Politicians, journalists, and think tanks frequently try to put a number on just how much welfare recipients receive in benefits – often massaging the figures in the process. But do exaggerated claims about benefit amounts really change anybody’s mind about welfare overall? New research by Carsten Jensen and Anthony Kevins confirms that they indeed do.

Politicians, journalists, and think tanks frequently try to put a number on just how much welfare recipients receive in benefits – often massaging the figures in the process. But do exaggerated claims about benefit amounts really change anybody’s mind about welfare overall? New research by Carsten Jensen and Anthony Kevins confirms that they indeed do.

If you follow politics, or even just glance at newspaper headlines from time to time, you’ve probably come across quite a few claims about how much welfare recipients can “rake in” from benefits. To take just one well-known example, former Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne recounted the shock he felt when, after taking office, he realised that some people were receiving “£100,000 a year in benefit”. Given how widely the exact amount of these figures varies, it seems clear that such numbers can easily be massaged or cherry-picked to align with prior ideological convictions. Presumably, the goal of propagating these sorts of welfare myths is to convince others that benefits are more generous than they should be, often by drawing comparisons to the income levels of those working in low-wage employment. But do claims like these actually have any effect on people, or have we all just made up our minds in advance?

In our new study, funded by Aarhus University’s Department of Political Science and recently published in Political Studies, we find that inflated claims about benefit levels may indeed have a negative impact on attitudes toward benefit generosity.

Using data from an original survey experiment that we conducted on approximately 2,000 Britons, we set out to answer two questions. First, we wanted to know if the size of the asserted benefit income matters. We therefore presented respondents with a benefit income level for the “typical family on welfare”, supposedly based on data from the Office for National Statistics – but we varied the stated figure, which ranged from £9,000 to £29,000 (in intervals of £5,000).

Second, because past research suggests that citizens may not be particularly familiar with the income distribution, we also examined whether adding in information about minimum wage income would shape responses to asserted figures. To that end, half of our survey respondents also received information about the take-home income of a typical family working at minimum wage (set at £19,000 in the text), presented alongside an asserted benefit income of a family on welfare.

Inflated figures, inflated opposition

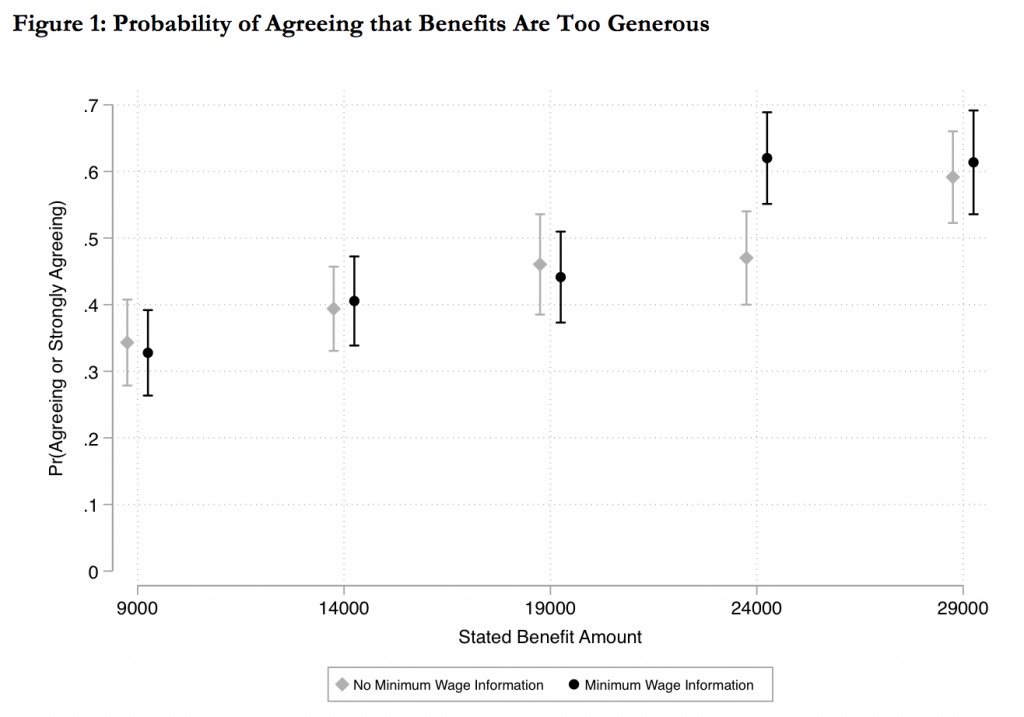

Results of our survey experiment suggest that when the asserted level of benefit income is high, there is a greater chance that an individual will think benefit levels are too generous. At the same time, however, we find that information about the minimum wage income level only shapes reactions to these figures in one instance: when the asserted benefit level is modestly higher than the stated minimum wage income.

Note: the stated benefit amount is given in pounds sterling.

Note: the stated benefit amount is given in pounds sterling.

Figure 1 summarises our overall findings, illustrating the likelihood that an individual will agree that benefits are too generous, broken down by the size of the asserted benefit income presented to a respondent, as well as whether or not information about the minimum wage income was included in the same text. As we can see in the figure, there are only limited differences between the responses of those individuals who saw either the £9,000, £14,000, or £19,000 claims.

Although there is a meaningful difference between respondents who saw the £9,000 figure and those who saw the £19,000 one, neither group is distinguishable from the one that was presented the £14,000 figure. The effects are starker once we enter the £20,000 range, however: on the whole, respondents presented with the £29,000 figure were more likely to feel that benefits were too generous, regardless of whether or not they also received information about the minimum wage income; yet those who saw the £24,000 figure felt the same way only when minimum wage income information was also included.

Similar effects for egalitarians and anti-egalitarians

The size of the asserted benefit level does seem to matter, then. It could be, however, that these effects are driven by specific types of citizens. There’s probably good reason to assume, for example, that people with pro- or anti-welfare state tendencies might react differently to these claims, as may those with high or low levels of knowledge about politics. Our study explores these possibilities as well, ultimately finding that: (1) although egalitarians and anti-egalitarians start from different baseline attitudes, respondents generally react to increasingly large asserted benefit levels in surprisingly similar ways; and (2) the difference between responses to the £24,000 figure with and without minimum wage income information appears to be driven by those respondents with low levels of political knowledge. As a result, it seems that while increasing the asserted benefit level has a relatively widespread (gradual) impact, the importance of minimum wage information is limited to those with less pre-existing knowledge of politics.

Potential policy implications

Massaging the numbers to come up with headline-worthy levels of benefit income thus seems to be a potentially fruitful strategy for opponents of the welfare state. These findings are all the more important given their possible policy implications: to the extent that these sorts of claims can shape public opinion, they may serve to shore up support for welfare cuts. Policies like the benefits cap – for better or for worse – seem to be a particularly likely end result. So, proponents of an expansive welfare state will want to pay particular attention to these sorts of number-based narratives, breaking down asserted figures and proposing their own in return.

___________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in Political Studies.

Carsten Jensen is Professor in the Department of Political Science at Aarhus University. His research is focused on the causes and consequences of redistributive politics in advanced western democracies, as well as democratic representation more broadly. His work has been published in journals such as the American Journal of Political Science, the British Journal of Political Science, and Comparative Political Studies.

Carsten Jensen is Professor in the Department of Political Science at Aarhus University. His research is focused on the causes and consequences of redistributive politics in advanced western democracies, as well as democratic representation more broadly. His work has been published in journals such as the American Journal of Political Science, the British Journal of Political Science, and Comparative Political Studies.

Anthony Kevins is a Marie Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at Utrecht University’s School of Governance. His research centres around the reciprocal relationship between public opinion and social policy reform, and his work has been published in journals such as Socio-Economic Review, the Journal of European Social Policy, and the European Political Science Review. You can read more about his research on his website, which also includes non-paywalled, open-access copies of all of his published articles.

Anthony Kevins is a Marie Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at Utrecht University’s School of Governance. His research centres around the reciprocal relationship between public opinion and social policy reform, and his work has been published in journals such as Socio-Economic Review, the Journal of European Social Policy, and the European Political Science Review. You can read more about his research on his website, which also includes non-paywalled, open-access copies of all of his published articles.

1 Comments