Drawing on new Resolution Foundation research, Karl Handscomb explains that each of the three policies introduced to directly protect household incomes during the pandemic has been targeted at different age groups. These patterns reflect a mixture of ingrained generational differences in the UK’s labour market pre-COVID, the nature of the initial shock to economic activity, and the design of the social security system. They also give an indication to who might be financially at risk when the schemes come to an end.

Drawing on new Resolution Foundation research, Karl Handscomb explains that each of the three policies introduced to directly protect household incomes during the pandemic has been targeted at different age groups. These patterns reflect a mixture of ingrained generational differences in the UK’s labour market pre-COVID, the nature of the initial shock to economic activity, and the design of the social security system. They also give an indication to who might be financially at risk when the schemes come to an end.

Intergenerational effects are everywhere around us, and no less so during the coronavirus crisis. One important aspect of this is understanding who has benefitted from the much-needed additional income support introduced by the government during the pandemic: the Job Retention Scheme (JRS), the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS), and a significant boost to social security benefits. But how have different age groups benefited from these schemes?

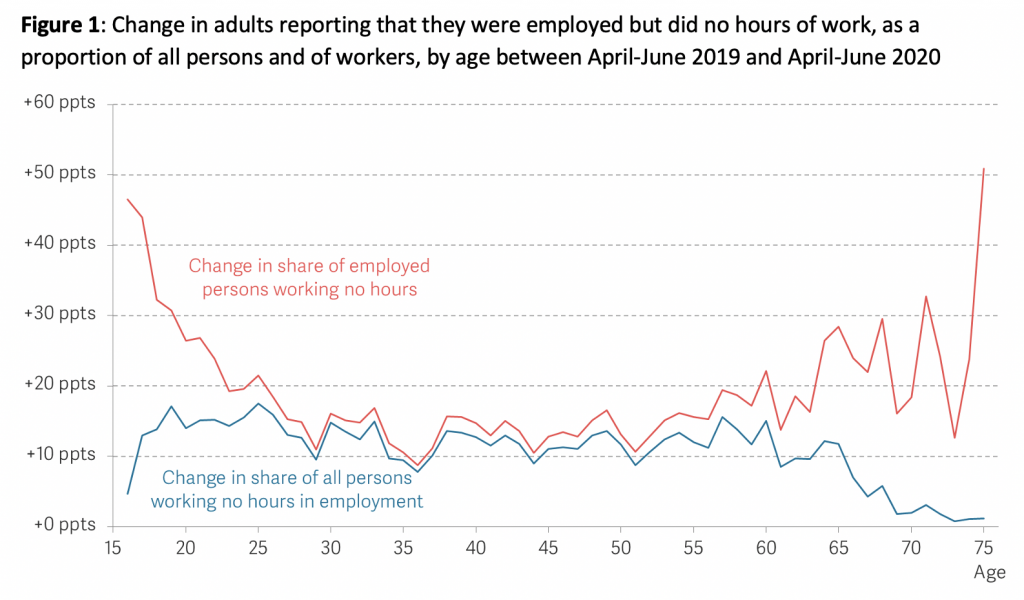

In new research we find, perhaps more by chance rather than design, that each of the three programmes have been targeted at different groups. Those in their early 20s are most likely to have been furloughed on the JRS; the beneficiaries of the boost to Universal Credit, Working Tax Credit and Local Housing Allowance are most common among those in their early 30s; and SEISS recipients are most likely to be found among those aged 50 to 55.

None of the patterns we uncover is driven by an explicit age rule in any of the three programmes. Instead, the pattern of beneficiaries reflects a mixture of ingrained generational differences in the UK’s labour market pre-COVID, the nature of the initial shock to economic activity caused by the UK’s response to the pandemic, and the historical design of the social security system.

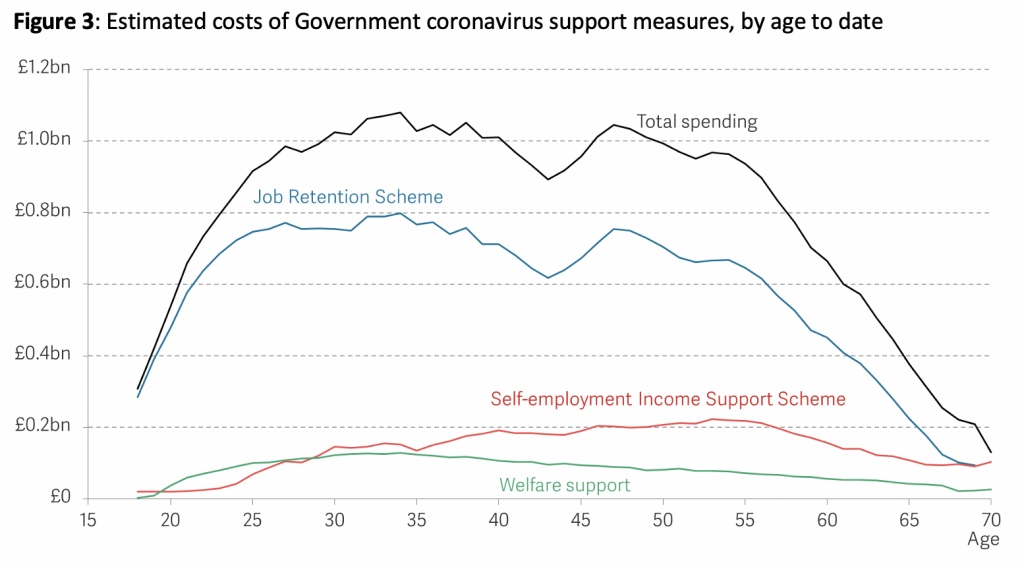

For example, the fact that the JRS has helped so many young people (20% of the nine million furloughed employees were under 25), reflects the fact that the initial shock to the labour market was heavily skewed towards the retail, hospitality and leisure sectors, all areas in which young people were disproportionately likely to work pre-COVID. In Figure 1 we can see it is young people who are more likely to have stopped working any hours during the crisis, despite fewer young people typically being in work (instead typically being in education). We should also note that, although many people have stopped working, to the credit of these support schemes they have remained attached to employment by and large, with the employment rate remaining near record highs during this crisis.

Note: taken from here and based on data from the Labour Force Survey.

Note: taken from here and based on data from the Labour Force Survey.

In contrast, the profile of SEISS support paid to 2.6 million self-employed workers reflects the older age profile of self-employment. And the age profile of the 8.7 million adult beneficiaries of the increases to social security benefits (including 1.5 million new Universal Credit claims) reflects that the UK’s social security system is considerably more generous to adults who have dependent children than those who do not, and so its beneficiaries are concentrated on the prime child-rearing ages.

Putting this all together in Figure 2, we find that the schemes are collectively more likely to provide support to people in their early 30s. But, overall, they provide a broad-based package of support that has been benefitting fairly equally those aged between 25 and 55 – reflecting the pre-COVID labour market.

Note: based on multiple sources, as described here.

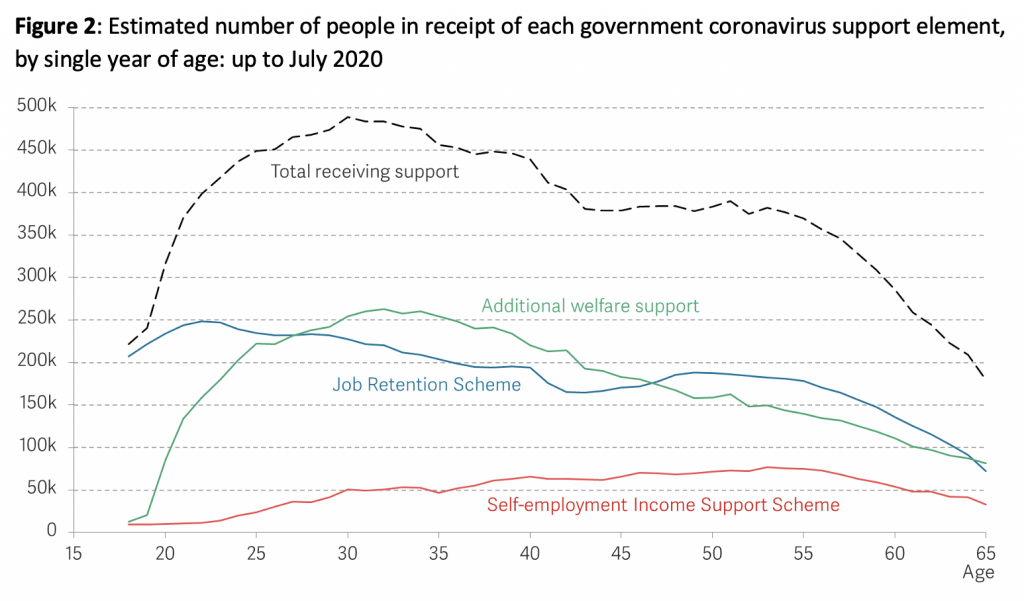

Note: based on multiple sources, as described here.

If instead of total recipients we look at total spend by age, we get a slightly different picture. Figure 3 shows that the JRS dominates the age distribution of total spending because it is by far the costliest of the three schemes. And because the JRS rules provided furlough payments based on pre-COVID earnings, there is a more even spread across the age distribution than there is for recipients, reflecting that earnings tend to rise with age. We can also see that the welfare boost makes up a much smaller share of total spending, and barely affects the total age incidence.

Note: based on multiple sources, as described here.

But what next? We are about to enter a new phase, with the JRS and SEISS due to have ended by October, and the temporary boost in benefits still scheduled to be reversed in April next year. This should give us pause for thought, because the same generational distribution of who benefited from these support packages to date is very likely to be similar to those who will be economically vulnerable in the next phase of the crisis. Young workers – especially those currently on furlough – are more likely to work in businesses that will continue to be subject to social distancing requirements. And at a time when vacancies are still half the rate of their pre-crisis level, cutting benefits is likely to lead to a 10% fall in incomes for the lowest-income households. As the crisis shows no sign of being over by March 2021, we have also called for the £20 a week increase in UC and WTC to be made permanent, to strengthen the working-age safety net and sustain – rather than stall – a living standards recovery.

_______________________

Note: the above draws on the Resolution Foundation’s report All together now? The impacts of the Government’s coronavirus income support schemes across the age distribution.

Karl Handscomb is Senior Economist at the Resolution Foundation.

Karl Handscomb is Senior Economist at the Resolution Foundation.

Photo by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash.