In their large-scale field experiment, Denise Baron, Florian Foos, Joshua Townsley, and Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte find that advocacy organisations can successfully mobilise their supporters to put pressure on legislators, but it’s the email itself and not necessarily the message that has the greatest effect.

Ask any political campaigner, and they’ll confirm that a campaign’s email list is one of its most valuable assets. A substantial email list can take years to build and cultivate, and most national political campaigns in the United States and United Kingdom have entire teams devoted to its operation, maintenance, and analytics. But when your organisation really needs it, can your email list deliver? We set out to study the efficacy of such mass email campaigns, especially in mobilising supporters to put pressure on elected officials. We worked with People’s Vote UK, the major non-partisan anti-Brexit advocacy group, to conduct a field experiment, which resulted in the first academically published, large-scale experimental test of email mobilisation for constituent-to-legislator lobbying.

While issue advocacy campaigns commonly use their email lists for such purposes, little research exists on the subject. For instance, a number of American advocacy groups have asked their supporters to email legislators, about voting against the confirmation of Supreme Court Judge nominee Brett Kavanaugh or supporting the impeachment of President Trump. Such attempts to mobilise supporters to pressure decision-makers are often employed by organisations and campaigns on the cosmopolitan side of the spectrum. Despite how common this is, there’s little empirical evidence on the effectiveness of such efforts to mobilise supporters to lobby their representatives.

We set out to address that gap with a large-scale field experiment conducted during a high-profile legislative battle in summer 2019. The People’s Vote (PV) campaign launched an online tool, enabling constituents to email their MP encouraging them to support an additional referendum on Brexit and prominently displayed this tool on their website. The PV campaign identified 119,362 supporters on their email list, who lived in constituencies represented by 346 MPs who were, at that time, not supportive of the campaign’s aims. These supporters were randomly assigned to one of four email treatment groups or a control condition (no email). All four email treatments asked the supporter to email their MP about supporting another Brexit referendum:

- made this ask in very simple terms (which were repeated in the following three conditions)

- mentioned that their MP supported Brexit

- mentioned the time limitations and urgency of this request

- mentioned both their MP’s support of Brexit and the time limitation

In the week after these emails were sent out, 3,622 individuals used the online tool to send an email to their MP. Of these, nearly all of them (3,402 individuals) were included in our experimental sample; 3,373 were assigned to one of the four email conditions, 29 were in the control group, and 220 individuals could not be matched to our experimental sample.

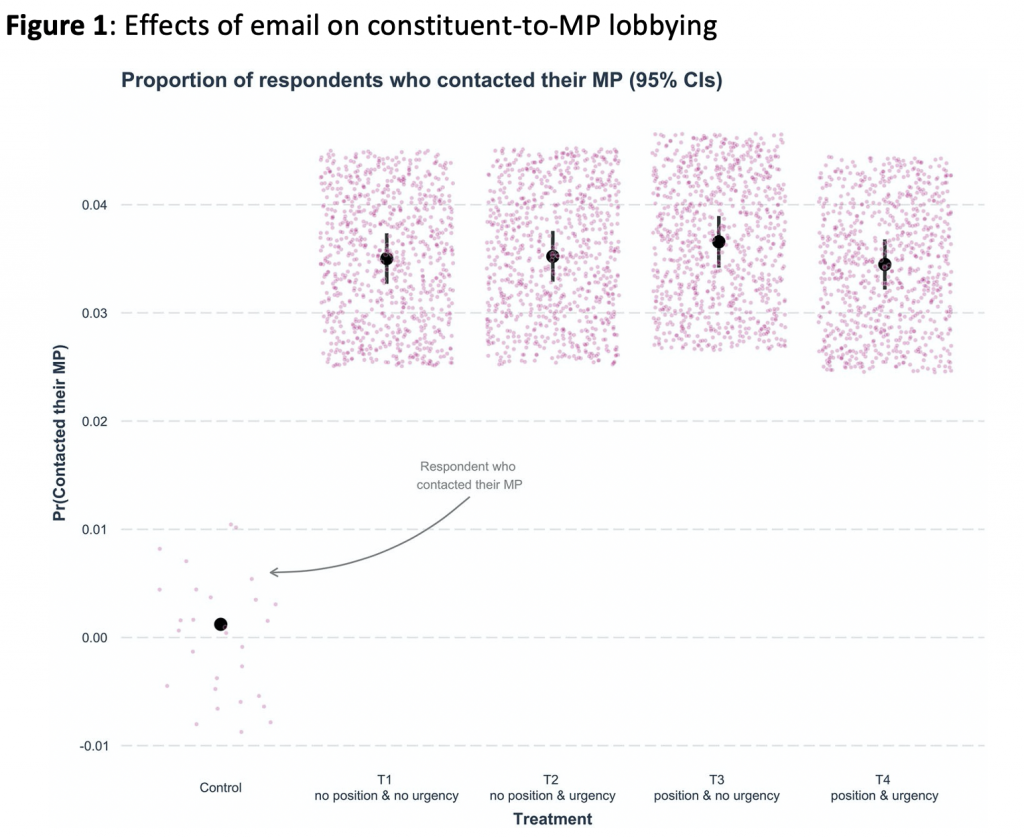

As you can see in the figure below, asking pre-identified supporters to lobby their representative was effective. We did not, however, observe any statistical differences in the efficacy of the different email conditions. The various combinations of asking a supporter to write to their MP because of their (i) pro-Brexit position or, (ii) because of the urgency of the moment, did not perform any better than simply asking the supporter to contact their MP.

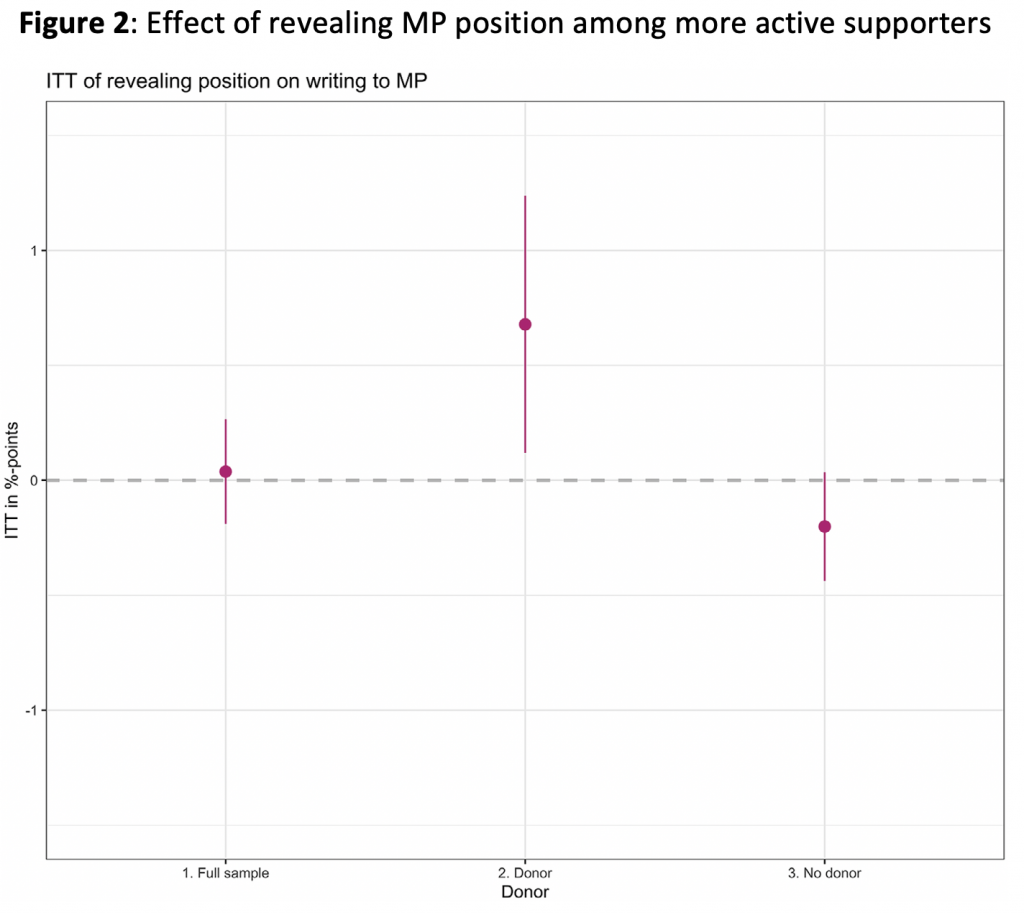

On average, the MP’s position and urgency cues were equally effective as the most basic version of the email, meaning those cues did not encourage more supporters to email their MPs. However, a look at the most engaged supporters reveals something different. Supporters who had previously donated to the PV campaign were more likely to email their MP when informed of the MP’s Brexit position, suggesting that the level of engagement with a campaign influences which messages are most effective in spurring action.

Overall, this study demonstrates that issue advocacy groups and political campaigns can employ their email lists to mobilise supporters and lobby elected officials when the political stakes are high. But why didn’t we see a difference between the different email conditions? Previous theories suggest that political participation results from a combination of resources, motivation, and opportunity (i.e., being ‘asked to’), and our study addresses the latter. In this instance, opportunity was the crucial element. Our results suggest that supporters wrote to their elected officials because they were provided with an easy opportunity and asked to do so.

Moreover, these results have considerable repercussions for issue advocacy campaigning and digital mobilisation of supporters, because they indicate that when the stakes are especially high, the traditional messaging tools of ‘naming-and-shaming’ a legislator for their position or using urgency and time sensitivity of an action are no more effective than sending a short and direct appeal. In this case, it was more important that the campaign asked their supporters to write to their MP than it was to employ one of those traditional messaging tools. Would we observe similar results in a less controversial political moment? Are high engagement supporters often influenced by different messages than their low-engagement counterparts? The more that we employ large-scale field experiments like this, the more nuanced our understanding of email mobilisation will be.

______________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ recent article published in the European Journal of Political Research.

Denise Baron is a political strategist and PhD candidate in the Methodology Department at LSE.

Denise Baron is a political strategist and PhD candidate in the Methodology Department at LSE.

Florian Foos is an Assistant Professor in Political Behaviour Department of Government at LSE.

Florian Foos is an Assistant Professor in Political Behaviour Department of Government at LSE.

Joshua Townsley is a Behavioural Scientist.

Joshua Townsley is a Behavioural Scientist.

Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte is an Assistant Professor in Political Science at the University of Southampton.

Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte is an Assistant Professor in Political Science at the University of Southampton.

Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash.