In this post, Jack Blumenau, Simon Hix, and Tony Travers argue that recent changes to the electoral registration process are likely to have significant consequences for the representation of students in the election in May.

In this post, Jack Blumenau, Simon Hix, and Tony Travers argue that recent changes to the electoral registration process are likely to have significant consequences for the representation of students in the election in May.

Last week saw the release of the latest electoral registration data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS). This release is particularly notable, as it includes the first indication of the effects of the introduction of the new Individual Electoral Registration (IER) protocol. Previously, one person was responsible for registering all voters in a given household. Since the introduction of the IER in June 2014, voters need to register individually either online or by post.

With the release of the ONS data it is now possible to assess the consequences of the move to IER. One key issue is whether the move to IER has reduced the number of people who are registered to vote. A second, and perhaps politically more important issues, is whether the reduction in registered voters is larger amongst some groups of voters than others. If this is the case, then some groups are likely to be under-represented in the election, which could favour one or more political party. Although it is often difficult to work out, a priori, what the distributional consequences of such changes are, the ONS data allow us to assess them.

The data released by the ONS gives the number of registered voters in each parliamentary constituency in the UK on the 1st December each year. In what follows, we compare the number of voters registered before and after the introduction of IER: 1st December 2014 compared to 1st December 2013.

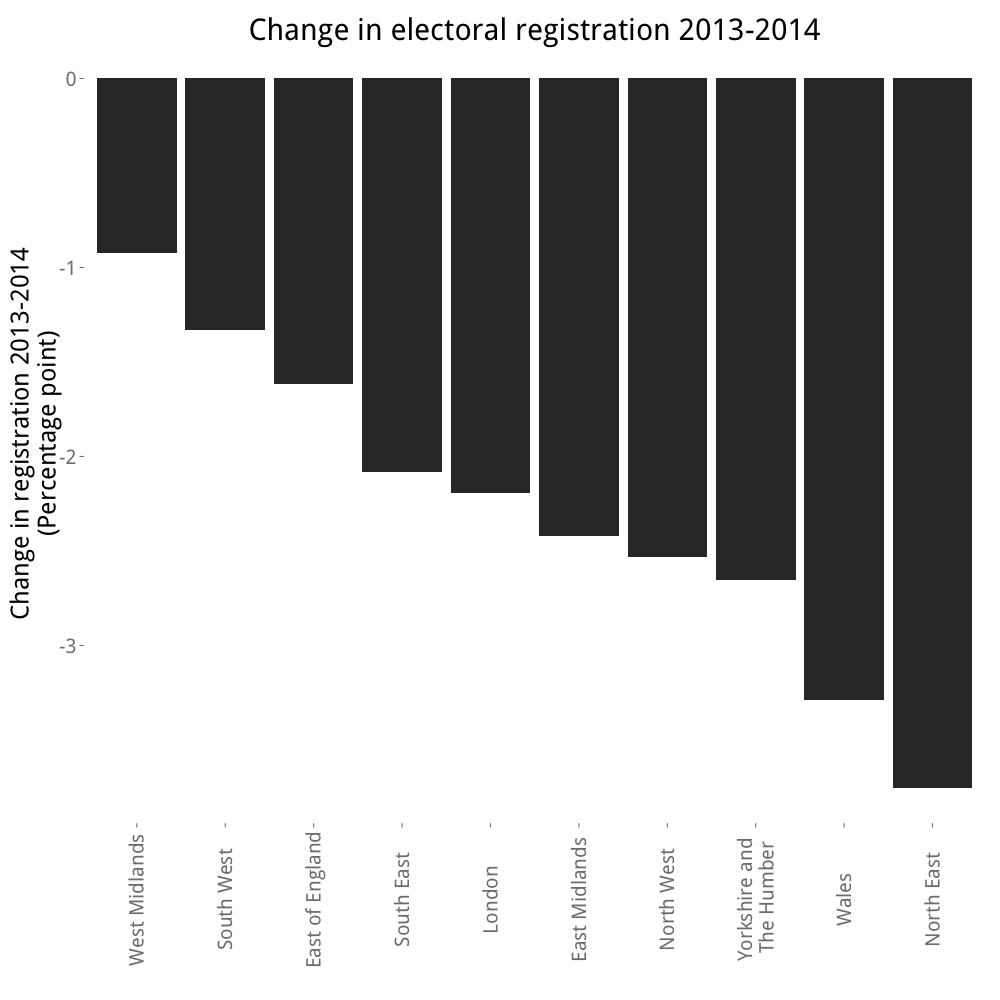

First off, the plot below suggests that, despite some regional variation, there has been a general decrease in the number of people registered to vote compared to 2013. From a normative perspective, registration rates matter. Most people agree that the democratic process is more legitimate when more people participate in elections. That registration rates have declined over the past year is therefore disturbing, particularly as there are only two months to go until the election, and only 48 days to go until the registration deadline.

Is there evidence that the decline in registration rates is non-uniform across social groups? In recent months, many commentators have suggested that the IER reforms are especially likely to affect university students. In January, Ed Miliband argued that the fact that students were likely to fall off the electoral roll was a “democratic scandal”. These concerns have focused on the fact that, in the past, universities have been able to register all eligible students who are living in university accommodation en masse. Under the new system, these students have to register individually.

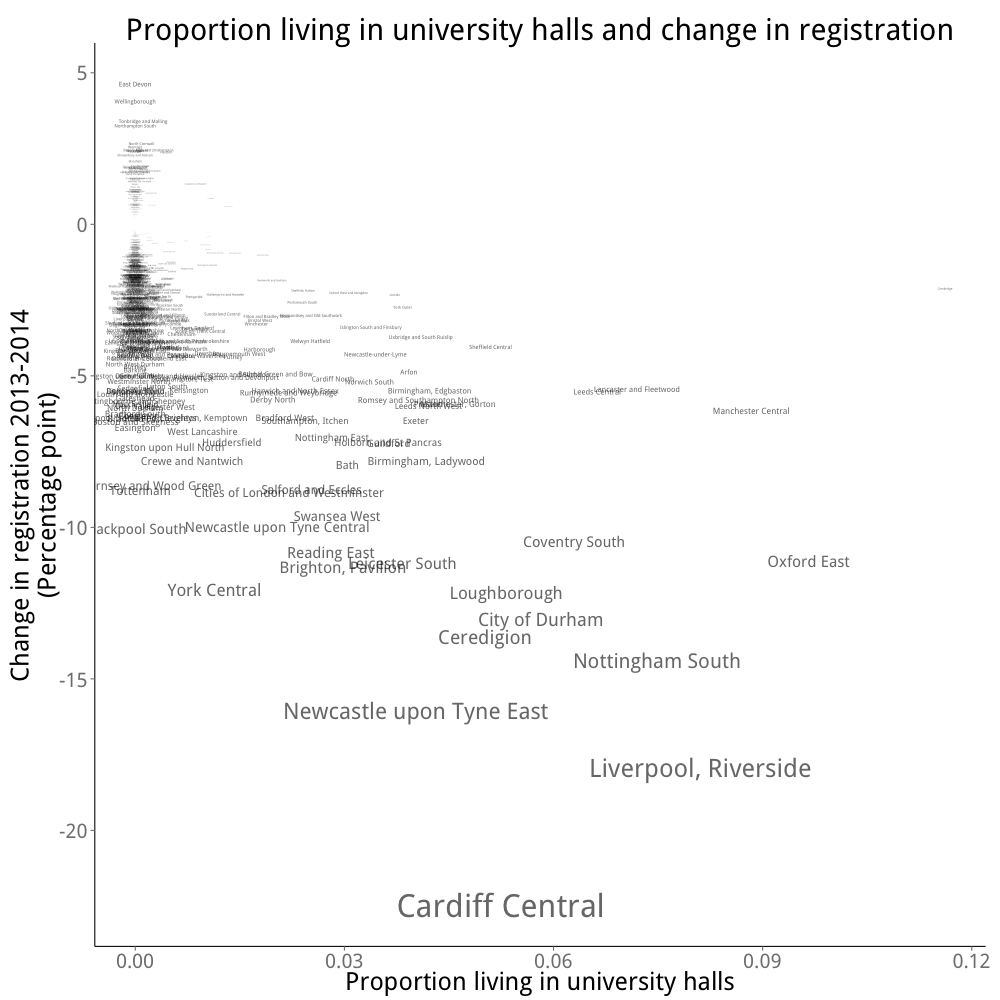

To investigate whether students have “fallen off” the electoral register the graph below plots the proportion of students in university accommodation in each constituency (on the x-axis), and the change in the registration rate from 2013 to 2014 (on the y-axis). Constituency names are plotted according to the absolute size of the change in registration over this period. While many constituencies have no students (those on the left of the plot), there are some big university towns and cities with many thousands of students living in university accommodation (those on the right).

The plot shows that the recent decline in registration rates is strongly associated with the proportion of students living in halls of residence in each constituency. None of the constituencies that have a significant proportion of students living in university accommodation have seen their registration rates increase, and several of them have experienced a sharp decline in registered voters. The decrease is particularly noticeable for some of our largest university towns and cities, including Cardiff, Nottingham, Newcastle, Oxford, Durham, Ceredigion, and Loughborough.

Furthermore, a number of important marginal seats feature in the plot above. The team at electionforecast.co.uk are currently predicting that Cardiff Central, Brighton Pavilion, and Loughborough are all likely to be decided by vote margins in the single digits. This means that small changes in the composition of the registered electorate might have large consequences in terms of electoral outcomes.

Of course, it is possible that this association is spurious. It may be that other factors, which also correlate with the proportion of students in a constituency, are driving this trend. As the Electoral Commission’s data only provides the aggregate registration rate in a constituency, and does not tell us whether those who registered are students or not, we cannot tell for certain whether it is students that are falling off of the electoral register.

Nevertheless, we are relatively confident in this relationship for two reasons. First, as noted above, the change to the registration process is particularly dramatic for students who live in university accommodation. The mechanical effect of the change from group registration to individual registration is simply more pronounced for those living in larger groups.

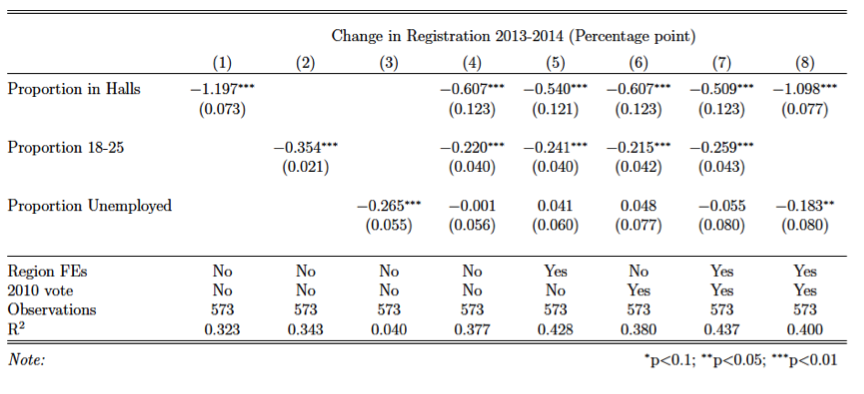

Second, further analysis (shown in the Appendix) suggests that, even when accounting for a whole host of alternative constituency characteristics, the proportion of people in living in university accommodation is a very powerful predictor of a decline in the registration rate in that constituency. The result is robust to controlling for the proportion of unemployed people, the proportion of young people, the region of the constituency, and the 2010 vote share of Labour, the Conservatives, the Liberal Democrats, the Greens and UKIP. The magnitude of the effect is also substantial: based on model 7 in the appendix, a 10 point increase in the proportion living in university accommodation is associated with a 5 point decrease in the percentage of voters registered.

This analysis has implications for party strategists in the coming weeks. Some parties would be well advised to encourage their potential student voters to register before the 16th April deadline. Students in the UK have traditionally voted for left, and centre-left parties such as Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens. Clearly, only students who are registered will be able to vote on 7th May, and so these parties have a strong incentive to raise awareness of this issue now. There is some evidence that this is already happening. Labour has employed a group of “General Election Student Vote Activators”, who will “maximize the number of students registered to vote”. These ‘Activators’ are likely to be strategically placed in key marginal seats where the student vote could be decisive.

A second implication relates to the efficacy of the IER policy itself. One of the stated aims of the IER is to increase the numbers of young people on the electoral roll. As the Cabinet Office’s guidance makes clear:

“Some groups have traditionally been under-registered, with just under half of … those aged 18 to 24 currently not on the register … Because we are now targeting people individually, everybody will be contacted directly, which will help maximise the number of people on the register.”

The findings here suggest that, at least in this respect, the IER has not achieved its declared objective. The number of student voters “missing” from the electoral roll in 2015 is large, and unlikely to change significantly in the next few weeks. In time, if citizens get into the habit of registering to vote at the age of 18, IER might increase registration amongst younger voters. In the short-term, however, the evidence suggests that the switch to IER may have disenfranchised students considerably.

Finally, our analysis also has implications for the representativeness of the political system. Changes to electoral registration rules have distributional consequences, unless their effects are uniform across the population. This is clearly not the case with IER. Working in a university means that we are naturally concerned that the preferences of students are properly represented at the ballot box, but the representation of students is likely to be disproportionately low in 2015.

Appendix: Linear regression analysis

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE general election blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Jack Blumenau is a PhD candidate in Government at the LSE.

Jack Blumenau is a PhD candidate in Government at the LSE.

Simon Hix is Professor of European and Comparative Politics and Head of the LSE Department of Government.

Simon Hix is Professor of European and Comparative Politics and Head of the LSE Department of Government.

Tony Travers is Director of LSE London, a research centre at the London School of Economics and Professor in the LSE’s Government Department.

Tony Travers is Director of LSE London, a research centre at the London School of Economics and Professor in the LSE’s Government Department.

Students can legally be registered at their home (permanent) address and term-time address – but only vote in one. Could this explain some of the reduction with fewer students being registered at their term-time address but still at home. They could still vote but not choose where their vote would have most impact.

I was just going to make the same point. When I chat to my own students, many prefer to have home residence pvs where they know the candidates, whereas they know little about the candidates here.