Thousands joined the SNP and Scottish Greens following the 2014 referendum, which they lost. Were these new members driven by an identification with the Yes movement? Lynn Bennie, James Mitchell, and Rob Johns explain how movement politics may have sparked a new type of party member.

Thousands joined the SNP and Scottish Greens following the 2014 referendum, which they lost. Were these new members driven by an identification with the Yes movement? Lynn Bennie, James Mitchell, and Rob Johns explain how movement politics may have sparked a new type of party member.

It seems that we are living in an age when any party, campaign or event is described as a movement. This often sounds odd given the strong associations between social movements, radical change, protest and dissent. Yet some movements are more modest in their demands. All involve a degree of collective action and a shared identity.

Connections between parties and movements are not new – parties exist within wider movements – but these links appear to be leading to surges in party membership. UK Labour has experienced a trebling of its membership, sparked by a leadership contest; and there has been mobilisation to new European movement-parties like Podemos in Spain and Italy’s Five Star Movement. However, there is no better example of the link between movements and party membership than the events surrounding the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence.

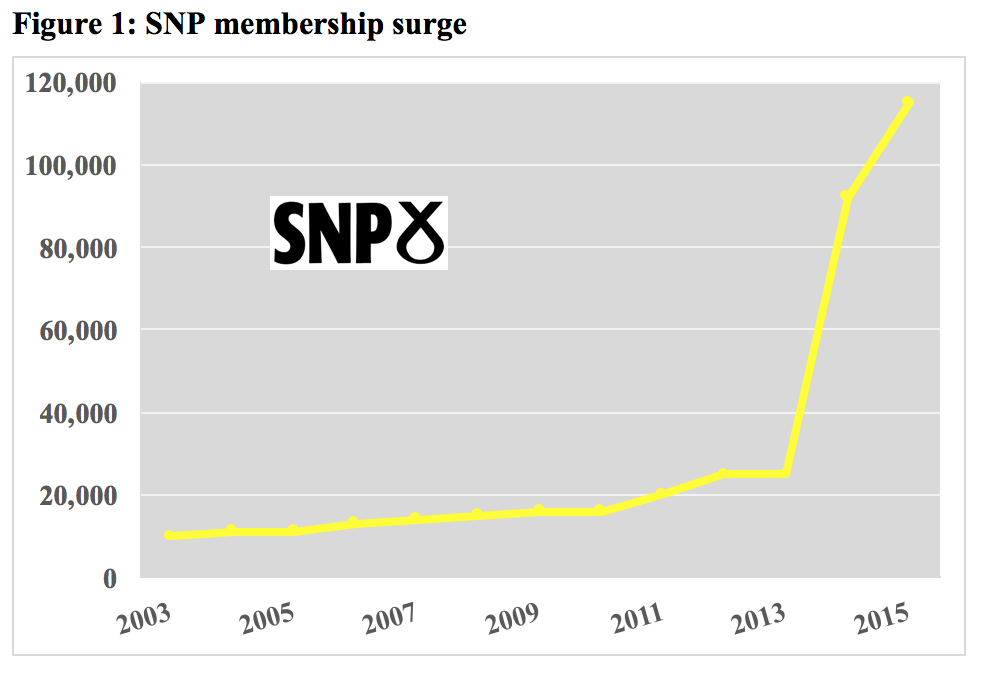

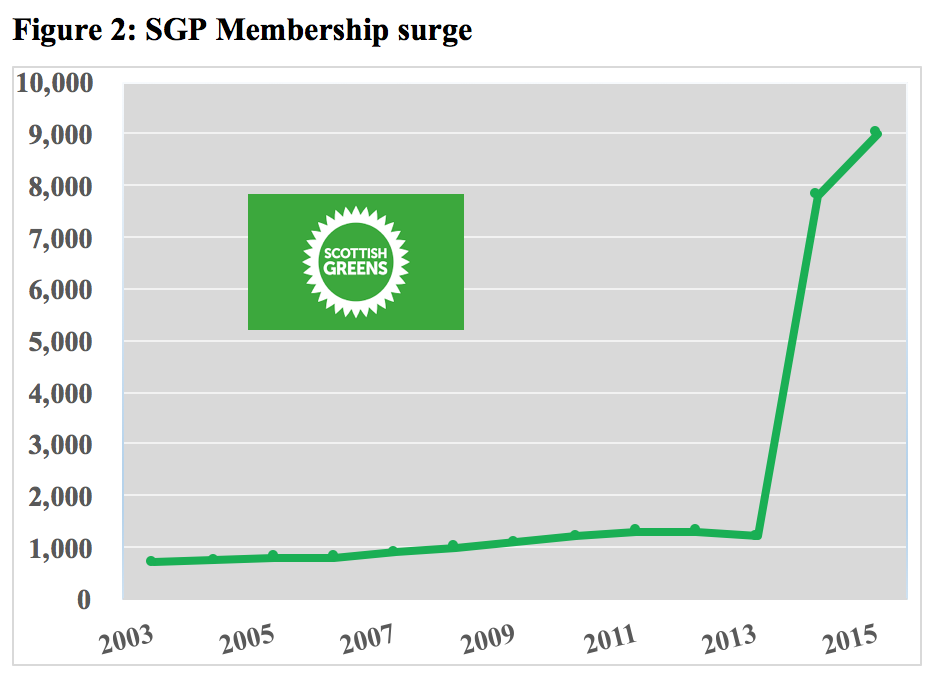

The referendum brought together campaigners with a common pro-independence purpose under the umbrella of Yes Scotland. The SNP’s vision of independence set the agenda but the grassroots and organic movement aspects came to the fore during the campaign. Party membership increased only modestly during the build-up to the referendum, but in the weeks after the result, the Yes-supporting parties experienced an unprecedented surge in recruitment (despite being on the losing side). Membership of the SNP and Greens increased five- and six-fold; they became parties largely made up of new recruits (Figures 1 and 2). Party membership was subsumed into the action repertoires of the Yes movement.

Our ESRC-funded study of the membership surges investigates why these events occurred. In simple terms, the dramatic increase was provoked by an event, aided by a bandwagon effect and conscious opportunism by the parties (especially SNP headquarters). But is there evidence to suggest that the new members were seeking to continue the movement politics of the referendum period? To what extent does being a party member feel like being part of a movement? Precisely how is group- or movement-based participation connected to the more conventional behaviour of party membership? Surveys of SNP and Scottish Green members which took place in 2016 allow us to compare the members’ backgrounds, motivations and experiences.

How, then, did this translate into party membership? Reported reasons for joining are diverse but focus on a belief in independence, social justice and, for the Greens, creating an alternative green society. There are signs of ‘movement joiners’ within both parties, with fairly large proportions agreeing that they ‘felt part of an exciting movement and wanted it to continue’, and the 2014 joiners are most likely to say so. As for how they behave within the parties, SNP members are most active, according to a range of measures of party involvement.

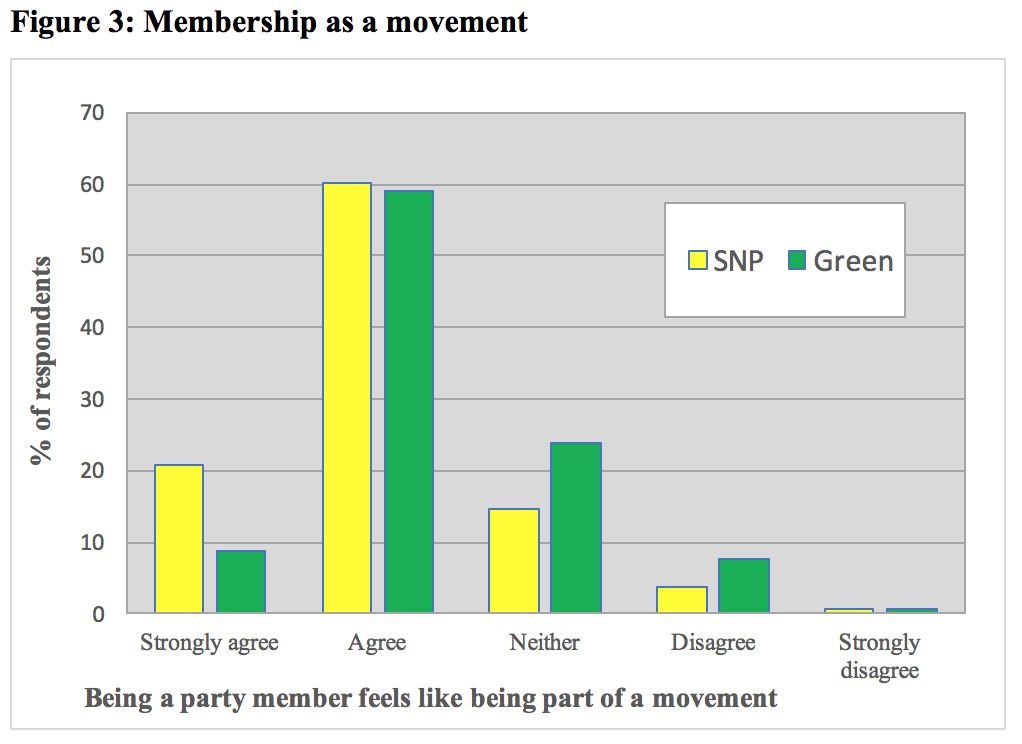

SNP members give the impression of being more committed to their party and to the independence movement. In turn, they are the most likely to see party membership as being part of a movement (Figure 3). Scottish Greens, on the other hand, display more varied identities and are a little less convinced that their party membership amounts to movement politics. They appear less comfortable as party members. It is perhaps no coincidence that the Greens have seen a reduction in members since the heady days of 2015, declining to 7,000 by the end of 2017, while SNP numbers continue to increase, the result of a series of mini-surges. Unfortunately, available data don’t allow accurate measurement of the numbers leaving or re-joining.

Finally, a comparison of joining cohorts reveals that new members (of both parties) are considerably less participative than established members (those who joined in advance of the surge). Movement politics may have sparked a new generation of members but they are less inclined to attend party meetings or help in core election activities like delivering leaflets. The result is an increase in activism within the parties, but a decline in the proportion of members who are active.

We may be seeing the emergence of a new type of member who is not very active, but neither are they completely passive, in that they are involved digitally in some way, preferring to participate at a distance from the party infrastructure. The members in this study report high levels of engagement with groups online, and, of course, most joined via an online platform. Approximately seven in every ten of all members say they use social media to talk about politics; and newer members are more likely to do this. Online participation is pivotal in the world of social movement politics and may be more appealing to movement-inspired members.

In conclusion, identification with the Yes movement existed, and it was a relevant factor in party mobilisation following the referendum, evoking the image of an ‘imagined community’ that exists in people’s minds, even if they never meet others in the movement. This suggests that when parties are connected to movements, there is capacity for (re)mobilisation to formal party membership. Feeling part of a movement, however, is not necessarily highly participatory, and it sits beside other political identities, especially in the Greens. Our evidence suggests that being a party member is not for everyone; it might be a fleeting experience for those who prefer the excitement of online protest and dissent. Moreover, parties can’t control bottom-up, movement forces – it is hard to recreate a grassroots campaign. Nevertheless, there is potential for parties to capitalise on their movement connections.

___________

Note: The data come from the Economic and Social Research Council-funded project Recruited by Referendum, Award Ref. RG13385-10. The authors are grateful for the Council’s support and the co-operation of the two parties in fielding the survey.

Lynn Bennie is Reader in Politics at the University of Aberdeen.

Lynn Bennie is Reader in Politics at the University of Aberdeen.

James Mitchell is Professor of Public Policy at the University of Edinburgh.

James Mitchell is Professor of Public Policy at the University of Edinburgh.

Rob Johns is Professor of Politics at the University of Essex.

Rob Johns is Professor of Politics at the University of Essex.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

I perceive a slight error in understanding in the article – almost at the end. where it concludes, “parties can’t control bottom-up, movement forces . While that statement is true the fact is that the SNP is a bottom up movement and has been so probably from its inception.

Party policies cannot be decided by branch or constituency officials or by the elected to government members.

Party policy can only be decided by delegates chosen by the grass-roots membership at branches and sent to National Conference and any member can propose a motion or an amendment to a motion and, if seconded, it must be recorded in the minutes of the branch meeting. It can, of course, have counter motions or amendments proposed.

In any event they are dealt with at branch level and may be debated and voted upon at branch level and passed on up the tree to eventually be dealt with at National Conference.

People may remember the change in SNP policy of NATO membership played out by conference on national TV..

It was not First Minister Alex Salmond that decided party policy but the delegates after debate and voting. Alex Salmond had but one vote as had every other card carrying party member. No other party is bottom up led.