The UK’s official e-petitions portal sees high levels of engagement. But does it really allow citizens to have a say in shaping policy? William Goodhind argues that, while petitions have the potential to mobilise public interest in e-Democracy, the platform’s potential is currently an untapped resource and reform is needed to capitalise on a community eager to have their voice heard.

Online petitions get a bad rap. Lumped under the faintly derogatory terms “clicktivism” and “slacktivism”, they are often portrayed as an ineffective tool for political agenda-setting. Academic research echoes this sentiment, albeit with an important nuance. Studies have found that, though petitions have a weak correlation with MP decision-making, they are nonetheless a remarkably popular means of democratic participation.

An uneasy paradox is therefore apparent – the pairing of vibrant societal engagement with only marginal, actual impact. However, it is perhaps a distraction to focus on the relative success of petition outcomes. Rather, we should be capitalising on their ability to pool, surge and catalyse public interest in government and parliament decision-making. This is where the UK’s official petitioning site needs to change. A redesign is long overdue to include greater user interaction and enrichment with contextual detail. Reform of this flagship e-Democracy platform is not about bolstering signature counts, but to harness the appetite of the “slacktivism”-hungry polity itself.

UK e-petitions – the sleeping giant

The UK government and parliament petition site is arguably the simplest and most accessible means of political expression. Since the site’s launch in 2015, it has proved a popular mechanism to crowdsource action, with close to 23 million signatures collected as of the 2019 general election. The rules are simple: after 10,000 signatures, the government will issue a response. At 100,000, a petition is put forward for debate by MPs.

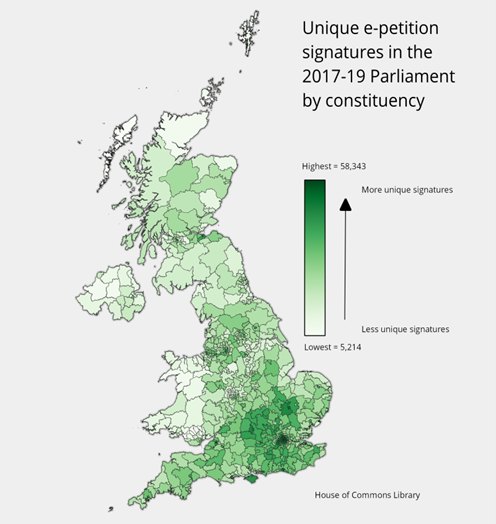

As a digital activism platform, the website has been a resounding success. Under the current parliament, there have been 817 responses issued and 161 petition debates held so far. These figures are a demonstrable shift in UK politics away from a predominantly representative democracy to a more inclusive, participative relationship. Aggregated into constituencies, the below graphic shows that signatories come from throughout the UK, albeit with a higher count in central and southern England.

This nationwide uptake occurs despite the consistently low conversion rate. Analysis of data from 2015-17 showed that, out of 10,950 e-petitions accepted by the website, only 4.5 per cent reached the requisite signatures for a government response. From the same cohort, 0.6 per cent achieved the 100,000 mark. For any would-be online activist, these odds make for sober reading. And it gets worse.

Even reaching these targets is not guaranteed to translate into meaningful change. Research suggests that petition outcome largely depends on contributing factors. An empirical study published in 2020 found that e-petitions were more likely to influence new MPs and MPs from marginal seats, who were more “sensitive to variation in constituent issue priorities.” By contrast, e-petitions have “essentially” no effect “for MPs who hold government or opposition frontbench positions.”

Separate interview research with a sample of 64 MPs found that only 23 per cent agreed e-petitions influenced government policymaking. As one respondent MP reflected: “Petitions act as a lightning conductor. They allow people to feel they’re having a say without actually committing government or individuals to any particular course of action. Therein lies the problem.” This raises the question of why, given the weak linkage between group effort and a discernible outcome, they remain a hive of public activity.

Research with a sample of 64 MPs found that only 23 per cent agreed e-petitions influenced government policymaking.

It boils down to citizen agency. E-petitioning’s underlying purpose is one of empowerment and it remains a bona fide and proven route to exert pressure, however minimal. The proliferation of social media outlets and usage has also spurred petition growth and changed the way in which people engage with politics. With the advent of Web 2.0, digital activism is pursued along a spectrum – from light-touch spectator endorsement (liking, sharing, reposting), through to pooled support (e-petitions, crowdfunding), and adversarial acts (data leaks, doxxing, hacking). For goal-oriented individuals and groups, the appeal is in the belief that sequenced, cumulative or concurrent activism, no matter how small their individual effect, can combine to build momentum on a bigger scale.

It is this desire for greater participation – and the big data it offers – that government and parliament should be capitalising on. A fundamental redesign of the petition website can help to set the UK’s approach to e-Democracy in the right direction.

Embracing Web 2.0

For a start, the site’s functionality is basic to the point of being restrictive. At the time of writing, over a thousand open petitions lie hidden in a sprawling digital archive. Petition statements are ranked by signature count on a conveyor belt of semi-static pages, introducing a self-reinforcing bias for those at the top, with no RSS feed, mailing list, or noticeboard for new entries. While the introduction of a forum or comments feature would be unwieldy, or else leave the site exposed to trolls and bots, an alert system tailored for public, media or civil society audiences is a feasible alternative.

Moreover, a user login capability – admittedly a more complex undertaking – would encourage longer-term participation in not just petitions, but calls for evidence, inquiries and bill development. At present, the Petitions Committee occasionally runs public surveys (five in 2022, four in 2021), but these activities are not published on the petition site, with obvious limitations for their catchment.

Next, there is a striking absence of contextual detail. Petitions are not thematically tagged, nor linked to relevant legislation, department(s), government reports or Select Committees. They are islands of isolated thought. The system lends itself to skin-deep protest statements primed for social media outrage. Indeed, academic and House of Commons research has shown that petitions imbued with emotive phrasing are more likely to succeed. Tagging and enriching petitions with metadata gives the enterprise greater credibility and nudges visitors towards an informed opinion. With the age of AI upon us, this is a problem that can easily be outsourced.

In their linguistic and semantic analysis of UK petition data from May 2015 to June 2017, University of Leeds researchers Lomax and Clark identified 21 distinct topics. They argue that, through machine-assisted learning, it is possible “to automatically and consistently categorise e-petitions”, with continued refinement over time.

Lastly, while there is the option to submit feedback on the site, evidence of a two-way conversation and promotion of petition successes is nowhere to be found. A reinvigorated and visibly present relationship between the Petition Committee, public and academia will help improve the quality of petitions, boost web traffic and stimulate multidisciplinary research. Meanwhile, publishing guidance on best practice, details of outreach events, and examples of real-world impact will enliven what is currently a staid, tight-lipped online presence.

The UK’s e-petition site is so much more than slack activism. It has literally millions of people contributing to issues that are capturing the national consciousness. We need to celebrate and inspire the public’s interest in politics and policy development. An overhaul of the e-petition system is a practical step than can transform the user experience into something more multilayered, accessible and interconnected. As a corollary, it may go some way to shift MP and government attitudes, and in doing so encourage a closer look at what people are willing to put their name to.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by MetsikGarden from Pixabay