Did reforms introduced in the late 1970s lead to the demise of the Westminster administrative tradition, as it is often argued? Christopher A. Cooper focuses on an important tenet of this tradition: the permanency of civil servants. He argues that reforms better reflect a pattern of institutional layering on top of the Westminster tradition, rather than constituting its demise.

Did reforms introduced in the late 1970s lead to the demise of the Westminster administrative tradition, as it is often argued? Christopher A. Cooper focuses on an important tenet of this tradition: the permanency of civil servants. He argues that reforms better reflect a pattern of institutional layering on top of the Westminster tradition, rather than constituting its demise.

May 3, 1979, is seen by many as a solemn day in Britain’s administrative history. Believing that senior bureaucrats were more concerned with maximizing their department’s budget than with accomplishing the government’s policy agenda, newly empowered Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher introduced a series of reforms to control the bureaucracy and ensure that administration was subordinate to politics. Many political pundits and scholars have interpreted these actions as constituting the death of the Westminster administrative tradition in Britain.

But how accurate is this common understanding of Britain’s administrative history? Did the reforms introduced by control-obsessed governments really bring about the Westminster administrative tradition’s demise? Have the tradition’s tenets of merit recruitment, permanent positions, and anonymity disappeared from Whitehall?

One cannot be blamed for being somewhat sceptical. Bureaucracies are notoriously rigid. They are large, hierarchical, and rule bound, all of which makes them resistant to change. Tony Blair’s memoir is rife with frustration of bureaucrats who embody the classic Westminster administrative tradition. Although he became Prime Minister almost 20 years after Thatcher first introduced her reforms, Blair claimed that “The Sir Humphrey character in the TV series, Yes, Prime Minister was a parody and a fiction, but he was the closest parody could come to fact”. Sir Humphrey Appleby, after all, was persistent in his efforts to resist and thwart any attempt to reduce his bureaucracy’s power: “if the right people don’t have power, do you know what happens? The wrong people get it: politicians, councillors, ordinary voters!”

Measuring the tradition’s vitality: permanent secretaries

The vitality of the Westminster tradition over the last several decades can be better judged by measuring its particular tenets over time. One essential component believed to have been targeted by reform-minded governments is the permanency of senior bureaucrats.

While the tenet of permanency holds that the careers of civil servants are isolated from political influence, and unaffected by transitions in government, many scholars suggest that since the 1980s there has been an increased politicization of bureaucratic appointments, especially when a new government is elected. This politicization is because each government wants individuals to be committed to its policy agenda, and is not the same thing as partisan patronage, typically associated with a spoils system, where governments use public offices to reward party supporters. In her memoir, Thatcher stated that when appointing permanent secretaries she was not interested in whether the individual was loyal to her party. Rather, what she wanted was someone who was “one of us” – committed to her policy agenda – and that:

It became clear to me that it was only by encouraging or appointing individuals, rather than trying to change attitudes en bloc, that progress would be made. And that was to be the method employed.

The vitality of the Westminster tradition can be investigated by examining the permanency of permanent secretaries over the last several decades. To do this, I measured year-over-year turnover of permanent secretaries in each ministry between 1949 and 2014. If control obsessed governments have increasingly politicized the appointment of bureaucratic appointments, we should see a larger rise in turnover among senior bureaucrats following a change in government in the contemporary period.

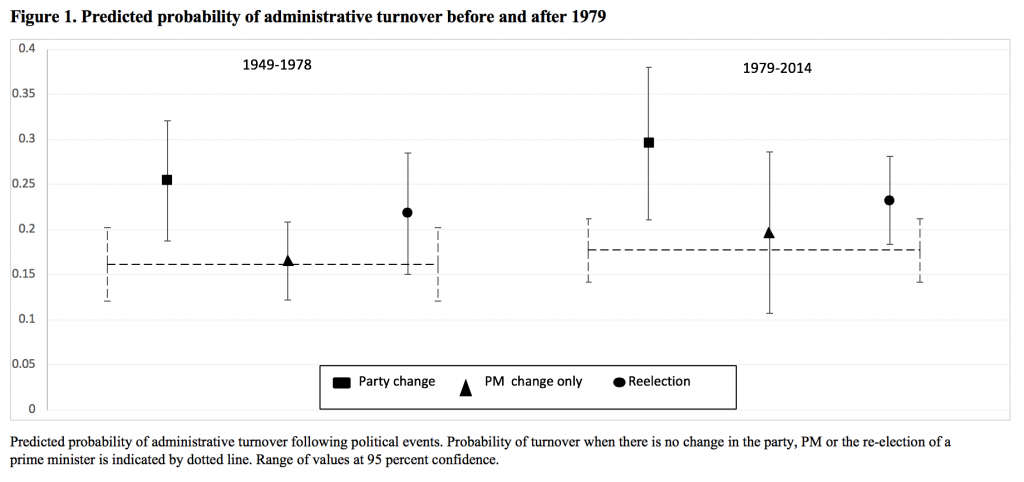

I therefore examine the relationship between bureaucratic turnover and three political events that are believed to push governments to appoint senior bureaucrats. Specifically, a change in the governing party, a change in prime minister when the party stays the same, and the re-election of government. I examined the relationship these political variables have with bureaucratic turnover in years between the 1949 and 1978 and again in years between 1979 and 2014, and also controlled for additional factors possibly affecting turnover such as the length of time the permanent secretary has been in their position and the political party in power.

Figure 1 displays the predicted probability of turnover in the two years following each political event during these two periods.

The results show that the permanency of permanent secretaries has not been increasingly politicized since 1979. A change in party, a new prime minister, and the re-election of a government lead to a rise in bureaucratic turnover in the contemporary period as much as they did in the first three decades following the end of the Second World War. Claims that power-hungry governments since the late 1970s have brought forth the demise of the Westminster administrative tradition, do not accurately describe the permanency of Britain’s most senior bureaucrats. This does not mean that bureaucratic turnover is unaffected by politics in the contemporary period, but rather, that in contrast to claims frequently made: the politics of bureaucratic turnover has not intensified.

What does this mean for Britain?

Almost 170 years ago the Northcote-Trevelyan Report hailed the merits of a civil service staffed by a body of permanent officials. While observers from many countries around the world have expressed concern over what appears to be an increasing politicization of the bureaucracy, including other Westminster countries, the findings of this study bring some much-needed good news. The title of Britain’s most senior administrative officials continues to accurately describe them: permanent secretaries.

________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in British Politics.

Christopher A. Cooper is an Assistant Professor in Public Management in the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa.

Christopher A. Cooper is an Assistant Professor in Public Management in the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Wikimedia/Fair use.