There has been a striking link between falling voter turnout and declining confidence in politicians as a group. Sarah Birch advocates reforms designed to change popular engagement with politics, such as allowing 16 year-olds to vote, a more robust citizenship education programme, and making voting compulsory for first-time voters.

There has been a striking link between falling voter turnout and declining confidence in politicians as a group. Sarah Birch advocates reforms designed to change popular engagement with politics, such as allowing 16 year-olds to vote, a more robust citizenship education programme, and making voting compulsory for first-time voters.

Political inclusion is the essence of democracy. The ideal of inclusiveness is what distinguishes democracy from autocracy, although the institutions which translate the democratic ideal of inclusiveness into political reality have always worked imperfectly. These imperfections are a fact of political life. Democrats might reasonably expect that over time our institutions would be improved through innovation, technological advance and increasing levels of citizen education. What we have in fact witnessed in recent decades is a worrying deterioration of the ability of our political system to include all citizens in the decision-making process. This article aims to consider several possible reasons for this deterioration and assess potential antidotes to it.

Documenting and accounting for political exclusion

Falling from an average of about 80 per cent in the 1950s, turnout at general elections this century has hovered about the 60 per cent mark. More worrying still are trends in the composition of the electorate. Recent decades have witnessed two dramatic developments: the opening of a participation age gap and a wealth gap. The difference between age groups has grown from a gap of 18 percentage points between the 18–24 year-olds and the over-65 group in 1970 to a chasm of over 40 points between the same groups in 2005. The gap between turnout figures for the rich and the poor has also widened from seven percentage points between earners in the top income quartile and the bottom quartile in 1964 to 13 points between these groups in 2005.

Trends in electoral participation are complex phenomena and undoubtedly have multiple causes, but there has been a striking link between falling turnout and declining confidence in politicians as a group. Scholarly studies have found that citizens who are less trusting of politicians and more likely to view them as unethical are also less likely to vote. So what is it about the contemporary political class that repels so many people? Why is it that increasing numbers of citizens feel politicians do not represent the interests of people like them?

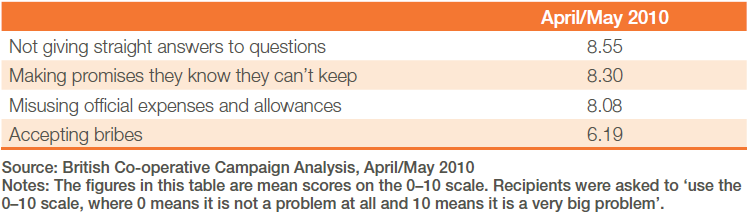

Research on this topic suggests that voters are put off mainly by politicians’ discursive manipulations, seen as a greater problem even than abuse of resources. While members of the UK public do get exercised about revelations of cash-for-questions or expenses fiddling, what really bothers them about politics is spin, weasel words and politicians not having the courage of their convictions.

Table 1: ‘How much of a problem is the following behaviour by elected politicians in Britain today?’

The composition of the UK political elite has also changed in recent years, with a documented rise in the number who come to parliament from occupations related to politics. The proportion coming into politics from manual professions has declined commensurately in recent decades and women and ethnic minorities remain poorly represented. Although it is debatable as to whether this makes politicians less able to perform their representative duties it is not surprising that there are growing numbers of people who feel that their interests are not adequately catered to by political elites and who therefore voluntarily withdraw from the political process.

What is the most appropriate way to solve this problem?

There is evidence that political inequality is intimately tied to social inequality, and that political engagement would be promoted by a roll-back of the dramatic increase in economic inequality that Britain has witnessed in recent decades. At the same time, this is a mammoth and politically contentious task. Despite the clear merits of policies designed to address inequality, they will be put to one side for the purposes of this analysis, which will focus on a range of more manageable and less politically fraught reforms that could be expected to have a short-term impact on political participation.

- A more robust citizenship education programme. A longitudinal study of citizenship education conducted by Avril Keating and colleagues finds that this element of the school curriculum can have a positive impact on political engagement and participation, but only when delivered with a certain intensity. Specifically, the effect of citizenship education depends on dedicated teachers and discrete timetabling for at least 45 minutes per week, as well as set examinations.

- Lower the voting age to 16. If people vote in the first election for which they are eligible, they are more likely to vote in later years. Lowering the voting age to the point where most people are still living at home and in education can also be expected to increase the chances that they will vote the first time they have the opportunity, as the institutions of the family and the school can be expected to be conducive to political participation. People aged 16 and 17 will be able to vote in the Scottish independence referendum of 2014, and this will provide a useful means of gauging the effectiveness of voting-age reduction.

- Make voting mandatory for first-time voters. So-called ‘compulsory voting’ rubs against the grain of many traditionally libertarian British instincts and it is difficult to envisage full-scale mandatory electoral participation receiving majority support. At the same time, there is a strong case to be made for the attractiveness of mandatory electoral participation for those new to the electorate. There are good reasons for believing that obliging young people to ‘try’ elections at least once would not be overly offensive to liberal sensibilities, and it could well have a dramatic impact on rates of electoral participation.

- Enforce compulsory electoral registration in the UK. In recent years, there has been a decline in rates of electoral registration (from 97.8 per cent in 1983 to 90.5 per cent in 2006) in tandem with falling turnout, and this drop has disproportionately affected young people. The Electoral Commission estimates that 56 per cent of 17–24-year-olds are not registered. Under the current regime, anyone failing to provide the electoral registration officer of a local authority with information requested can be fined up to £1,000, yet this penalty is imposed very sparingly in practice, and research by the Electoral Commission suggests that many people are not even aware that electoral registration is in fact mandatory. The Coalition government has decided to retain the compulsory element of electoral registration together with the penalty system, but the reforms fail to provide for more rigorous enforcement. It would also make sense to introduce new ways of checking registration details and registering to vote, including facilities located at libraries, post offices and other public places.

The changing role of political elites and parties

In addition to reforms designed to change popular engagement with politics, it makes sense to consider strategies for changing the object of engagement: the political class itself and the political system. This approach is based on the premise that disengagement by the electorate may be as much a symptom of a deeper problem as a problem in its own right. If this is true, then it makes sense to ask what might be done to change the way politics works.

The most challenging aspect of British politics that needs addressing is perhaps political discourse broadly conceived. For example, it is unlikely that any reform to our political institutions would be entirely successful in reducing spin and empty promises. Though desirable, such a shift in behaviour is unlikely to happen in the foreseeable future in the absence of a major political crisis.

There is one reform that might help to address the professionalisation of politics by shaping how people rise up in political life. The relative roles of talent and wealth in determining the success of an aspiring politician is something that has long been the object of debate, but the role of money in politics has become more evident in the wake of reforms that increased the transparency of campaign finance. There has for several years been broad agreement among the main parties that the system of party finance is ripe for reform, and that the fairest way forward is the introduction of public funding of parties, as happened in most western European democracies in the 1970s. Negotiations have foundered over the details of funding arrangements, but a well-designed public funding system could go a long way towards enhancing the perception of a ‘level playing field’ in politics.

It might also make sense, as part of any new public funding regime, to provide political parties with dedicated funds to identify, train and encourage people from groups that are traditionally under-represented in political life, including women, working class people, and ethnic minorities.

Conclusion

Political exclusion is a problem that is intimately tied to many aspects of political life. Although the challenges laid out here may seem daunting, there is reason to believe that several relatively modest but nevertheless decisive reforms to our social and political institutions could go a considerable way toward reviving declining levels of participation. If this challenge is to be addressed successfully, action needs to be taken on sooner rather than later. The longer participation falls, the less of a norm it will become, and the more difficult it will be to alter. Although there is currently a worrying trend toward opting out of electoral participation among the young, a significant majority of the British public still believe in the duty to vote. Now is the time to lock in this view through a series of changes to our institutions.

The full version of this essay appears in the book Democracy in Britain, essays in honour of James Cornford published by IPPR.

Note: This article was originally published on our sister site, the LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog, and gives the views of the author, and not the position of the General Election blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Sarah Birch is Professor of Comparative Politics at Glasgow University and a Fellow of the British Academy. She specialises in the study of ethics and misconduct. Her current research has two main foci: attitudes toward public ethics and electoral integrity.

Sarah Birch is Professor of Comparative Politics at Glasgow University and a Fellow of the British Academy. She specialises in the study of ethics and misconduct. Her current research has two main foci: attitudes toward public ethics and electoral integrity.