For over two years, a research team at the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) has been studying the likely impact of the UK leaving the European Union. Their latest report focuses on the impact of ‘Brexit’ through changing trade patterns. Under ‘optimistic’ assumptions, there is a fall in national income of 1.3 per cent (about £850 per household). Under ‘pessimistic’ assumptions, this doubles to 2.6 per cent. When the dynamic effects of higher trade costs on productivity are included, the cost may rise to between 6.3 per cent and 9.5 per cent in the long run.

There are many issues that will weigh in the minds of voters in the run up to the 23rd June EU referendum. Many people feel that they are oppressed by a remote, undemocratic super-state that can over-rule British laws. Others believe that the EU promotes better co-operation between communities that were at war for centuries. These views often stem from deeply held political and moral beliefs.

Economics can make a small contribution to the debate by considering what might be the material costs and benefits of leaving the EU. If there are economic benefits, then for Eurosceptics it’s a win-win. On the other hand, if there are economic costs to Brexit, then even a die-hard Leaver must consider whether the price is too high. Some might be prepared to pay any cost, for them it is ‘death before enslavement’. To most people however, it’s not so all-or-nothing. They will look at the likely costs and benefits, and this will help inform their decision.

Figuring out the economic costs and benefits of Brexit

An obvious benefit of Brexit is that the UK will not have to send so much money to Brussels. On net this is around 0.31 per cent of our national income. An equally obvious cost of Brexit is that trade between the UK and EU will be lower if the UK leaves than if it stays. The degree to which trade costs will be higher outside the EU is a big question. But it’s a fact that even when countries have comprehensive trade deals (such as Norway’s deal in the European Economic Area, EEA) there are still non-tariff barriers due to regulatory differences, border checks, rule-of-origin requirements and anti-dumping actions. This is why even Norway has been found to have less trade with the EU than would be expected from such a deep level of integration.

There are a rich menu of economic models to analyse the impact of trade arrangements, but it turns out that most of them have a pretty similar structure when it comes to thinking about welfare gains. Our work develops a state-of-the-art (but bog-standard) trade model plus industry-level data on exports and imports covering all sectors of the economy in every country in the world. This, plus an estimate of how trade responds to costs, enables us to figure out how trade patterns and living standards will change when trade costs (tariff and non-tariff barriers) change after Brexit.

Since it is hard to know precisely how trade costs will change after Brexit, we look at two stark scenarios. An ‘optimistic’ scenario is that the UK swiftly strikes a deal so that it gets deep access to the EU single market, like Norway. A ‘pessimistic’ scenario is that the UK is unwilling to accept the free movement of labour and the associated regulations that are part of the ‘access price’ to the single market and so will prefer the usual EU external tariffs. Trade will fall by more in this case.

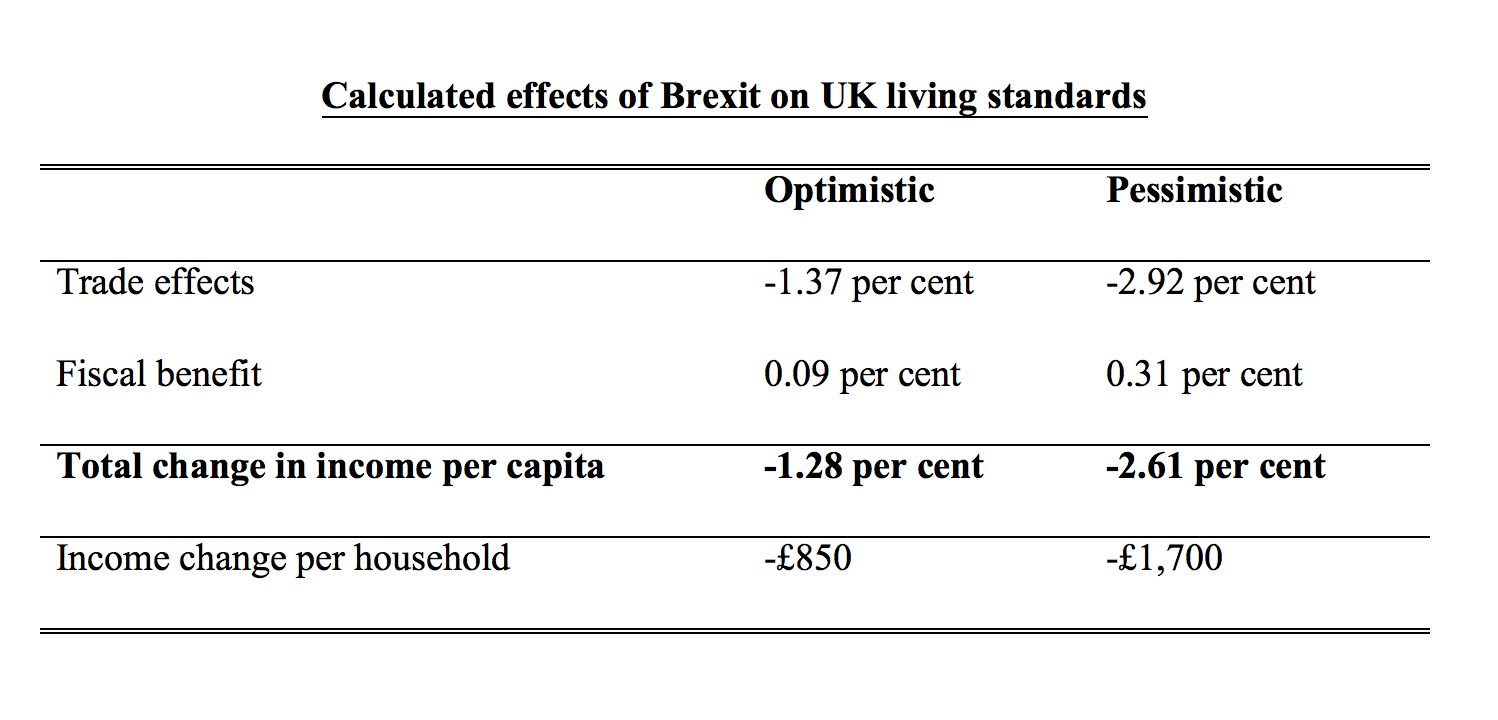

The table shows the results of our analysis. There is a drop in income per person of 1.3 per cent in the optimistic case, which doubles to 2.6 per cent in the pessimistic case. This translates to a fall of between £850 and £1,700 per UK household.

Source: CEP calculations (Technical details available here). Income based on allocating GDP loss per household. For example, 1.3 per cent of UK GDP is £23 billion and there are about 27 million households.

Source: CEP calculations (Technical details available here). Income based on allocating GDP loss per household. For example, 1.3 per cent of UK GDP is £23 billion and there are about 27 million households.

Is the pessimistic scenario too optimistic? Probably yes

The calculations we make are very narrow. They assume away any positive effects that trade may have on productivity through more competition, innovation, foreign investment and migration. We also abstract away from the economic damage induced by the policy uncertainty in the very difficult negotiating period following a Brexit vote. Negotiations over new trade agreements could stretch over many years.

An alternative ‘back of the envelope’ way to estimate the effects of Brexit is to look at what actually happens when countries joined the EU compared with being in free trade areas like the European Free Trade Area or EEA. The trade effects are big – a jump of a quarter or more. Combining this with estimates of the impact of trade on GDP from real falls in trade costs leads to an implied fall of UK national income of between 6.3 per cent and 9.5 per cent. Interestingly, this is squarely within the range of values that others have estimated have been the historical benefits of the UK joining the EU of around 8 per cent to 10 per cent.

This tripling of the costs of trade loss are also consistent with the literature of economic research comparing the actual benefits of trade liberalisation (big) with those predicted from static models like those presented here (much smaller). Naturally, UK trade with the EU does not disappear in any scenario – there remains a ‘trade deal’ in all cases. It is simply that there is less than it would have been had the UK remained a member.

It makes little sense to point to a decline in the EU’s share of total UK trade over the last decade as evidence that the single market has ‘failed to reduce trade costs.’ This decade has witnessed the rapid growth of Asian trade powerhouses as well as the worst global economic crisis since the Great Depression. Britain’s trade with Europe has increased since 2000, it’s just that trade with China has increased much faster.

Is the optimistic case too pessimistic?

How could things turn out better? First, could the UK negotiate a sweetheart deal much better than Norway or Switzerland have managed? This seems unlikely. About half of the UK’s exports go to the EU, whereas only 10 per cent of the EU’s exports are destined for the UK, so the bargaining power is lopsided. What’s more, the EU will not want to be seen to be offering generous rewards for leaving as this will encourage other members to try the same trick. And in addition, all this assumes that everyone is behaving reasonably and rationally – unfortunately divorces tend to be much messier. Kicking the EU when it is undergoing a major refugee crisis and a long-running monetary crisis might provoke some very grumpy outcomes.

Second, could the UK strike better trade deals with non-EU countries like the United States, China and India than with the EU? Although the UK will not have to compromise with other EU members when doing such deals, it cannot offer access to the biggest single market in the world as the EU does (UK GDP is under a fifth of the size of the single market). The EU is in the final stages of negotiation with the United States and Japan on deals estimated to raise GDP by 0.6 per cent. If the UK cannot replicate these deals (and the United States has stated it is not interested in a UK-only deal), this will be a further income loss on top of the estimates here.

Finally, what about the promised bonfire of red-tape when we leave the EU? Being outside the EU would enable the UK in principle to jettison some irritating regulations. But it’s worth bearing in mind that being in the EU has not stopped the UK from having one of the most flexible product and labour markets in the OECD (behind only the United States and sometimes Canada).

The real question is whether much better regulation will really be forthcoming after Brexit. We often hear by Eurosceptics that “the 100 most burdensome EU regulations have been estimated to impose annual costs of £33.3 billion”. But what they neglect to mention is that the government impact assessments they cite also estimate that the same 100 regulations bring benefits to Britain of £58.6 billion per year! It’s been argued that by getting rid only of those regulations where costs are deemed to outweigh benefits, 0.9 per cent of GDP could be saved. About half of this is estimated to come from the Renewable Energy Strategy and the Working Time Directive. It’s unclear that tearing up these environmental and employment protections will be politically feasible or really as economically beneficial in the long run as the impact assessments find.

Is Brexit a price worth paying?

Many people may decide that knocking a grand or two off their salary or pension is worthwhile to get Brussels off their backs. Some – though probably fewer – might even say the same if the bill rises to over £6,000 a year. These are reasonable positions and every voter will make up their own mind over the price they are willing to pay. But those who say that leaving the EU is a win-win because Britons will both feel more free and become a lot richer are not being candid about the evidence. The standard trade models given here, calculations from trade and income differences of being in and out of the EU and also historical assessments show a consistent picture – Brexit will cost. The only question is ‘exactly how much’?

Please note: This articles summarises the study ‘The consequences of Brexit for UK trade and living standards’. The report has been attacked by Vote Leave. First, they say the report is EU funded. This is untrue: our work is funded by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (as a whole, CEP receives less than 5 per cent of its funding from the EU). Second, they say the authors lack credibility because we also supported Euro entry. This too is untrue: Professor John Van Reenen, who has been CEP Director since 2003, has never supported the UK joining the Euro. Vote Leave’s other points were all addressed by the original report and are amplified in the above piece.

About the Authors

Swati Dhingra is a Lecturer in Economics at the LSE.

Swati Dhingra is a Lecturer in Economics at the LSE.

Gianmarco Ottaviano is Professor of Economics at the LSE.

Gianmarco Ottaviano is Professor of Economics at the LSE.

Thomas Sampson is an Assistant Professor in Economics at the LSE.

Thomas Sampson is an Assistant Professor in Economics at the LSE.

John Van Reenen is Professor of Economics at the LSE and Director of the CEP.

John Van Reenen is Professor of Economics at the LSE and Director of the CEP.

Globalist Soros also said the UK economy would suffer because the ‘currency would devalue’. His comments quoted in this article are the rambling. Firstly, Britain cannot ‘devalue’ because it has a floating currency. Currencies have moved every month by up to 10% in each direction for years – this flexibility is an economic advantage. Secondly, most countries in the world are deliberately trying to depreciate their currencies to make their exports cheaper / more competitive. So if the currency went down it would be a good thing – it would boost jobs and pay. Thirdly, we are not in the ‘eurozone’, so we are already outside Europe’s economy. We control our own monetary policy (interest rates, money supply, etc.) already! So leaving will make no difference to this. This is why ‘leaving’ will have no real impact on the currency or economy in the short-run – either up or down. We are not part of the euro zone or any exchange rate mechanism. If we vote leave tomorrow, on Friday the economic effect will be….nil. There will however be long-run economic benefits if we can negotiate new trade deals, reduce regulations, increase direct democracy and introduce a points system for new comers. All four of these are proven to boost an economy in the long-run. The real reason why Soros, Kissinger, Obama want us to stay in is they want us to be controlled…..by them. If we leave we become free! We also become economically better off because we are free.

Well you THAT one wrong didn’t you. 1 British Pound equals 1.31 US Dollar 08/08/2016 1 British Pound equals

1.18 Euro

Not much movement there then!!

Exports cheaper except that Manufactured goods only account for 12% of GDP and much of that is Foreign owned and will undoubtedly relocate to EU sites.

Imports Much more expensive. Thus what few manufactured goods made from imported materials go UP in price thus negating effects of lower pound.

Finally “Freedom is just another word for NOTHING LEFT TO LOSE”

having only scratched the surface it seems that the main providers/supporters/funders of LSE seem to be big US multinational corps etc, what possible reason could they have in getting involved in the Little UK’s Referendum on the EU? couldn’t be anything to do with TTIP!

Claim that houeholds will lose a minimum of 850 GBP ?? That will , presumably, be an average. So how much would someone on say 26,000 GBP lose ( ie. someone getting tax credits) and how much would someone on 35,000 GBP lose. On the other hand, house prices and rents should not rise as much. Wages would not be driven down by immigration. Figures are often cooked up to frighten the poorer people – so can we have some more accurate estimates for these people.

And , on the other hand, how much are our annual payments likely to rise ? How much might we have to contribute to such things as baleouts ? How much would the cost of housing, supporting etc. x numbers of extra migrants a year ? How much extra cost to housing, education, social services and the NHS ? And anything else we might have to pay for if we stay in ? How are all these costed to the individual purse ?

Germany’s net exports to the UK (UK exports – UK imports) were > €50bn in 2015.

You have no credibility when claiming ‘About half of the UK’s exports go to the EU, whereas only 10 per cent of the EU’s exports are destined for the UK, so the bargaining power is lopsided.’

Just as with the refugee crisis where Germany set EU wide policy, it will be Germany that will set the terms of EU trade with the UK. And those MEPs and unelected heads who want some sort of punishment will be ignored. And France, who used to co-drive the EU project, is increasingly irrelevant given their increasing economic fragility.

(https://www.destatis.de/EN/FactsFigures/NationalEconomyEnvironment/ForeignTrade/TradingPartners/Tables/OrderRankGermanyTradingPartners.pdf?__blob=publicationFile)

In the long run Norway, Switzerland, Singapore have all become richer than most EU nations. You cannot really know the long run but if it is like the long run for developed, non-EU nations it looks rosy.

The simplest way to see the effect of the EU on the UK economy is to compare OECD countries for economic growth. If you do this you will find almost no effect.

A very interesting contribution to the debate on the economic losses and gains of Brexit.

My question is how far should analysts factor in the EU’s very strict Competition rules that ensure fair competition and the removal of anti-competitive practices? Countries outside this EU frameworks are subject to no regulation except WTO rule, is that not the case. Would that not affect the UK? After all the WTO trade disputes take a whole year to process (according to WTO itself) and more if there is an appeal. Doesn’t that make world trade rather more of a jungle for the UK after Brexit?

After all, the WTO has not resolved the argument about labour standards and does not impose any, merely stating there is a consensus that forced labour, child labour and discrimination should be avoided, but “The WTO agreements do not deal with labour standards as such”.

Is Brexit, i.e. a sovereign UK representative to the will of its people and not run by faceless corrupt and ‘United States of Europe’ inclined Eurocrats, worth any economic costs? Resoundingly yes. There is no price too high for self-determination from this dangerous ‘union’.

LOL! Academics and economists making their predictions. Like in 2008 when they failed to forecast the systemic inevitability that was financial crisis. Like in 2000 when they predicted that Britain would be bankrupted if it didn’t join the obviously flawed Euro currency, though ever since then Britain has done better than many and the Euro has entered a state of perpetual crisis. Or like David Blanchflowers now discredited predictions of mass unemployment and severe recession when the UK government took to a policy of austerity.

Every word of this article screams bias. Basic factors such as the social and structural costs of mass immigration (the top British concerns) are ignored. Export opportunities from currency devaluation are ignored. The fact that Britain is the EUs biggest single trade customer in the world is conveniently left out, and the % of trade figure is used out of context to imply that the EU doesn’t need UK business.

I’m sure the authors of this article got a lot of approving nods from their cosmopolitan peer group. I doubt the wider electorate will be so “nuanced”.

Do you factor in the cost of staying e.g. the effects of migration on wages and housing costs, and the extra cost of subsidising new members like Turkey etc.? Will you be doing research on the risk of remaining in the EU please/