Inflation may be down, but its underlying causes haven’t gone away. Charles Goodhart argues that an ageing population with more care needs, coupled with the challenge of climate change and an increasingly hostile geopolitical situation, means that inflationary pressures and rising interest rates could become endemic.

The last thirty years were not normal. Inflation dropped to 2 per cent, sometimes lower; interest rates fell and stayed at unprecedently low levels; growth was good overall, if uneven; much of the volatility in inflation and output was due to sharp, often politically induced, fluctuations in oil prices; and finally, more people were taken out of poverty than ever before in history. There are a number of reasons for this, essentially favourable, outcome, including, crucially, demographic shifts. But it looks like the good times are now coming to an end, and that the positive outcomes of the past are likely to enter a reverse course.

Why the good times are over

The main reason for the economic success of the three decades from 1990 until about 2020, was demographic. Although birthrates had been going down in the inter-war period, there was a baby boom in most countries after World War II, from 1945 until about 1965. When the birthrate began to fall in the mid-1960s, assisted by the growing availability of effective contraceptives, it meant more women entered the workforce. In the 1940s only about 20 per cent of married women participated in the labour force. Today it’s 75 per cent. Such a large increase in women’s participation played a big role in the growth of the paid labour force and GDP.

The next main feature of this period was that China and Eastern Europe entered the world’s trading system. With China accounting for nearly one-quarter of the world’s population, this represented a huge surge in the world’s available workforce. There was a huge shift of capital and production from the West to countries where labour was abundant and cheap.

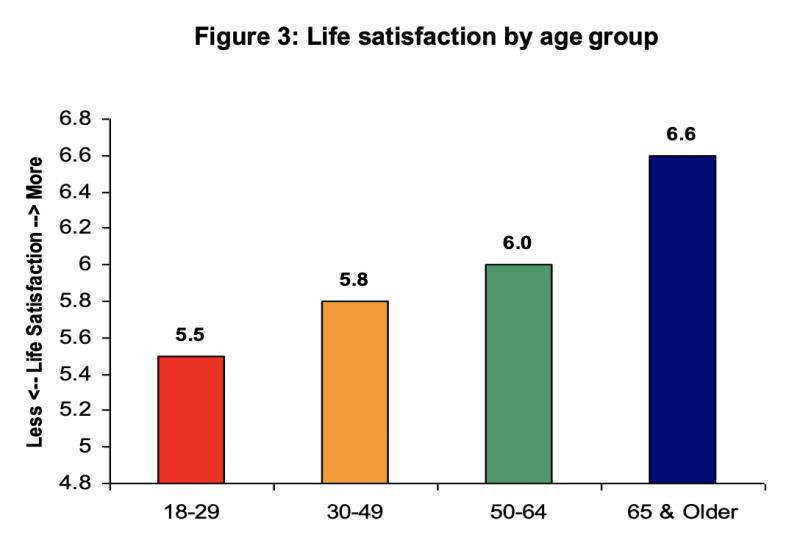

But the causes of these shifts, coupled with disinflation everywhere, are now going in reverse. The falling birthrate, together with the upwards trend in life expectancy, is leading to a sharply worsening ratio of workers to dependents, especially of the incapacitated old who need expensive care and medical support.

Until recently, life expectancy has been rising, mainly because fewer people have been dying before they reach 80 years old. Infant mortality, which had been so high in the 19th century, was largely eradicated by 1931, and has remained at very low levels since World War II. While this has been a triumph for medicine and civilisation, there’s been less progress in dealing with the illnesses of the old, such as dementia. The increase in the old as a share of population is now becoming so great that the proportion of the population suffering from such diseases is likely to rise sharply. Coupled with this trend is a continuing downwards spiral in the birth rate. In most countries outside of Africa and the Middle East, this has fallen to, or below, the level of population replacement. The combination of an increase in the proportion of the old with a fall in the size of the workforce means that the ratio of workers to those in need of expensive medical care is worsening sharply.

The policy challenges ahead

On present projections, government deficits and public sector debt remain on unsustainable trajectories, see for example the relevant recent papers on this subject by the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the UK Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). There is a pressing need, which may soon become urgent, to correct the worsening fiscal outlook. However, cutting public expenditures will be very difficult, indeed the likelihood is that public expenditures will have to rise in the near future to address issues such as climate change and the need to enhance defence, in the aftermath of the war in Ukraine. There are limits in any caring and civilised society about the extent to which cuts to care and medical support can be made.

What happened in the UK when Liz Truss was temporarily Prime Minister can now been seen as a warning of what may well happen more widely and more seriously elsewhere.

To put fiscal policies back on a sustainable track, an increase in taxation will be necessary, something that’s politically extremely challenging. The tendency among the political class is to hope for a growth miracle, pushing any fiscal problems to the future. A combination of a political reluctance to deal with our fiscal problems, combined with demographic, climate change and defence expenditure pressures, may well lead to endemic inflation, rising interest rates, and a potential bond market crisis. What happened in the UK when Liz Truss was temporarily Prime Minister and proposed an expansionary fiscal program with little concern for its sustainability, can now been seen as a warning of what may well happen more widely and more seriously elsewhere: a veritable canary in a coal mine.

The short and long-term outlook

The economic situation for the immediate future appears to look rather brighter but may well take a more troublesome turn thereafter. There are, of course, several serious problems at present. The conflict in Ukraine continues. Following the Hamas terror attack on October 7, the Middle East is aflame. The American Presidential election looms ahead, where the choice between Trump and Biden is not exactly appealing.

We will need a combination of good luck and good policies to get through the next five years unscathed.

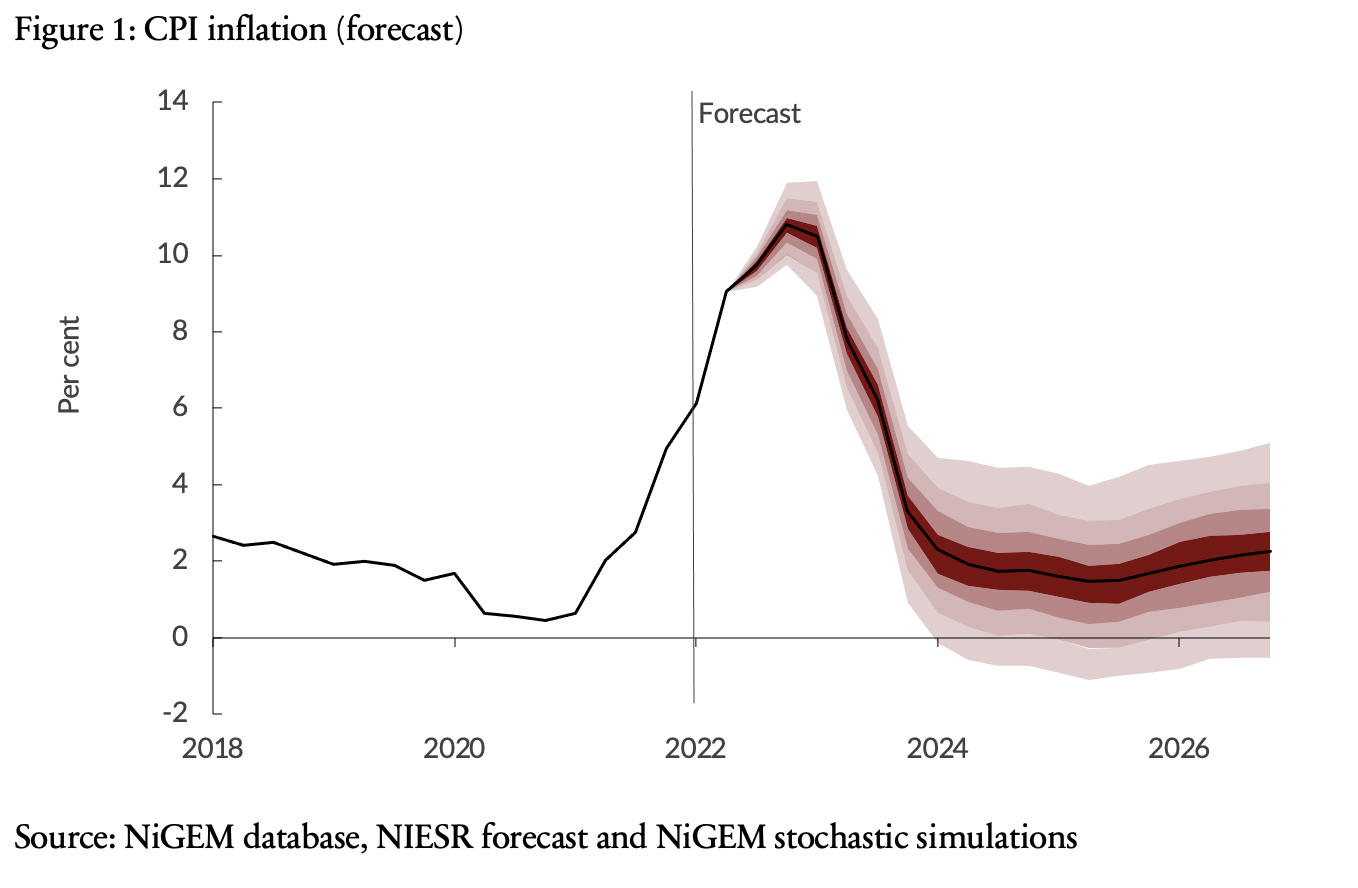

If these problems don’t get worse, the likelihood is that headline inflation (which includes food and fuel prices) will fall over the next few months to target. Given economic growth is stagnant, this will almost certainly lead to cuts in interest rates. In that case, 2024 is likely to be a comfortable year for central banks, including the Bank of England. But the underlying demographic trends and the accompanying fiscal problems remain unresolved. The longer-term outlook is problematic. We will need a combination of good luck and good policies to get through the next five years unscathed.

Public expenditure will need to rise to meet the need of care-costs for our incapacitated old, deal with climate change and to face up to potential geopolitical dangers. If we are not to avoid a financial crisis, taxation will have to increase. The question is how to do so without further worsening productivity and competitiveness. I would make two suggestions. First, that we shift much of the burden of taxation onto property and land, rather than on labour and invested capital. Second, that we take advantage of any significant reduction in the cost of fossil fuels to keep the price of consuming these high, in order simultaneously to reduce carbon emission and to provide fiscal revenue. Neither would be politically easy. But the path to yet another financial crisis is paved with concern for short-term political gains.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: TippaPatt on Shutterstock