Will this December’s general election prove a watershed contest, or a repeat of the status quo? To help make sense of developments, Pippa Norris discusses various distinct types of election outcomes and their application to the current UK context.

Will this December’s general election prove a watershed contest, or a repeat of the status quo? To help make sense of developments, Pippa Norris discusses various distinct types of election outcomes and their application to the current UK context.

After a series of parliamentary defeats and constant frustration in attempts to get his Brexit deal passed, Prime Minister Boris Johnson decided that rolling the dice on a UK general election on 12 December, although a high-risk strategy, was the least-bad option left. Is the outcome likely to crack the durable structure of party competition at Westminster and in the electorate? In particular, will it prove a watershed contest, with the Leave-Remain division over-riding traditional party loyalties?

To make sense of developments, we can turn to several ways that political scientists typically think about distinct types of outcomes, including whether elections are maintaining, dealigning, or realigning contests.

A maintaining election?

Party politics are in a state of constant flux, following the fortunes of the latest opinion poll or parliamentary division. Commentators emphasize that today the electorate is more volatile than ever, with the outcome of the general election proving unpredictable and risky. Poll trackers show surges and sudden reversals in party fortunes – the rise of Brexit and the Lib Dems during the European Parliamentary contests, then the revival in Conservative support following Boris Johnson’s anointment. An unpredictable outcome is exciting for journalists desperately trying to flog interest in the campaign among the Brendas from Bristol who prefer to be making their mince pies than watching party political broadcasts. Many ‘Don’t Knows’ in opinion polls are a classic signal of dealignment uncertainty.

Nevertheless, in maintaining contests, despite voter flux, indecision, and churning, the party order still endures, with one party often predominant in government over a series of contests. The relatively enduring features of UK politics persist across successive elections. Party systems in long-established democracies involve patterned, stable and predictable interactions in the competition for seats and votes. Maintaining elections reflect the status quo: there are no strong issues, events or major shifts in party policy to deflect voters from their habitual electoral preferences. Each party mobilises its ‘normal base’ of support. This concept requires splitting the actual vote cast for a party into two parts: a ‘normal’ or baseline vote to be expected from a group, based on their behaviour over successive elections in the past, and the current deviation from that norm, due to the immediate circumstances of the specific election.

The Labour campaign platform is based on the assumption that the outcome will revolve largely around ‘politics as usual’ – more spending on the NHS, no tuition fees, free childcare, higher wages. It could be 2017 all over again. This is similar to the Democratic presidential contenders betting the house on healthcare, not highlighting the third-rail of immigration. And, not to be out gunned by Labour, the Conservatives have responded with their own series of generous spending pledges, splashing the cash on ‘new’ hospitals and the like.

If this contest maintains the status quo, the potential outcome could be the return of another hung parliament, failing to break the impasse at Westminster. The Remainers would still be divided. The Conservatives would remain the largest party but without an overall parliamentary majority, and, under Johnson’s Brexit deal, with doubts about prospects for a revived parliamentary alliance with the DUP.

Deviating contests: Flux, not flow

By contrast, in deviating contests with a de-aligned electorate, weak partisan anchors are evident. Sharp swings in support towards one party are possible – but in deviating contests these do not endure, so that equally strong counter-surges in subsequent contests remain equally likely. In deviating elections, particular personalities, issues, or events produce a temporary sharp reversal in the ‘normal’ share of the vote for major parties. Deviating contests are characterised by negative protests against the government, which cause dissatisfied voters to defect temporarily to minor parties, only to return home in subsequent contests.

Partisan dealignment is nothing new; it has been observed since the 1970s. But events and deepening divisions over Brexit at Westminster, with dramatic internal splits weakening party discipline in the Commons, are likely to have further dissolved the glue of Conservative and Labour loyalties in the electorate. The British Election Study, for example, found that from 2010-2017, across three elections, almost half the electorate did not vote for the same party. Personalities, events, and specific issues may encourage base defections from all parties on polling day – notably Corbyn’s deep unpopularity and internal fissures dividing Labour moderates and hard-liners, Johnson’s ‘death in a ditch’ failure to deliver anything on 31 October, the Lib Dem bold but risky Remain stance, revived stirrings of independence in Scotland, and Farage’s guerrilla war for a No Deal Brexit.

Frustration and anger over Brexit makes protest voting more likely – but the impact of negative partisanship is highly unpredictable in multiparty systems. Flux makes it easier for some modest seat gains by the SNP, Lib Dems, Greens, and Independents. But it is also possible that Brexit has sucked all the oxygen out of the room. The majoritarian First-Past-the-Post system props up the two-party system and penalizes geographically-dispersed parties. Once Brexit is ‘done’ with a formal withdrawal agreement – in the sense that the UK severs its ties with the EU though facing years of trade negotiations – under this scenario, despite some temporary losses, ‘normal‘ two-party party battles will resume over the standard domestic agenda of health and education, jobs and poverty, spending and taxes, climate change and crime. In this sense, the outcome could be change plus ça change.

…Or realignment along Leave-Remain cleavages

Alternatively, however, the UK could be experiencing that once-in-a-lifetime phenomena, more often predicted than observed: a critical realignment. The concept of critical realignment has a long pedigree, particularly in American political science, which has conventionally divided the party order into distinct historical eras. The theory of critical election originated with V.O. Key (1955) and the extensive literature generated by this work has long debated the historical periodization of party systems. Dispute continues about the magnitude, durability and direction of electoral change, and its enduring consequences for party government, in order for contests to qualify as a case of critical elections. President Trump’s victory in the 2016 U.S. election, reflecting a hostile take-over of the Republican party by authoritarian-populist forces, is the most obvious contemporary case – although it is unclear whether the key signs of change started with the Tea Party movement under Obama, and heated debate remains about the persistence and legacy of Trumpism beyond Trump.

Classifying recent elections as a critical realignment, without the benefit of hindsight, is often highly problematic. It is far harder to distinguish distinct party systems in the UK; the years from the expansion of the franchise during the mid-Victorian era to the first World War were a period of Conservative-Liberal predominance based on rural and religious cleavages in the electorate. The 1918-39 period, following the rise of Labour and the politics of class, was characterized by a complex and unstable three-party system. By contrast, the era from 1945 to 2010 can conventionally be seen as exemplifying the predominance of two-party class politics at Westminster – but cracks started to appear beneath the surface as early as the 1970s.

In the past there have been many false dawns of breakthroughs predicted by over-excited headline writers as new parties like the SDP or the Greens or UKIP/the Brexit Party have temporarily surged at the polls in second order contests, exemplified by byelections and European elections, only to fall back in subsequent contests. In the aftermath of the Tory landslide of 1983, and Foot’s nadir, many claimed Thatcherism was invincible. Similar hopes surrounded the false new dawn of Blair’s 1997 sweep. As with any predictions, we can only provide cautious interpretations of the current political landscape which may, or may not, be borne out by subsequent events. Psephology is far more like a provisional medical diagnosis based on exploratory surgery than the laws of physics. We will only know the full extent of the change in electoral behaviour which occurred in 2019 after subsequent contests either consolidate or reverse the alterations. Nevertheless, we can speculate whether this election shares some of the characteristics of critical elections in the past, in Britain and elsewhere.

There are basically two types of realignments.

Secular realignments: OK, boomers

These are elections characterised by an evolutionary and cumulative strengthening in party support over a series of elections. For V.O. Key, the American party system maintained a stable equilibrium for long periods of time, over successive elections the pattern of voting by different regions, counties, and social groups was largely predictable. But the party system could evolve due to a gradual shift in the electorate over successive elections, with the more or less continuous creation of new party-voter alignments and the decay of the old. This familiar model gives primacy to broad socio-demographic developments, such as demographic turnover in the electorate and socio-economic trends which gradually produce long-term shifts in the composition and values of the electorate.

Much attention in voting studies has focused on understanding long-term secular trends in post-industrial societies, including the growth of new social cleavages and the process of generational value change which may glacially transform the electorate. The most plausible candidate for secular realignment in the UK concerns the steady fading of class divisions as predictors of party choice in the electorate – and its replacement by a widening and substantial generational gap. Secular realignment model produces an incremental, durable and persistent strengthening in the long-term contours of party support. Elsewhere in Cultural Backlash I have argued that the rise of authoritarian-populism can be attributed to a tipping point in the balance of forces dividing social conservativism and social liberalism, fuelled by enduring generational value shifts. Generation (and education) replaces social class as the core cleavage in the electorate.

Critical realignments

Lastly, critical elections are exceptional contests which produce abrupt, significant and durable realignments in the electorate. with major consequences for the long-term party order. Critical elections have significant consequences, not just for a single administration, but also for the dominant policy agenda of successive governments. In this sense the pendulum of party competition ratchets decisively in a new direction. While every contest sees some electoral flux back and forth among parties, lasting transformations of the party order rarely occur. Critical elections are characterised by three interrelated features:

- realignment in the ideological basis of party competition;

- realignment in the social basis of party support;

- realignment in the partisan loyalties of voters.

Ideological realignment involves major changes in the programmatic basis of party competition, for example if the deep Leave-Remain cleavage over Brexit reflects a new cross-cutting issue reflecting divisions between nationalism and cosmopolitanism which continue to divide parties and the electorate long after Brexit is decided in law.

Cultural Backlash argues that the classic economic Left-Right cleavage in party competition found in many established democracies during earlier decades has faded in importance, replaced by contemporary competition over Authoritarian and Progressive cultural values, on one dimension, and the use of Pluralist or Populist rhetoric, on the other. The simple Left-Right economic cleavage over state v. markets has been replaced by a strategic game of multilevel competition. The winner-take-all nature of the Westminster electoral system means that whichever side of Brexit loses, loses big. But the electoral system at Westminster also serves as a major constraint preventing party system change, even if no longer fit for purpose in the electorate (or in hung parliaments).

Shifts can also arise if parties shift rapidly or ‘leapfrog’ over each other across the ideological spectrum, for example if Remainers abandon Corbyn to consolidate behind any parties in the Remain Alliance. Realignment can also be signalled if the Brexit party gains seats, especially if Conservatives were ever to form a coalition with them. Social realignment concerns major shifts in the traditional coalitional basis of party support based on structural cleavages, such as the revival of the rural-urban cleavage in American politics and the fading of class cleavages in the UK.

The generational divide over the climate crisis and progressive social values is evident – but to secure a shift in power at Westminster this does require that young people turnout to vote. If Boris Johnson’s strategic appeals break Labour party ties among Leavers, forging a persistent base of Conservative support in key marginals in the Midlands and North – such as Barrow and Furness, Newcastle-under-Lyme and Dudley North – then this would count towards social realignment. Labour and the LibDems also hope to make gains in Remain seats, such as in the Greater London suburbs. Lastly, if these shifts consolidate in subsequent contests, realignments should eventually be observed in the partisan loyalties of voters.

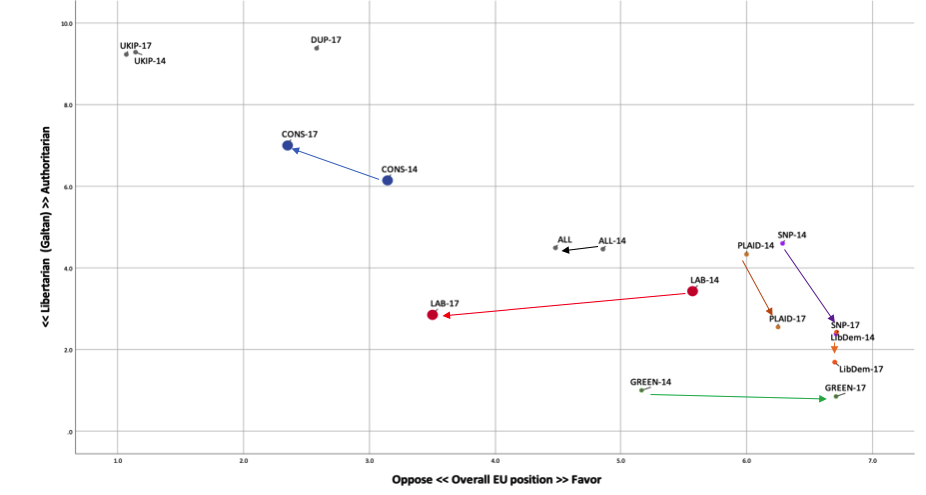

Figure 1: UK Parties respond to the 2016 EU referendum

Note: Overall EU position: the overall orientation of the party leadership towards European integration. Galtan: position of the party in terms of their views on democratic freedoms and rights. ‘Libertarian’ parties favour expanded personal freedoms, for examples, access to abortion, active euthanasia, same-sex marriage, or greater democratic participation. ‘Traditional’ or ‘authoritarian’ parties often reject these ideas; they value order, tradition, and stability and believe that the government should be a firm moral authority on social and cultural issues. Source: calculated from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey on party positions, UK only in 2014 and 2017.

Note: Overall EU position: the overall orientation of the party leadership towards European integration. Galtan: position of the party in terms of their views on democratic freedoms and rights. ‘Libertarian’ parties favour expanded personal freedoms, for examples, access to abortion, active euthanasia, same-sex marriage, or greater democratic participation. ‘Traditional’ or ‘authoritarian’ parties often reject these ideas; they value order, tradition, and stability and believe that the government should be a firm moral authority on social and cultural issues. Source: calculated from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey on party positions, UK only in 2014 and 2017.

Figure 1 illustrates how political party competition on Libertarian-Authoritarian values and on Europe, and how this changed before and after the 2016 Brexit referendum. Thus, in response to the Farage threat, the Conservative Party shifted in the top-right quadrant, becoming more authoritarian on policies of personal freedom and more Eurosceptic. Most of the opposition parties clustered in the bottom-left quadrant moved simultaneously in the opposite direction, becoming more Remain, heightening polarization over the EU. This laid the conditions facilitating the Remain Alliance. The one clear exception is Labour, which moved after the referendum towards the centerground on Europe, just at a time when the general electorate polarized. Under Corbyn’s assiduous fence-sitting, Labour adopted a position which is neither Remain fish nor Leave fowl.

Significant change across not one but all three levels in the 2019 contest would provide convincing evidence for a durable and deep-rooted alteration in the party order which is likely to persist for more than one term of office. These changes would transform the familiar geographical map of party support, threatening party heartlands, exemplified by the GOP take-over of southern states during the late 1960s. A contest which led electoral reform or Scottish independence, such as a minority Labour-government dependent upon parliamentary votes from the LibDems and SNP, would consolidate persistent changes at Westminster.

Realignment is a high hurdle, however, given churn and uncertainty among the mass electorate – and churn and uncertainty among Westminster parties as well, with moderates deserting the battleground and only true-believers left. V.O. Key identified critical elections as those ‘…in which more or less profound readjustments occur in the relations of power within the community, and in which new and durable electoral groupings are formed.’ These exceptional contests represent sudden and large breaks in the established social and ideological basis of party competition, with enduring consequences for government and for the public policy agenda. Critical elections move the party system from equilibrium to a new level and then this level stabilises and consolidates.

Whether the 2016 Brexit referenda laid the foundations for a critical realignment in the bones of the British electorate, or a more temporary period of uncertainty and flux, or simply a repeat of the status quo in a hung parliament, will become clearer once the smoke rises after 12 December. Calling the election was always a high-risk roll of the dice by Johnson. It is not hyperbole to claim that the future of Westminster party politics, the future of Brexit, indeed the future of the United Kingdom nation-state, all hang in the balance.

_____________

Pippa Norris (@PippaN15) is the Maguire Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Harvard University and the author of numerous books on British and comparative politics, including, with Ronald Inglehart, Cultural Backlash (CUP 2019).

Pippa Norris (@PippaN15) is the Maguire Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Harvard University and the author of numerous books on British and comparative politics, including, with Ronald Inglehart, Cultural Backlash (CUP 2019).

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

2 Comments