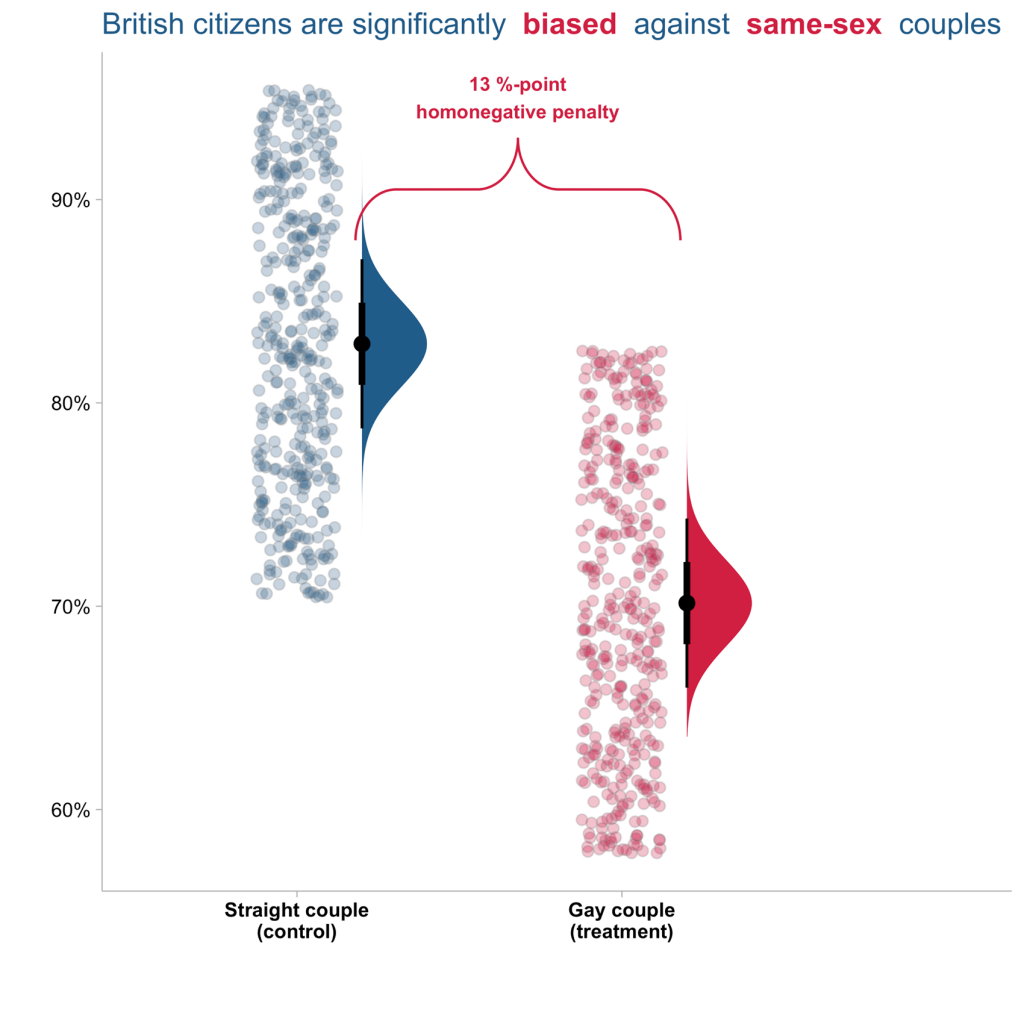

The results, summarised in the figure below, paint a negative picture of LGBT+ acceptance in Britain. Support for the use of surrogacy, whilst high, is significantly shaped by respondents’ biases against same-sex couples. Comparing the levels of support for the policy between individuals presented with one of the heterosexual opposite-sex couples (control condition in the experiment) and those presented with one the homosexual same-sex couples (treatment condition in the experiment), we can observe that the latter receives much lower support.

The battle for acceptance is far from won

As explored in the detailed report of the experiment, the sizeable discriminatory penalty is present among both conventionally left-wing and right-wing voters. While the bias among right-wing voters is larger, at around 20 points, even left-wing voters exhibit a sizeable 10-point homonegative prejudice that penalises same-sex couples.

In the weeks leading up to World Cup in Qatar, much has been made of the discriminatory treatment of LGBT+ individuals in the country. Whilst social tolerance towards homosexuality and respect for the rights of other sexual or gender minorities are obviously far greater in Britain than in Qatar, the results presented in this study signal that the presence and consequences of discriminatory homonegativity biases in the UK are far from marginal. Although individuals may not be inclined to publicly admit it, latent discriminatory biases against sexual minorities are, unfortunately, very much alive, and well in Britain today.

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work, available open access, in the Journal of European Public Policy

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by Mercedes Mehling via unsplash