Jennifer Brown, Terri Cole, and Yvonne Shell look at reports of increased domestic violence arising from the coronavirus lockdowns and provide some possible explanations and options.

Jennifer Brown, Terri Cole, and Yvonne Shell look at reports of increased domestic violence arising from the coronavirus lockdowns and provide some possible explanations and options.

Policies to impede the infection rates of coronavirus include lockdown. This assumes homes are safe places. They are not for those in abusive relationships. Like the virus, domestic abuse is a worldwide phenomenon. But unlike the virus, the gender balance of those adversely affected is reversed. Although rates in different countries vary, the available statistics from the UK show that in line with international comparisons, more men are infected by COVID-19; of those dying from the virus, the ratio of men to women is about 70:30. The reverse is the case for women suffering from domestic abuse or being murdered by their abuser. WHO estimates that globally, one in three (35%) of women suffer some form of abuse mostly from partners or ex-partners in their lifetime. For the year ending March 2019, the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) reported that an estimated 2.4 million adults aged 16 to 74 years experienced domestic abuse in the last year (approximately 70% of whom were women). Between April 2016 and March 2018, 20% of homicides (366) were domestic, of which 73% were women victims – that is just over two women per week are being killed.

The CSEW tells us that those subject to domestic abuse are most likely to be young, female, and between 20-24 years of age, living in an urban area – exactly the most likely scenario for confined living spaces. Features of domestic abuse include micro-managing by the abuser, often because they are not in control of other areas of their life. It is noteworthy that the presence of children is not a protective factor as CSEW statistics show – 40% of incidents occurred with children present in the household.

Research links situational factors to increased rates of domestic abuse. Brimicombe and Cafe draw on Routine Activity Theory to suggest that crime occurs as a result of the normal rhythms of everyday life and point to the stress opportunities where domestic violence occurs more frequently such as televised sporting fixtures, weekends, and hot days. Explanations included increased levels of testosterone, adrenaline flow, identification with the emotions of nationalistic or partisan fervour, arguments over TV programme preferences and all fuelled by increased consumption of alcohol. These conditions under normal circumstances served to exacerbate existing relationship tensions.

The coronavirus outbreak involves major restrictions in our patterns of life, possibly loss of income, as well as enforced physical confinement. Government guidance, and now instructions, to ‘stay at home’ is likely to increase relationship stress and pressure. Social isolation of a victim of domestic violence is a pre-existing key strategy for many abusers, something which many subject to such abuse already experience. The dynamic of social isolation in the domestic violence relationship is centred on the lack of social relationships, constrained by the perpetrator. Social exclusion is a multidimensional process in domestic violence and includes prevention of working by the partner (exclusion from the labour market), psychological consequences of the experience of violence making social relationships difficult to establish and maintain, (e.g. the experience of shame by victims leading to avoidance) economic exclusion (financial abuse), and finally social exclusion including not only control over whom the victim sees but whom they telephone, email, text etc. The latter is often insidious in nature, arriving by stealth into the relationship.

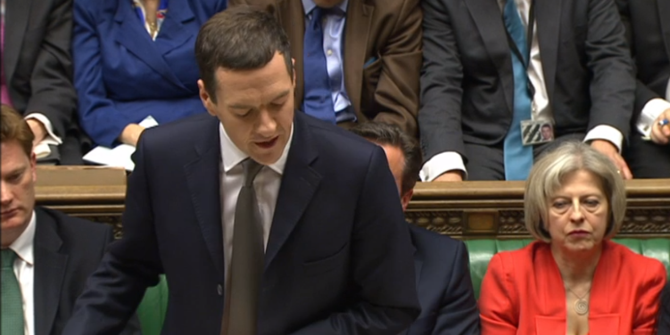

Government mandated social isolation further weakens social support and participation, thereby creating further limits on ability to consider and potentially leave the abusive relationship. It was good to the see the Home Secretary acknowledging this in her recent Coronavirus briefing.

As economic pressures begin to bite as many suffer job losses, furloughing of staff, and associated reduction in income, this inevitably will lead to escalation in stress within households but more so for those experiencing domestic violence. It is not the economic distress per se that is the issue, but rather the violation of traditional male breadwinner norms, which may well be heightened by the impotence experienced in the face of coronavirus contagion.

With mental health and wellbeing already compromised, the abused survival mode is reduced to fight, flight, or freeze. Flight is effectively removed by lockdown. Fight isn’t really viable which just leaves ‘freeze’. Enforced confinement means the abused is further subject to the rhetoric of the abuser who will be ratcheting up tactics to undermine and exercise their micro-controlling as an outlet to their increased frustration and dangerously underpinned by their pre-existing dysfunctional and damaging attachment style.

In addition, without the potential for external oversight, the perpetrator may feel more willing to engage in even greater deviant behaviour. The brakes may well be taken off and lockdown will feel like giving increased permission to wield negative power that will go unchecked and unnoticed. Having outside relationships introduces some measure of social scrutiny and deterring the abuser due to fear of the abuse being recognized by others.

We do not yet have a complete picture from the figures, but despite such difficulties and the fact that we know many incidents are never reported, Refuge – a UK national abuse helpline – has already reported a 25% increase in calls. Louisa Rolfe, the National Police Chiefs’ Council lead for domestic abuse observes that there has been a rise in domestic abuse linked to stay at home advice, and commented that in China incidents increased by a third. French Secretary of State for Gender Equality, Marlène Schiappa revealed a dramatic increase in domestic violence cases since the lockdown there started on 17 March. While domestic violence across France increased by ‘32% in one week’, in Paris it rose by as much as 36%.

What can be done when restrictions on social support, a recognized protective factor associated with domestic violence, are drastically reduced? Deputy Chief Constable Rolfe advises calling 999 if there is immediate risk of danger. If you cannot speak, press 55 after dialling 999. Check your local police website for online reporting or contact options. Try helplines such as Refuge (0808 2000247). If someone you know is subject to domestic violence, then understand that their partner will, in all likelihood, be making it even more difficult for them to get in touch with you. Maintain contact with great sensitivity to their situation, stay connected in whatever way you can that allows the family member or friend to know you are there but that is in service to their safety. In addition, to relieve family tensions more generally when possible go out for exercise or essential supplies alone, if able try not to be in the same room. For the abuser, the Respect phone (0808 8024040) may just be the life line that saves a life.

____________________

Jennifer Brown is co-director of the LSE’s Mannheim Centre, and was previously the Deputy chair of the Independent Police Commission looking into the future of policing.

Jennifer Brown is co-director of the LSE’s Mannheim Centre, and was previously the Deputy chair of the Independent Police Commission looking into the future of policing.

Terri Cole is Senior Lecturer In Forensic Psychology at Bournemouth University.

Terri Cole is Senior Lecturer In Forensic Psychology at Bournemouth University.

Yvonne Shell is Senior Clinical Teaching Fellow at the University of Portsmouth, and a Consultant Clinical and Forensic Psychologist working with offenders with identified mental health challenges.

Yvonne Shell is Senior Clinical Teaching Fellow at the University of Portsmouth, and a Consultant Clinical and Forensic Psychologist working with offenders with identified mental health challenges.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: by Dil on Unsplash.

1 Comments