As part of the LSE Festival 2023, the Mapping People and Change exhibition visualises data through maps on various socio-economic issues, providing insights into the impact of a rapidly changing world on people and communities. Researchers Andrew Eyles and Lee Elliot Major show how the chances of getting a degree have changed across three generations in different regions of England. Myung Jin takes a closer look.

Mapping People and Change is on display as part of the LSE Festival from 12 until 17 June 2023.

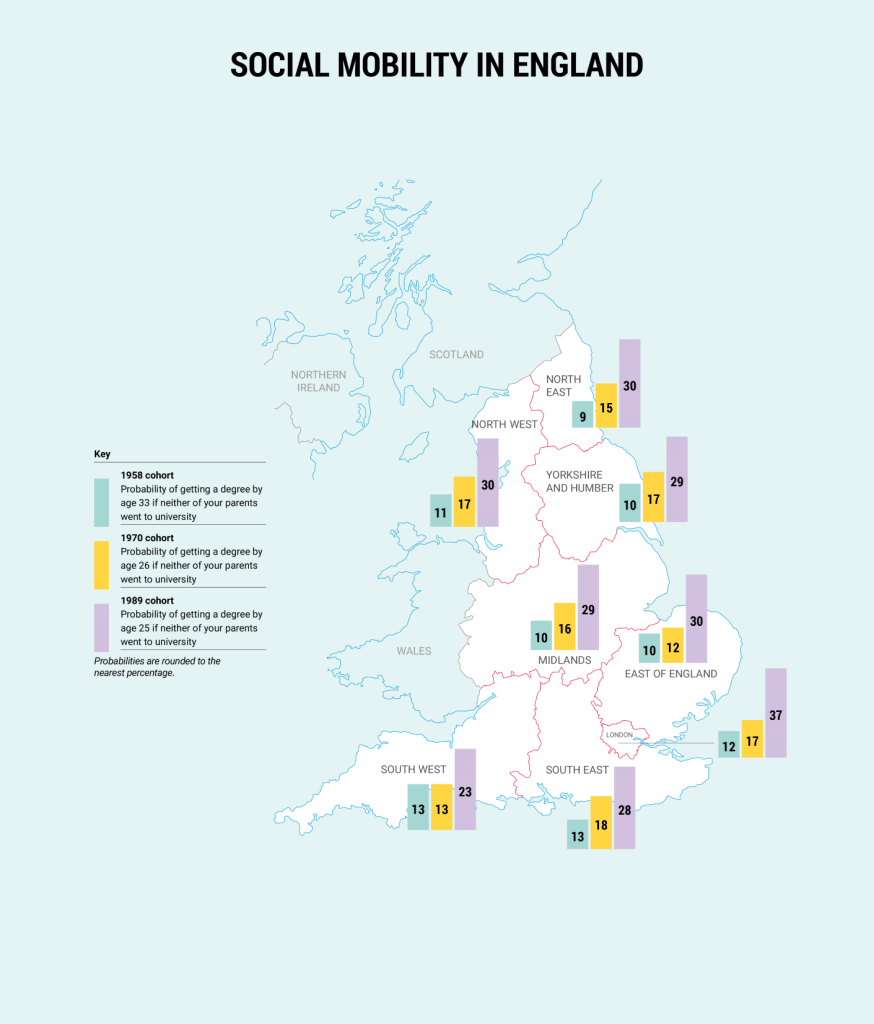

Social mobility refers to changes in a person’s socio-economic status compared to their parents (inter-generational mobility) or over their lifetime (intra-generational mobility). Measures like income, class and education are used to assess these changes. As part of the LSE Festival Mapping People and Change exhibition, our map – based on previous research – shows how the chances of getting a degree, if neither of your parents did, changes for people over time, across eight different regions of England. Outlined below are some of the key insights revealed.

- Graduation rates have improved over three decades – especially for those from non-graduate households

Our map shows that children born to non-graduate parents in 1989 were almost three times more likely to achieve a degree than those born in 1958 – graduation rates for those who were the first in their family to pursue higher education rose from 11 per cent to 30 per cent.

- Closing the gap

In 1970, about 50 per cent of children born to graduate parents could expect to get a degree, while only 16 per cent of children from non-graduate households had the same expectation. This gap narrowed significantly for those born in 1989: about 55 per cent of those born to graduate parents obtained a degree, while 30 per cent of children born to non-graduate households also obtained a degree.

- London’s success story…

Greater London has seen significant success in educational social mobility. For those born in London in 1958, the probability of getting a degree if neither parent had gone to university was 12 per cent. For those born in 1970, this rose to 17 per cent, and for those born in 1989, it had risen to 37 per cent – the highest of all regions in England. The change, between 1958 and 1989, in the chances of getting a degree if neither parent did was therefore greatest in London, with a 25 percentage points difference.

- …but the South West has fallen behind

In contrast, the probability of being the first in the family to get a degree in the South West, for those born in 1958, was 13 per cent. But for those born in 1989, this number was 23 per cent. The change in the likelihood of being the first in one’s family to obtain a degree was smallest in the South West, between 1958 and 1989.

- In the north of England

For those born in 1958 in the North East, fewer than one in 10 (9 per cent) were the first in their family to obtain a degree – the lowest in the whole of England at that time. By 1970, this had risen to 15 per cent and then to 30 per cent for those born in 1989. Only those from London had a higher chance of getting a degree.

Future outcomes

In 2022, around 368,000 people in England obtained a first degree. Comparing those born in 1958 to those born in 1989, the likelihood of obtaining a degree has increased in all the regions of England.

Improving intergenerational social mobility, and better access to education to achieve this, is important: obtaining a university degree increases the chance of employment and of higher earnings. In 2021, graduates earned a median salary that was £10,000 more than that of non-graduates, and the employment rate for working-age graduates stood at 86.7 per cent, while the rate for non-graduates was 70.2 per cent, according to the UK government.

Students from disadvantaged backgrounds often end up enrolling in lower quality institutions than they could have gone to.

But is simply getting students from poorer backgrounds into university enough? As Gill Wyness and colleagues argue, there is a need to focus on the type of universities and subjects chosen by students from disadvantaged backgrounds. They find that such students often end up enrolling in lower quality institutions than they could have gone to (based on their academic achievement) and end up earning less than those from richer backgrounds – ie, there is a “mismatch” between students and universities.

Students from more disadvantaged backgrounds who move away from home, appear to be as well-matched as similar attaining students from richer backgrounds. Considering this, the authors suggest that high-ranking universities could engage in outreach efforts to attract local disadvantaged students.

More research on social mobility from the Centre for Economic Performance can be found here.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main Image credit: Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay