Until recently it was thought that what affects happiness is the mere presence or absence of a job, rather than its kind. But, as Tarani Chandola‘s new study shows, people working in poor quality jobs have higher levels of chronic stress than those who are unemployed.

Until recently it was thought that what affects happiness is the mere presence or absence of a job, rather than its kind. But, as Tarani Chandola‘s new study shows, people working in poor quality jobs have higher levels of chronic stress than those who are unemployed.

Lord Layard posed the question is “any job is better than no job” in a seminal paper in which he concluded that “human happiness is more affected by whether or not one has a job than by what kind of job it is”. This may have been true in the years leading up to the new millennium, but what about the poor quality jobs of today? Do these remain springboards to better quality jobs later on in a person’s career, just as they were in the 1990’s?

Moreover, is happiness the appropriate metric to measure employment outcomes, given that it tends to be more strongly determined by personality characteristics than occupational determinants? Work and unemployment-related stress is perhaps the more appropriate measure of employment and unemployment outcomes.

In our research paper, my co-author and I directly tested the assumption that any job is better than no job in relation to physical and mental health outcomes as well as chronic stress-related biomarkers, and found evidence suggesting that people’s levels of stress are more affected by having a poor quality job than by being unemployed.

Stressed? by aaayyymm eeelectriik, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

Stressed? by aaayyymm eeelectriik, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

We followed up a cohort of over 1000 unemployed adults who were representative of the population of unemployed adults living in the UK in 2009-10 from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. We then compared what happened to the health and stress levels of those who remained unemployed and those who got jobs of both good and poor quality. We measured a number of objectively measured biological measures that are correlated with the normal and abnormal stress responses, known as the allostatic load index. We also measured job quality in terms of low pay, low job control, high insecurity, high dissatisfaction and high job-related anxiety.

Unsurprisingly, those who found work in good quality jobs had a big improvement in their mental health. Moreover, those with any job, whether it is a good or bad job, had a bigger increase in their household incomes than those who remained unemployed.

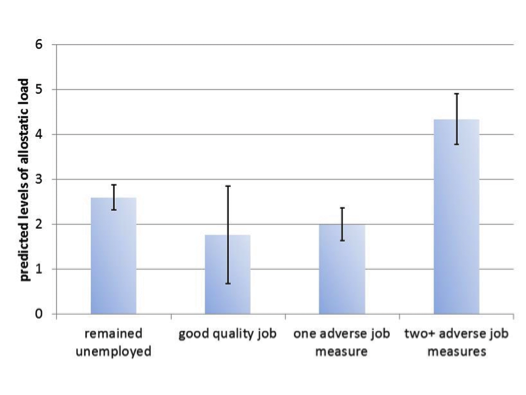

However, contrary to the “any job is better than no job” assumption, we found that the improvements in the mental health of formerly unemployed adults who became reemployed in poor quality work (with two or more adverse job measures) were not any different from their peers who remained unemployed. More significantly, as shown in the figure below, those who were working in poor quality work actually had higher levels of allostatic load (chronic stress-related biomarkers) than their peers who remained unemployed.

Figure 1. Predicted levels of allostatic load (chronic stress-related biomarker levels) by job quality/transition categories: Understanding Society waves 1-3

We also examined the possibility that the unemployed adults who subsequently were employed in poor quality jobs had worse health and more stress at the start compared to their peers who remained unemployed. But this was actually not true. As many others have found, there are strong selection pressures into employment, and healthier people are much more likely to find work (any type of work, whether good or bad) than unhealthier people.

So does this mean unemployed people should refuse job offers that are characterised by low pay, job insecurity and stressful working conditions? Unfortunately, very few will be in such a fortunate position – to be able to refuse a job. Only about 20 percent of the unemployed cohort initially were in receipt of unemployment-related benefits, which means most were living off other sources of income including income transfers from family and household members.

Instead, the importance of good quality work should be high on the government’s agenda, with the publication of Matthew Taylor’s review of modern work practices. The report outlines strategies that could enable the call to “make all work good” a reality, strategies that include ensuring a minimum wage for all workers or a “fair rate” for all work produced, and allowing flexibility around working conditions that benefit the worker, not just the employer.

_________

Note: This article was originally published at LSE Business Review.

Tarani Chandola is a Professor of Medical Sociology. He joined the University of Manchester and the Cathie Marsh Institute in April 2010, was the head of the Disciplinary Area of Social Statistics (2012-2014) and the director of the Cathie Marsh Institute (2013-2016). He was formerly at the UCL Research Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, and prior to that completed his PhD and post-doc at Nuffield College, University of Oxford. He is a co-director of two ESRC centres: the National Centre for Research Methods (NCRM) and the International Centre for Lifecourse Studies in Society and Health (ICLS). Tarani’s research is primarily on the social determinants of health, focusing on health inequalities and psychosocial factors, and the analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Much of his research is on stress at work and its effects on health and related biomarkers. He leads the academic network on Health, Work and Wellbeing, sits on the Health & Work advisory board for Public Health England and chairs the scientific advisory board for the ESRC Research Centre on Micro-Social Change Centre (MiSoC).

Tarani Chandola is a Professor of Medical Sociology. He joined the University of Manchester and the Cathie Marsh Institute in April 2010, was the head of the Disciplinary Area of Social Statistics (2012-2014) and the director of the Cathie Marsh Institute (2013-2016). He was formerly at the UCL Research Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, and prior to that completed his PhD and post-doc at Nuffield College, University of Oxford. He is a co-director of two ESRC centres: the National Centre for Research Methods (NCRM) and the International Centre for Lifecourse Studies in Society and Health (ICLS). Tarani’s research is primarily on the social determinants of health, focusing on health inequalities and psychosocial factors, and the analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Much of his research is on stress at work and its effects on health and related biomarkers. He leads the academic network on Health, Work and Wellbeing, sits on the Health & Work advisory board for Public Health England and chairs the scientific advisory board for the ESRC Research Centre on Micro-Social Change Centre (MiSoC).

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

“This may have been true in the years leading up to the new millennium, but what about the poor quality jobs of today? Do these remain springboards to better quality jobs later on in a person’s career, just as they were in the 1990’s?”

I doubt it was ever true. Many unskilled jobs in the 90s were a springboard to nothing.

I worked in unskilled repetitive factory work in the 80s. The job had a very negative impact on my mental well being. There was no springboard to anything from working there, if I had stayed 40 years I would have been doing the same thing.

When I finished work for the week on Friday there was no positive weekend feeling, I was under a dark cloud that was the thought of having to go back on Monday. With a young family, I kept up the job for no other reason than the dull compulsion of economic necessity.

Looking forward to 40 years of such an existence was depressing and resulted in several periods of sickness as a result of depression,

Having had a poor education I had left school “disqualified” with the belief that I was not academically inclined.

I came to question this belief and after studying at night classes I was able to secure a place at university. This turned my life around and enabled me to pursue a future career doing work that I actually enjoyed and giving me a sense of fulfilment.

Had I not found a route out of the work I was doing, I am sure I would have fell victim to long term sustained depression.

You state that “Only about 20 percent of the unemployed cohort initially were in receipt of unemployment-related benefits”. It would be interesting to see the unemployed group on the bar chart divided into these groups.

I wonder how much more stressful it is being unemployed without benefits than with. And if those without still have more stress than those in worst jobs?

Really interesting piece of research Tarani .

How much of this is social programming – Our sense of value is enhanced by working because that’s just how we think we’re supposed to be?

Like the earlier poster, I’m lucky, I love what I do. But I’ve done plenty of jobs that haven’t given me the same satisfaction.

Results are always the same. I don’t much like getting up early. I get sleepy/bored in the afternoons and think I should be better paid.

Yes if you eliminate welfare than any job will be better than no job at all.

We cannot have people earning more from welfare than work!

Cary Michael Cox

The article states “Only about 20 percent of the unemployed cohort initially were in receipt of unemployment-related benefits” implying that even those not receiving welfare were better off (in terms of stress) than those in the worst jobs. So your point doesn’t stand

Of course, it’s forgotten that looking for a job is, in fact, a job in itself, but it’s an unpaid job and costs the unemployed both money, time, energy, effort and stress, not to mention insomnia and bad dreams, social stigma, especially in the land of work ethic, Protestant or anything else.

I’m a special case because I have a calling; not one, but two. I’m trapped in a sense because it goes much deeper than dedication. Human beings don’t understand the walking a mile in my moccasins because it is too alien for normal society. For, you see, I’m a classical musician and an artist. I’m not a bohemian or a nonconformist. It’s survival, Jim, but not as we know it! Following your bliss is infinitely better than following money. Human beings fail miserably to understand that. Society doesn’t get it. Follow the money! That’s the answer to every mystery problem. But that’s your society, not mine. My work has always been about quality or I refuse to do it. What can they do to me? Fire me? That’s meaningless and worthless to me. I can’t be bought so easily as that. But, good luck to the workers and embrace the robots and replicants in future. Our species has both outgrown the earth and destroyed it for human habitation. Trump has 2 nations to nuke, so, depopulation might yet be the solution to liquidating the problem: us!