What is at stake in the ongoing university strikes? To answer this question, Ewan McGaughey explains how the pension system works, who governs it, and their conflicts of interest. He argues that there is a need to rebuild the university and pension governance system so that it is more democratic and just. Otherwise the same issues will keep returning.

What is at stake in the ongoing university strikes? To answer this question, Ewan McGaughey explains how the pension system works, who governs it, and their conflicts of interest. He argues that there is a need to rebuild the university and pension governance system so that it is more democratic and just. Otherwise the same issues will keep returning.

We need justice in education. In the face of massive strikes and student protest, Universities UK proposes to change pensions from ‘DB’ to ‘DC’ plans. But what does this all really mean? My niche field of pension law and corporate governance has suddenly become cool with the university strike, so I’d like to (1) explain the issues in this strike in the simplest terms, (2) explain who governs our pensions and universities, and their conflicts of interest, and (3) what we can do about it. We must rebuild our university and pension governance system, so this never happens again.

What is the strike about?

In a ‘Defined Benefit’ (DB) scheme, your employer guarantees you income from retirement till death, based on your contributions. It doesn’t matter how long you’ll live. This is mostly what the university pension, USS, is now. In a ‘Defined Contribution’ (DC) scheme, you get money on your retirement. But if you live longer than you expect, that could run out. If you live fewer years than you expect, your family could inherit what is left over. Universities UK has a new plan to make all pensions ‘DC’. We should call these what they are: ‘Die Quickly’ (DQ) pensions. You’re better off not living into old age, when money runs out. DC means DQ.

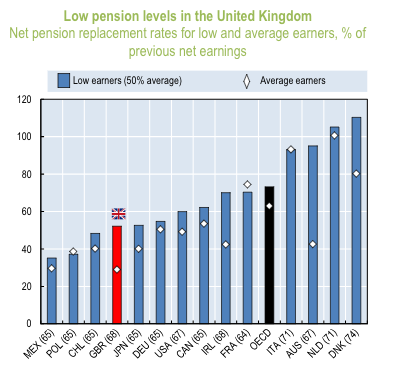

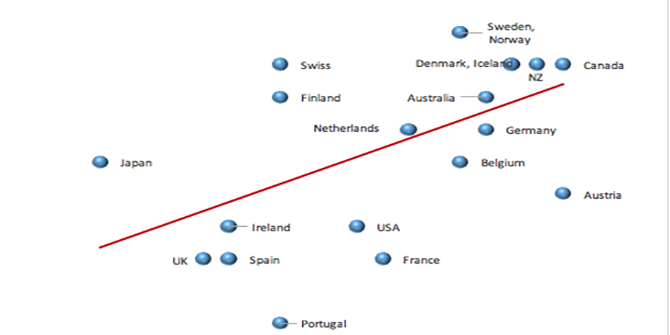

The university employers, UUK (the university Vice Chancellors), argue people are living longer, and so DB pensions are unsustainable. What they don’t say is the UK has among the worst pension systems in the world because DB schemes have been shutdown. Successful pension systems have public DB schemes, where the state pension guarantees you an income for life.

Source: OECD, Pensions at a Glance 2017.

Source: OECD, Pensions at a Glance 2017.

Supported by valuations of USS managers, the employers argue spiralling payments are needed to maintain pension benefits as they are. What they don’t say is they reach this result through ‘mark to market accounting’, which faces huge criticism. USS puts everyone’s contributions together and invests in the stock market, corporate bonds, government bonds, derivatives, and funds of funds. Those asset values go up and down with the market. ‘Mark to market accounting’ means accounts show that market volatility. An alternative is ‘smoothing’ of values, to average out market volatility. This could be better, but pension funds should have decade long investment strategies, not think in short 3 year terms.

What USS has done is picked a point (31 March 2017) when asset prices happened to be low as proof there is a massive pension deficit. UUK now says “defined benefit pensions are unsustainable!” What they don’t say is that employers took pension ‘holidays’ (not paying into your pension) when asset prices were high between 1997 and 2009. One reason asset prices have tanked in the short-term is the economy is being destroyed with, and since, the Brexit poll.

Who governs our pensions?

It gets worse. The board of USS is packed with ‘co-opted’ directors (5 of them) who hold the balance of power between employer representatives (4) and staff or union representatives (3). Currently, the co-opted USS directors are four previous asset managers, and one mining manager: from JP Morgan, Warburg Pincus, Old Mutual, Schroders, and Rio Tinto. Asset managers in the US and UK have for 30 years pushed for all DB pensions to close, to become DC/DQ schemes. For instance, Arnold Schwarzenegger tried to ‘terminate’ the California teachers retirement scheme in 2005, but he lost after mass opposition. Asset managers and certain politicians want this because they can make more fees. If you retire, and you have a lump of cash, but you don’t know how long you will live, the asset managers can help you (for a fee). They can sell you an annuity, to give you income as long as you live (for a fee).

Asset manager fees are uncontrolled. If you have an average pension for 40 years, a 1.5% yearly asset management fee sucks 35% of your pension savings into the pockets of the City. Even a 0.5% fee destroys 13% of your pension. If we get DC/DQ pensions, we will be sold these annuity ‘services’ just like the mafia sells protection. If you don’t buy an annuity, you’d better Die Quickly. But if you do buy an annuity, you will be poor, and beholden to City asset managers. Unlike a well-managed USS, those asset managers selling you annuities really might go bankrupt, leaving nothing: like Equitable Life or Barlow Clowes did.

This is why it matters that asset managers are packed onto the USS board. However friendly and outgoing they are as individuals, they are a lobby group for destroying DB pensions. But it gets worse still. If you read into the USS annual reports (I encourage, but don’t recommend it!) you find that USS is now paying its fund managers as a whole 482% in 2017 (p.15) of their bill in 2008 (p.103). Total USS operating costs are 186% today of the price 10 years ago.

So why haven’t the university Vice-Chancellors done anything about it? If university employers are on the hook, why haven’t they reformed USS? The answer is they do not have any incentive to care. As Adam Smith said in The Wealth of Nations, they control ‘other people’s money… Negligence and profusion, therefore, must always prevail’. Always, unless there is accountability in university governance.

University Vice-Chancellors are often friendly, politician-type figures, but the systems to hold them accountable are seriously defective. For example, Dame Glynis Breakwell was the Vice Chancellor of Bath until forced to announce resignation in November 2017. She was paid £468,000 a year. And guess what? UUK put her on the USS board. Even if Vice Chancellors don’t directly set their own pay, people they can appoint, influence, or work with, do. Staff and students get votes for the governing body in many universities. But these systems lack transparency, and need to improve a lot.

What we can do: students and staff

So we need three big changes. First, in every university, staff, the University and College Union, and students should demand every governing body has a majority elected by staff and students. Many universities do this, but the systems need to be transparent and universal. To give just two examples, at Cambridge University the 25 person Council has 16 staff seats, 3 student seats, and 6 seats for university managers. But although the Council is bound by fellows’ votes, staff seats are weighted by seniority, and many part-time, fixed-term, and administrative staff are excluded from voting. At King’s College, London the Charter and Statutes requires a 21 member Council, with 12 lay members, 8 staff, 1 student. But there is no provision for actual elections of staff representatives, and they should not be in a minority. When managers are unaccountable there is negligence and profusion. UCU stopped the abolition of staff representation in 2011. It is likely that UCU members will organise and push forward.

Second, we need to make pension governance accountable. USS is a big, multi-employer pension plan. It should eliminate inflated costs, and take asset management and corporate voting completely in-house. Nobody on its board should have possible conflicts of interest from their professional background: that includes asset managers like JP Morgan, and mining corporations like Rio Tinto. The most successful pension fund is the Church of England scheme, which has done what the asset management industry said was impossible: it made money with ethical investment, and is divesting from fossil fuels. UCU should get a majority of staff representatives on the pension board, and conduct direct elections for USS members. This will strengthen USS and UCU by engaging staff in union and pension policy. When people have a stake and a voice, they will not let go. They are the experts. They will not let anything like this happen again.

Third, education must be accessible based on merit, and that means free, funded by progressive tax, not regressive debt. In this strike, students are not fooled by attempts to divide them from staff. They know the same management that is cutting pensions supported rising tuition fees. Sir Andrew Cubie chaired the ‘Joint Negotiating Committee’ behind USS, and used his casting vote to order that DB pensions are scrapped. In 2000 Sir Andrew wrote a report favouring tuition fees in Scotland (but paid through a graduate tax), and has recently been advocating austerity. Younger academics, like me, were the original targets for this experiment in higher fees, not higher education. We are the same as students. We oppose kleptocratic, conflicted, incompetent administration. We want democracy and justice in education.

______

Further reading:

* L Hannah, Inventing Retirement: The development of occupational pensions in Britain (CUP 1986).

* E McGaughey, ‘Votes at work in Britain: Shareholder monopolisation and the single channel’ (2018) Industrial Law Journal (on votes at work, including at universities, summarised on the LSE British Politics Blog).

* E McGaughey, ‘Member Nominated Trustees and Corporate Governance’ (2013) Speech to the AMNT (explaining elected pension trustee history and potential voice in corporate governance).

* E McGaughey, Participation in Corporate Governance (PhD 2014) ch 6 (on the history of occupational pensions in the UK, Germany, and US).

* E McGaughey, ‘Does Corporate Governance Exclude the Ultimate Investor?’ (2016) 16(1) Journal of Corporate Law Studies 221 (on asset manager conflicts, summarised on the Oxford Business Law Blog).

Ewan McGaughey (@ewanmcg) is a Lecturer in Private Law at King’s College, London and a Research Associate at the Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge. He did his PhD at the London School of Economics, on the seemingly boring topic of pension law, asset management, and corporate governance.

Ewan McGaughey (@ewanmcg) is a Lecturer in Private Law at King’s College, London and a Research Associate at the Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge. He did his PhD at the London School of Economics, on the seemingly boring topic of pension law, asset management, and corporate governance.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

You nailed it! Thank you.

Hon Wai, you are a very, very long way off the mark in terms of the numbers in 2). I am a lecturer at a Russell Group university and, like many, a “late entrant” – I’m 40 now and have been in the job only a couple of years having spent many years as a student / clinical intern (that’s 12k a year – I’m a veterinary surgeon) in order to get where I am now.

The 45k figure you give for my annual pension in retirement is just preposterous. For a start, it’s more than my salary. I’m not complaining about that at all – I love my job and my salary is good – but I will never, ever earn 110k. The top of our academic salary spine (top of “grade 10”) is 100k. To put it into context, I’m at the top of grade 8. Most academic staff won’t get anywhere near a 100k salary, ever, unless they climb the management pole.

The pension I’d receive under the current scheme will be approx 18k annually. The pension I’ll receive under the new proposals will be approx £7800 annually. I used USS and UCU pensions modellers to get to these figures, not the back of an envelope.

@TB:

“The 45k figure you give for my annual pension in retirement is just preposterous. For a start, it’s more than my salary. I’m not complaining about that at all – I love my job and my salary is good – but I will never, ever earn 110k. The top of our academic salary spine (top of “grade 10”) is 100k. To put it into context, I’m at the top of grade 8. Most academic staff won’t get anywhere near a 100k salary, ever, unless they climb the management pole.”

The 45K I gave is based on the assumptions used by UCU to generate the headline figure that junior staff will be £10K worse off a year:

https://www.ucu.org.uk/article/9093/Overhaul-of-university-pensions-could-leave-staff-200000-worse-off-in-retirement

This headline grabbing figure is calculated by UCU for lecturers who “Starts on £39,992 and moves up pay spine to £110,217” (see Table 1). If you think this scenario is “just preposterous”, then complain to UCU for using unrealistic scenarios in its publicity war.

It’s great to hear you love your job and you feel your current salary is good. The academics I know also love their job and are dedicated to their research. I think UK’s world-class academics are poorly paid, relative to their exceptional skillset. I hope a solution can be found soon to resolve the dispute, stop further damage to reputation of UK universities, students won’t lose out, universities can continue providing a generous pension without cutting on staff numbers and research spending and facilities.

Hello Hon Wai,

Thanks for your reply. The headline figure of 10k a year works even for lower salaries and lower pensions – hence, mine would go from between 10 and 20 to less than 10. As I say, there are plenty of modellers that work this out – here’s one:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/mqjqo5urzzrtjxl/modeller_nmd_180220.xlsx?dl=1

and it’s worth bearing in mind that they make rather generous assumptions, such as a 2% annual pay increase (hahaha). The USS “deficit” has, of course, calculated based on our annual *4%* pay increase (hahahahahahahaha). The 200k figure is based upon that average 10k and the length of an average retirement before one pops one’s clogs (i.e. 20 years).

Yes, of course any lecturer *could* move up the pay spine from 100k over that period or time and if so yes, they’ll build up more – but as I say, the overwhelming majority will not (that’s just one of the tens of possible “staff profiles” that were tested). UCU doesn’t just represent lecturers, for a start, but many academic-related staff, and increasingly academic staff are employed on contracts without any prospects for progression, despite their skill set (people with PhDs and postdoctoral contracts as “teaching fellows” for example – there is no prospect of promotion for most of these jobs, so they’re stuck at grade 6/7 for life). On a 1/75 accrual with 55k DB cap as we sit currently I’m still not sure how you work out the 45k. Either way, it’s a massively bum deal and based on discredited premises.

Anyway, thank you for your supportive words. I do love my job, though I hate what marketisation is doing to it – I don’t what I do to make people rich or to satisfy the wants and ambitions of avaricious people, so it’s becoming increasingly difficult to work in HE. I care deeply for my students and feel like a mother wrenched from her children. I want to get back to them asap and so yes, I hope that a reasonable solution can be found too, and quickly.

Thanks TB for the modeller spreadsheet and your concern for your students.

According to USS 2017 report (p.106), the assumed salary increase is RPI+1%. Ever since the financial crisis in 2008, salaries in private and public sector had experienced an unprecedented stagnation in real wage growth. It is reasonable to assume wage growth will resume a more normal trajectory in the coming decades, making RPI+1% (RPI is currently 2.7%) a reasonable estimate.

I know the scenario of current salary of £40K rising to £110K at retirement is highly atypical. For publicity purpose, UCU based their headline grabbing figure of £10Kpa worse off under the new scheme on this scenario. Other more plausible scenarios shown in the tables I pointed earlier show smaller reductions.

The modelling spreadsheet you attached assumes pensioners will buy an annuity. This will inevitably show a significant reduction in pension payout compared to DB scheme, because annuity rates currently are very low, for the same (main) reason UK DB schemes in aggregate show a huge deficit of around £460bn – namely, long-term 20-year interest rates are currently near record lows (https://www.ftadviser.com/pensions/2017/09/01/uk-pension-deficit-soars-to-460bn/). Most commentators agree that interest rates are artificially low due to Bank of England and other central banks’ quantitative easing measures. So by the time people currently in their 40s retire, annuities should give better payouts. Nonetheless, for the same interest rate and same level of employer+employee contributions, annuities will always provide significantly less pension payout than DB scheme, because life insurers have to factor in risk around the different parameters, charge a premium for taking on these risks, charge investment management fees, on top of a profit margin for creating annuity products. DC schemes can offer a higher average payout and eliminate longevity risk (the “Die Quickly” drawback discussed in McGaughey’s article) by pooling the assets and liabilities across all employees, something along the lines of the collective DC (CDC) scheme recently agreed between Royal Mail and CWU (https://www.professionalpensions.com/professional-pensions/news/3025820/royal-mail-and-cwu-agree-to-introduce-uks-first-cdc-scheme). A CDC can take an investment horizon much longer than an individual can, hence can remain invested in high-return high-risk assets, thereby delivering a higher expected payout. A CDC is like a DB, with the investment risk transferred from the employer to employees collectively. (see Michael Otsuka 2016 on how they work, along with defence against philosophical objections, eprints.lse.ac.uk/66309/1/Otsuka_RiskofLivingtooLong_14Nov2016_Final%20V1.pdf; also, https://medium.com/@mikeotsuka/how-uk-university-employers-could-greatly-improve-their-uss-pension-offer-at-no-cost-to-them-1fd970844bcc). Something like a CDC may have to feature in the final solution to the dispute.

Hon Wai, there are two things I don’t understand about your comment.

I think the proposed changes to the USS only see the employers contributing 13.25% into a DC fund. I’m basing this on https://www.uss.co.uk/how-uss-is-run/valuation/2017-valuation-updates/proposed-changes-to-future-uss-benefits. Have I got this right?

Secondly it is a matter of record that UUK reduced pensions contributions from 1997 is it not? This is what I understand is meant by a pension holiday. I can’t understand why you would need to know whether the fund was in deficit to decide whether the pension holiday had occurred, unless the phrase pension holiday has some technical meaning I’m unaware of. This letter sent by Imperial UCU seems to make it very clear that contributions were reduced in 1997: https://mobile.twitter.com/ImperialUCU/status/966761806789267457. Can you explain?

@John A

You wrote: ” there are two things I don’t understand about your comment.I think the proposed changes to the USS only see the employers contributing 13.25% into a DC fund.”

I did find the 13.25% figure odd when I read it in an article by USS, which points out under the proposed DC scheme, 13.25% out of the 18% total employer contribution goes directly into member’s funds:

https://www.uss.co.uk/how-uss-is-run/valuation/2017-valuation-updates/proposed-changes-to-future-uss-benefits

This would imply 4.75% is taken up with running costs, which is unreasonably expensive for a pension fund. I used this figure for purpose of doing a back of the envelope calculation to see how much annual pension payout one would get under DC. For DB scheme, costs should be viewed as a percentage of the fund’s assets, which work out to be 0.2% (a very reasonable figure). For the proposed DC scheme, it is unclear to me how costs would be apportioned. If 4.75% of contributions are eaten up by costs under the proposed DC, then this fact alone means USS members are much worse off. However, I have not read any UCU article highlighting excessive costs of the new scheme, so maybe this is not the right way to understand the 18% and 13.25% figures. If you can dig up some explanation of the 4.75%, I would be interested to know.

“Secondly it is a matter of record that UUK reduced pensions contributions from 1997 is it not? ”

Yes, they reduced contributions to 14% in 1997. “Pension holiday” as defined in Ewan McGaughey’s article is “not paying into your pension”. This is also the standard definition, though the term

is sometimes used loosely when contributions continue to be paid but at a reduced rate (see Institute of Actuaries glossary https://www.actuaries.org.uk/documents/pensions-glossary-terms). By this definition, UUK never took a pension holiday. My earlier comment was to point out the factual error in the article saying they did. I don’t know whether USS was in surplus from 1997 to the early 2000s. If it was, and if the actuarial valuation justified it, then one could argue based in the circumstances at that time (e.g. life expectancy lower than current estimates, high long-term bond yields, expected return on assets), it was a prudent decision to make. Of course, UUK is not excused from the responsibility of putting things right, if for decades, they had given the impression to their employees that the DB scheme would run in perpetuity.

On the “missing” 4.75%: the explanation given here http://www.uss.co.uk/how-uss-is-run/valuation/2017-valuation-updates/proposed-changes-to-future-uss-benefits is that in addition to costs it is made up of deficit recovery contributions (for previously accrued liabilities, so it is disingenuous to include this in a claim about contributions to pensions going forwards) and death-in-service/ill health benefits.

I can answer this – the 4.75% is a contribution to the deficit reduction fund. ie it is paid by the employer into the pot to fund the previously guaranteed DB pensions of those already in the scheme.

Regarding operating costs, p16 shows that a) personnel costs have increased because more management is being done in-house, and b) investment cost have dropped over the last few years as a %age of funds. In addition, extra personnel have been needed to comply with increased regulatory requirements. Total on p15 (125m) doesn’t seem excessive for a 60bn fund, particularly as that includes the pension administration itself.

None of that of course excludes excessive pay, but curbing pay will make an insignificant difference to the fund.

All costs, staff costs included, should be reassessed in light of the tripling of student tuition fees in the past few years.

The head of USS (with his 17% pay rise last year) did a presentation to staff at my University. He clearly stated that there was not a deficit problem with the pension, there was a problem with the prices of the investments that he could make now to pay out later not guaranteeing big enough pay-outs to cover the required pensions. In other words, pensions per se are a bust flush in the current economic climate.

This could have been a lot better.

Unanticipated increases in life expectancy do not explain why USS has an unexpected deficit. If only. At a talk that Mercer gave at my university, they said that the life expectancies of USS members had actually not risen as much as had been anticipated.

It is asserted that defined contributions pensions systems are worse in the long-term, but without any real proof. Australia’s “superannuation” pension system is defined contribution with a mandatory element and does quite well. What is unusual about the British pensions system is the idea of a contributions holiday. The reason that pensions holidays arose seems to have been that Dominic Lawson back in the 1980s raided DB pensions that seemed at the time to be overfunded. After that, British pensions funds never built up enough fat during the good years to see them through the lean ones.

Ethical investing is lauded, but how is this to be defined. Before the 2008 crash, there were many ‘ethical’ funds that refused to invest in pharmaceuticals but were fine investing in banking, at a time when banks were engaging in what turned out to be highly unethical practices.

There is very little sense in the debate overall (above and BTL) about who the big losers will be. Hon Wai talks about life expectancy overall, but this is very different for women and men and between individuals.The big losers will be people relying on the USS’s survivor’s pension.

What nonsense. Of course DB is better, you can rely on it until death. Would you really prefer a finite money purchase? On average they provide a stream of benefits half that of DB pensions, according to actuaries. But that is not really the worst point – they provide finite benefits, so “die quickly” is exactly right.

@Nick, @Chris

For the same level of annual employer contribution under DB and DC schemes, DB schemes certainly have benefit of addressing longevity risk in a way that standard DC schemes cannot (but DC schemes pooled across all employees can; though I don’t know the feasibility of implementing this scheme). Most people are at least slightly risk-averse, especially having enough money to live through retirement, so DBs offer a real benefit. (for benefits of DB, see this analysis by LSE’s Prof. Nicholas Barr: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/statistics/staff/academic-research/hutton/uss/barr__reform_directions_uss_150326.pdf). Under DB, employers assume most of the risks (risk that investment returns are below par; risk of unanticipated increase in life expectancy; risk of falling long-term bond yields; inflation risk). Under DC, employees assume all of these risks.

As to your (presumably rhetorical) question, “Would [anyone] really prefer a finite money purchase?” the answer is YES! In the past few years, there have been a surge in number of people in the private sector transferring out of their accrued DB schemes into DC scheme, because of a number of factors including the record low long-term interest rates, and apparently generous conversion factors. The well-known Financial Times commentator, Martin Wolf, has advocated transferring out of DB into DC (see https://www.ft.com/content/68dce2ce-c6a5-11e6-9043-7e34c07b46ef). For example, someone aged 45yrs with accrued DB benefits entitling them say £10K of real-value annual pension payout on retirement aged 60yrs, will get a cash-equivalent from the pension trustees of about £400K, which they would then put into a DC scheme. Would you accept £10K for life on retirement, or would you take your chances with £400K now which you invest yourself? There is no simple answer, as it depends on lots of factors including individual risk preference, how long one intends to work till retirement, expected asset returns, how much other savings and pensions (including state pension which is similar to DB in payout structure) and property equity (which can be released by downsizing to smaller house in retirement), personal circumstances (DBs typically have a 50% spousal pension in event of one dying during retirement leaving spouse behind; if the spouse also has own pension then the utility of having spousal pension is less; if one is single, then a cash-equivalent transfer into DC will be effectively generous because the transfer value factors in the loss of spousal pension), whether one wants to take out a lump sum on retirement offered by DC but not available under DB. It is true that DBs cover life, but the other side of the same coin is if one dies before the average life expectancy (currently predicted by some at about 92yrs for women, 85yrs for men; this gender discrepancy means DC schemes favour men), one loses much of the benefits one has accrued. If one died at retirement age, under DB, one would lose most of the benefits one spent a lifetime accruing (dependents will still get a modest lump sum). DC schemes allow the pensioner to bequeath remaining pension pot, use lump to repay outstanding mortgage, move to more expensive house. So a lot depends on one’s expected circumstances (very hard to estimate decades ahead of time) and one’s attitude to risk. If one is a high-earner (academics’ salaries are significantly higher than the average for population), one would have accrued other savings and assets for retirement, hence one is more capable of handling longevity risk.

@Chris

See page 106 of the 2017 USS report for the changes in actuarial assumptions used to estimate future value of assets and liabilities:

https://www.uss.co.uk/~/media/document-libraries/uss/how-uss-is-run/reports-and-accounts/2017-report-and-accounts-scheme.pdf

There are no changes to the mortality rates. The primary change since the 2014 valuation compared to the 2017 is a reduction of expected investment return from around 5% to 3% over a 20-year horizon. UCU disputes USS’ valuation of the fund, arguing 3% is too conservative, tilted too heavily towards the current historic low gilt yield (a very common, probably universal, practice across all UK DB schemes to calculate present value of future liabilities based on a long-term discount rate), and insisting USS should use a higher figure closer to the expected rate of return of the fund’s current asset mix.

Regarding Nigel Lawson “raiding” pensions in the 1980s, companies took contribution holidays because the government decided to tax any extra assets over 5% above their estimated liabilities. They were thought to be hiding assets away in the pension funds to avoid paying corporation tax. Gordon Brown as Chancellor also raided pensions from 1997, by removing the tax relief on dividend income from pension funds. The cumulative effect from 1997 to 2014 was around £120bn (compare against total deficit of all UK DB schemes as of August 2017 of around £460bn; see https://www.ftadviser.com/pensions/2017/09/01/uk-pension-deficit-soars-to-460bn/).

Problems with DB schemes came to light by the turn of the century. See the list of factors which led to demise of DB schemes in the private sector in UK, identified by Ros Altmann back in 2003:

http://www.rosaltmann.com/whathashappened/

Problems with USS came to light early on this decade, especially by 2014 when there were terse exchanges between USS and UCU:

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/statistics/staff/academic-research/hutton/uss/

For details of dispute over actuarial assumptions used to calculate the deficit, see:

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/statistics/staff/academic-research/hutton/uss/ussreplysssj.pdf

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/statistics/staff/academic-research/hutton/uss/replyceo.pdf

Well said Hon Wai! Just to clarify one point- the Pensions Regulator requires a valuation every three years, so the previous dates were 2014, 2011, etc. USS were very lucky to miss the market lows of March 2003 and 2009.

As we’ve seen, the stockmarket does have occasional 50% drops. In spring 2017 it was relatively high. What will happen at the next valuation if the liabilities are still 72Bn, assets dropped to 30Bn ? Worth thinking about for those who claim there is no deficit.

I do find it weird, and shameful really, that you can get a PhD at a high-status British uni without knowing much about pension finance which is all in the public domain.

I should apologise for being insulting but I feel insulted myself, having learned so much more merely by being an employee in the private sector who had to do the calculations — before the Internet supplied much help — as part of a collective enterprise for all of us who had been faced with chopices about coping with a DC scheme.

Although you have blanked my first comment, I’ll persist.

I spent decades working for a private company, whose DB scheme had staff members alongside management.

Those of us with experience gained in-work passed our expertise up to our staff rep there. The returns were , alas, good enough for the company to take a pensions holiday!

When the DB scheme was closed, all DC members are individualised, so advice is not feasible, although some IFAs speciualise in pensions and we knew the best.

Incidentally I was under the impression their fees were capped by Osborne a few years ago.

It’s true that the Uni bosses have cherry-picked a short span to “estimate” the viability of their scheme, and you’re right to call this out.

Meanwhile, it remains true that UK state pensions are relatively poor, yet their long-term sustainability is a big problem. Are there national comparisons which help explain how other countries manage this — or are they all kicking an exploding can down the road?

A curate’s egg of an article. The problems with DC schemes is that they transfer most of the risk to individuals and away from employers, so the payout is highly uncertain. DB schemes are therefore worth preserving. There are valid points about taking a long term view of valuations, greater diversity in governance, and exorbitant management fees. Much less impressive is the idea that this is all a plot by the asset management industry.The linkage to tuition fees is both fanciful and irrelevant. The economy has not been “destroyed” though it will indeed under-perform for many years as a consequence of Brexit. University governance is sometimes wanting, but to describe it as “kleptocratic, conflicted, incompetent administration” is unjustified and unhelpful in securing the changes the author advocates. Finally, the demographic pressures on all pension schemes are not illusory and therefore it is likely that some change will be required to the current DB scheme. It would have been helpful if the author could have offered some proposals for reform.

First off, a DC scheme need not be DQ. You used to buy an annuity with it, but as gilt yields fell, that is less popular. You can now invest in other income-producing asset classes where the capital stays untouched. (You can also take some or all of the capital: it’s your choice.)

Now I’ll return to the rest of the article.

Odd that you mentioned the Pensions Regulator none times in an article about governance.

I am in favour of academics at UK’s world-class universities getting better remuneration not less. However, there seems to be a number of factual errors in the article:

The author says employers took pension holidays when asset prices were high between 1997 and 2009. His analysis seems to be 2 decades out of date. At the turn of the century, many private employers were already closing their DB schemes to new members, and subsequent pension contributions for existing employees went into DC schemes. The factors to rapid closure of DBs starting in the early 2000s were rising lifespan factored into actuarial valuations, the deep stock market bear market following the bursting of technology bubble, persistent declines in long-term interest rates around the world starting from the mid-1990s. Between 1997 and 2009 as long-term rates declines, it put pressure on DB deficits, most UK DBs schemes were in deficit. It is most implausible university employers were permitted to take pension payment holidays when pension funds were in deficit.

“What USS has done is picked a point (31 March 2017) when asset prices happened to below as proof there is a massive pension deficit.”

This is entirely in line with established actuarial practice of doing a valuation of pension funds every couple of years on a fixed date. It may well be true this actuarial practice deserves much criticism, but one can hardly lay the blame on USS. Let’s suppose actuarial valuations are done every 4 years. I suspect the 2013 and 2009 valuations also show a massive pension deficit. The 2017 valuation may have reported an even larger deficit, but it has nothing to be “low” asset prices as the author claimed, but record high long-term bond prices hence record low UK 20-year gilt yields in March 2017. High bond prices (hence low bond yields) increase value of pension liabilities, by increasing the present value of future liabilities. Ever since early 2009, the two main types of financial assets pension funds invest in – equities and bonds – had enjoyed a phenomenal bull run.

“One reason asset prices have tanked in the short-term is the economy is being destroyed with, and since, the Brexit poll.”

This is nonsense. Whatever the adverse impact on the British economy due to the Brexit poll, after the initial plummet in stock markets, UK and world equities enjoyed a tremendous upward since from July 2016 to March 2017. Trump’s election also boosted world equities in anticipation of his proposed tax reform. UK bond prices also were higher during the 9 months following Brexit poll. Again, the adverse impact from Brexit on the financial assets wasn’t that asset prices tanked, but long-term yields dropped, which worsen pension deficits.

“Asset manager fees are uncontrolled. If you have an average pension for 40 years, a 1.5% yearly asset management fee sucks 35% of your pension savings into the pockets of the City. Even a 0.5% fee destroys 13% of your pension. If we get DC/DQ pensions, we will be sold these annuity ‘services’ just like the mafia sells protection”

I am not a fan of asset management fees at all. Throughout my career, I always avoided putting my pension under asset managers who charge the exorbitant 1.5% fees. The fee for passive management, especially via corporate DC pension schemes, should be closer to 0.2% which is reasonable. I would imagine USS can negotiate with fund managers so that university employees can enjoy a lower fee under DC scheme.

“If you don’t buy an annuity, you’d better Die Quickly.”

If the DC pension pot value at retirement is adequate, it will cover the expected lifespan. For academics working a full working life in academia, and employers contributing pension worth 20% of salary, they will most certainly have built up adequate pension under DC on retirement to retire comfortably up to the expected retirement age.

“Unlike a well-managed USS, those asset managers selling you annuities really might go bankrupt, leaving nothing”

This is a fair point about risk of annuities, though one should ask whether the risk of an annuity provider (don’t they have reinsurance schemes so that in event of a life insurer going bankrupt, its pension customers would be compensated?) going bankrupt is higher than USS going bankrupt. If USS doesn’t tackle its pension deficit, or if it adopts optimistic projections as the author seemed to be suggesting (instead of the conservative estimates), then it may well go bankrupt if long-term interest rates stay low and asset prices suffer below expected returns over coming decades.

“It should eliminate inflated costs, and take asset management in-house.”

Is there evidence in-house asset management schemes incur less cost than outsourcing to asset managers? The author thinks even 0.5% pa management fees will eat away at the pension fund. An in-house asset management will have to pay its staff salaries comparable to active managers in private asset management firms, in order to attract competent fund managers.

“The most successful pension fund is the Church of England scheme, which has done what the asset management industry said was impossible: it made money with ethical investment, and is divesting from fossil fuels.”

Ethical investment has been a feature of fund management industry for decades. Ethical funds are not fundamentally different from other funds. It is primarily a matter restricting the universe of assets the fund can invest in. There is no reason why avoiding tobacco companies, defence companies, say, and tilting towards technology and utilities companies (these should typically qualify as ethical investments) would generate inferior returns.

The author is being selective with data: Church of England scheme achieved stellar returns in 2016/17. One year does not make for being the most successful pension fund. Moreover, it is misleading to judge quality of pension fund based on return on its assets, just as it is also the case when judging asset managers. Risk, volatility, different horizons etc. also need to be taken into account. The author should present evidence that in-house asset managers achieve better risk-adjusted returns than private managers.

“Third, education must be accessible based on merit, and that means free, funded by progressive tax, not regressive debt.”

Whatever one’s view on funding of UK higher education, this point is irrelevant to USS pension dispute, as it concerns government policy, which is not a party to the pension dispute. If anything, abolition of UK tuition fees will mean restricting number of university places (see evidence on entry to Scottish universities), thereby reversing the expansion of UK universities over the past 2 decades (this surely will have adverse effect on university finances), unless offset by increased fees or numbers from international students.

@HonWai

It’s you who hasn’t got all their facts right. May I suggest doing some more research before accusing others of inaccuracy willy-nilly?

– University employers do not put in 20%, as you claim. Until 1997, they contributed 18.55% but this was reduced to 14%, and then went up to 18% in 2011. Still pretty good compared to the private sector but one has to consider that wages in HE are low given the level of qualifications required.

– Especially younger university staff who have done the calculations have consistently found that they are required to retire on an annual income that I wouldn’t regard as “comfortable”, ca. £10,000. For a lifetime of public service that does not seem right. You can see some individual examples on twitter – those folks are angry but they’re so for a reason.

– “It is most implausible university employers were permitted to take pension payment holidays when pension funds were in deficit.”

In fact the employers did take a contributions holiday, back in 1997.

The exact facts are actually hard to come by. Universities UK, the employers’ organisation is not subject to Freedom of Information requests. There is currently a petition open to change that. Then we’d all know more. Given how important universities are to the UK economy, this would be very desirable!

@KR

Hi Mate, you have not read carefully my comments nor the public information concerning the pension scheme. Let me respond to your criticisms:

1] “University employers do not put in 20%, as you claim. Until 1997, they contributed 18.55% but this was reduced to 14%, and then went up to 18% in 2011. Still pretty good compared to the private sector but one has to consider that wages in HE are low given the level of qualifications required.”

I quoted 20% as a round number, a close approximation to support my argument. My citation of 20% instead of the precise figure of 18.55% does not alter my analysis at all, which seeks to refute McGaughey’s claim that USS took pension holidays (i.e. the employer paying 0% contributions) during 1997-2009. Your own figures also refute McGaughey’s claim. Under DB schemes, employer contributions will fluctuate depending on the size of the pension deficit (few DB schemes in existence are in surplus for the reasons I outlined in my earlier post) – paying less when the deficit is smaller. Suppose USS’ employer contributions averaged 16% over the past 2 decades, this was still pretty generous compared to pension schemes in the private sector, a point you acknowledged. My own preference (no doubt, most university employees have different views on what should be done) is that UUK moves to a DC scheme (or some pooled DC scheme to address problem of longevity risk inherent with standard DC schemes), and compensate academics in increased salaries.

I agree that wages in UK’s world-class universities (I would not generalise my positive appraisal to the post-1992 universities) are low relative to the academics’ exceptional skillset. Please reread the opening sentence of my original comment, which I reiterate and then elaborate: I am in favour of academics at UK’s world-class universities getting better remuneration not less. I think UK’s world-class academics should have remuneration comparable with world-class academics in other countries, in order to attract the best from around the world.

2] “younger university staff who have done the calculations have consistently found that they are required to retire on an annual income that I wouldn’t regard as “comfortable”, ca. £10,000. For a lifetime of public service that does not seem right.”

You misread the £10K figure, which concerns how much younger staff will be off worse under the new scheme, not their pension payout. May I recommend that you follow your own advice of “doing some research before accusing others of inaccuracy willy-nilly”? See UCU’s article: https://www.ucu.org.uk/article/9093/Overhaul-of-university-pensions-could-leave-staff-200000-worse-off-in-retirement

The £10K figure is calculated by UCU on pension income of DB scheme compared to the DC for lecturers starting on £40K and moves up pay spine to £110K, working 30yrs before retirement (see the UCU article for further details). For this group, under the proposed DC scheme, based on my back of the envelope calculation (30yrs paying into USS, 27yrs retirement, linear wage increases, 5%pa real return on pension assets during working life, 2%pa real return during retirement, 8% members contribution, 18% employer contribution, minus 4.75%pa cost of running pension scheme), the yearly real-value pension would be around £45K – not great but enough to retire comfortably, especially when supplemented by the full state pension. There is of course a big unknown over asset returns over the coming decades. This is an inherent feature of all pension schemes reliant on investment returns, and the big question is who should bear this risk. Of top of my head, I recall the current DB scheme assumes 5% real return. If the actual return turns out to be less, then USS will end up with an even bigger deficit. As is well-known, the drawback with a standard DC scheme is the prospect of the pensioner living a long life (my calculations assume working continuously from age 35yrs to 65yrs, living till 92yrs), so the issue isn’t just a matter of comparable expected payouts between the current and proposed scheme.

I argued “Between 1997 and 2009 as long-term rates declines, it put pressure on DB deficits, most UK DBs schemes were in deficit. It is most implausible university employers were permitted to take pension payment holidays when pension funds were in deficit.”

You responded: “In fact the employers did take a contributions holiday, back in 1997. The exact facts are actually hard to come by.”

And was USS in deficit in 1997? If you do not know whether it was – as implied by your observation that exact facts are hard to come by, how does your response in any way refute my argument?

On checking the literature, I just picked up another factual error in McGaughey’s article: USS already manage its pension assets in-house.