European Parliament elections may not have been popular, but they used proportional representation – something which England’s national elections lack. Heinz Brandenburg looks at what this means for smaller parties, which have a hard time making headway under the first-past-the-post system.

European Parliament elections may not have been popular, but they used proportional representation – something which England’s national elections lack. Heinz Brandenburg looks at what this means for smaller parties, which have a hard time making headway under the first-past-the-post system.

One of the few certainties about Brexit is that the UK will cease to participate in European Parliament elections. To many, this is perhaps the most inconsequential side effect of the UK leaving the European Union, since it means losing an election from the calendar that is arguable of minor importance and questionable democratic credentials, and that on average only a third of the voting population took part in. However, this overlooks the potentially game-changing implications of removing the only England-wide elections ever held under PR rules.

Interestingly, almost as a natural experiment, the European Parliament Act of 1999 replaced first-past-the-post (FPTP) with a closed party list system in England, Scotland and Wales at the same time as devolution introduced Welsh Assembly and Scottish Parliament elections. That means that PR was introduced in all three parts of Britain at the same time but with Scotland and Wales getting more of it, and, especially in the Scottish case, in arguably more important elections.

While PR is generally understood to facilitate multi-party politics, the consequences of introducing PR at a lower level in multi-level politics while sticking to plurality voting at the highest level remain uncharted territory. Now that some of this constitutional change is about to be revoked, partially for the others and entirely for one part of the UK, it is perhaps time to compare the impact of varying “PR-treatments” on multi-party politics.

Comparing party system fragmentation in Scotland and England after the 2015 general election, Patrick Dunleavy concluded that “the decline of two-party politics in the UK sounds the death knell for Duverger’s Law, with Britain now having a multi-party system akin to that which exists in other western European countries”. At face value, this is a somewhat exaggerated claim: despite considerable decline until 2015, the combined vote share of the two main parties in the UK has remained much larger than in European multi-party systems. However, the extent to which FPTP tempers fragmentation in general elections may hide how multi-party politics has taken hold in all parts of Britain. We need a different measure than vote shares in order to more effectively assess the extent to which voters in England, Scotland and Wales have embraced multi-party politics.

One of the characteristics of voting in multi-party systems is that individual voters often consider alternatives, although typically not from the entire supply but rather from a subset of competing parties. Vote choice becomes a two-step process: first, identifying the parties that one could consider voting for, and second, choosing one in a particular election. There are different ways to measure the size and composition of such consideration (or choice) sets at individual level – the few studies that pioneered this approach asked respondents in Swedenand Germany directly which parties they take into consideration when making their vote choice. Where such customised questions are not available, a very useful alternative exists in the propensity-to-vote (PTV) question, which asks “How likely is it that you would ever vote for each of the following parties?” to be answered on a 0-10 scale where zero means ‘very unlikely’ and 10 ‘very likely. This has been used in comparative research into consideration sets before and has been included in face-to-face Post-election Surveys and the Internet Panel of the British Election Study (BES) since 2014.

To measure consideration sets from PTV scores requires a meaningful cut-off for inclusion. An empirical cut-off emerges from the distribution of PTV scores that individuals give to the party they have just voted for. On average, across respondents from BES Post-election Surveys and the post-election waves of the BES Internet Panel (BESIP), we find that over 85% of a party’s voters rate that party seven or higher on PTV.

We are using BESIP because of its sample sizes, which allow comparison between England, Scotland and Wales. BESIP covers the EP elections and Scottish independence referendum in 2014, multiple waves around the general election of 2015, the EU referendum of 2016 and the general election of 2017. The great advantage of using panel data is that they reveal how party evaluations and thus consideration sets vary. Including only respondents who answered PTV questions in at least five waves, we find that less than 10% in each nation continuously have multiple parties in their consideration set, but vast majorities do consider more than one party over the lifetime of the panel – 74% in England, 79% in Scotland and 80% in Wales. Most of this expansion and contraction of consideration sets comes from parties dropping (often repeatedly) marginally in and out of consideration, and not from wholesale party switching.

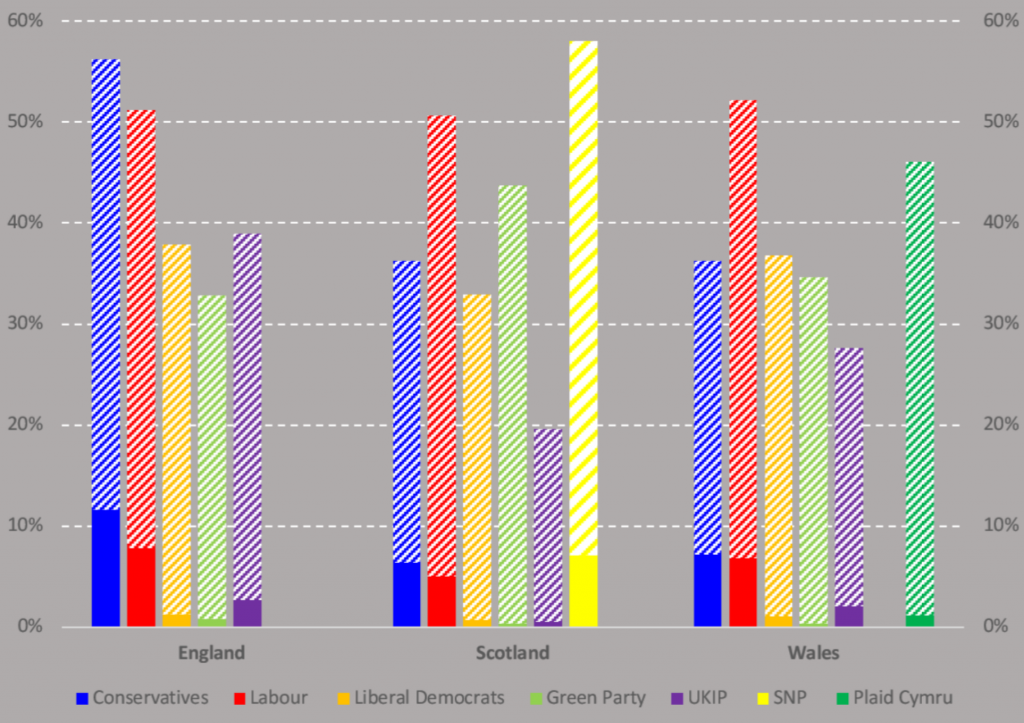

What this four-year panel study reveals is that each party in Britain has considerable electoral potential, but very little exclusive support. Figure 1 reports the total percentage of the population in each nation that has a party at some point in their consideration set, with the solid columns at the bottom indicating the percentage of the population for whom this is the only party ever coming into consideration. Conservatives and Labour in England, the SNP and Labour in Scotland, and Labour in Wales are the parties that feature in the consideration sets of over 50%. Apart from UKIP in Scotland and Wales, every party features in consideration sets of more than 30% of respondents. Plaid Cymru even makes it into the consideration sets of 46% of Welsh respondents.

Figure 1: Shared and exclusive electoral potential of parties in England, Scotland and Wales

Note: solid columns report per cent respondents who have only the party in question in their consideration set, patterned columns stacked above add respondents who have that party as well as at least one other in their consideration set. Source: British Election Study.

Note: solid columns report per cent respondents who have only the party in question in their consideration set, patterned columns stacked above add respondents who have that party as well as at least one other in their consideration set. Source: British Election Study.

Only the Conservatives in England are the exclusive inhabitants of consideration sets of more than 10% of respondents. Even the dominant SNP in Scotland has little exclusive support, only 7.2%. This may owe a lot to the Additional Members System used in Scottish Parliament elections, which actively encourages vote splitting. It is remarkable, then, that English voters have become just as likely to consider multiple parties as their counterparts in Scotland and Wales. Only a small minority (16%) have both major players (Labour and Conservatives) in their consideration sets, while over 70% of English respondents consider at least one minor party. It is difficult to see how even the forming of opinions about the range of small parties, let alone their consideration as potentially electable parties could have happened in England without the comparatively limited platform that EP elections have provided.

While the 2017 general election may have seemed like a return to two-party politics in England, with a combined Labour-Conservative vote share of over 80%, the panel data shows that consideration set size actually peaked in that election as it had also done in the 2015 general election. We are not yet living in a post-Brexit world; the major parties still have to rely on electoral context and system to deliver high vote and even higher seat shares. The disappearance of EP elections could make their lives a lot easier, though – even as their popularity plummets – by removing the only small platform afforded to minor parties in England. This makes it harder for voters to maintain meaningful opinions about small parties, and thus ultimately removes competition.

______________

This post was originally publised on LSE Brexit.

Heinz Brandenburg is Senior Lecturer in the School of Government and Public Policy at the University of Strathclyde. His research focuses on elections, party politics, political communication, and the impact of (un)representative party systems on satisfaction with democracy.

Heinz Brandenburg is Senior Lecturer in the School of Government and Public Policy at the University of Strathclyde. His research focuses on elections, party politics, political communication, and the impact of (un)representative party systems on satisfaction with democracy.

1 Comments