The Conservatives under Boris Johnson have pledged to ‘level-up’ struggling areas of the country, particularly in the North. Lawrence McKay shows a widespread concern with this divide, but a shared belief that the current government is biased against these areas, acutely felt by Northerners in particular. The thin and vague policy agenda represented by ‘levelling up’ may not address this severe trust gap.

The Conservatives under Boris Johnson have pledged to ‘level-up’ struggling areas of the country, particularly in the North. Lawrence McKay shows a widespread concern with this divide, but a shared belief that the current government is biased against these areas, acutely felt by Northerners in particular. The thin and vague policy agenda represented by ‘levelling up’ may not address this severe trust gap.

A lynchpin of the Conservative reinvention under Boris Johnson and Theresa May has been its commitment to ‘levelling-up’. In the Prime Minister’s grand terms, his mission is to ‘answer at last the plea of the forgotten people’ living in left-behind towns and regions of the country, namely in the North of England, and ‘restore trust in our democracy’. Survey research, predating the current government, has established a marked trust gap between regions and between rich and poor areas in the UK, perhaps linked to a sense of biases in government policy-making. At the very least, an agenda that explicitly centres such places offers some hope for closing this trust gap. However, our analysis shows that the ‘forgotten people’ feel as forgotten as ever: indeed, the current government is seen as actively biased against them.

‘Levelling up’ has often been treated as an open goal for the Conservatives, and perhaps for good reason. The Johnson government is in many respects blessed with a favourable environment for the levelling-up project. Economically, the costs of borrowing to invest are currently minimal. Politically, there is a broad coalition across parties and within the Conservative Party in support of the goal of rebalancing, a stark contrast to (for example) Italy and Spain, where politicians in richer regions have often resisted sending their tax revenues for spending elsewhere. However, our survey results reveal the hidden political risks to the government, reinforcing the suggestion from other polls that we are seeing the first cracks in the Red Wall.

Between 11 and 18 December 2020, we ran an online survey of 1,476 UK adults with Ipsos MORI. We started with a series of questions about how much government cares for your area, as compared to other parts of the country. These are more useful than previous survey questions, as they convey an active sense of bias rather than more general dislike or distrust in governments. We asked how much people agreed or disagreed with the statement ‘the government cares less about people in my area than people in other parts of the country’.

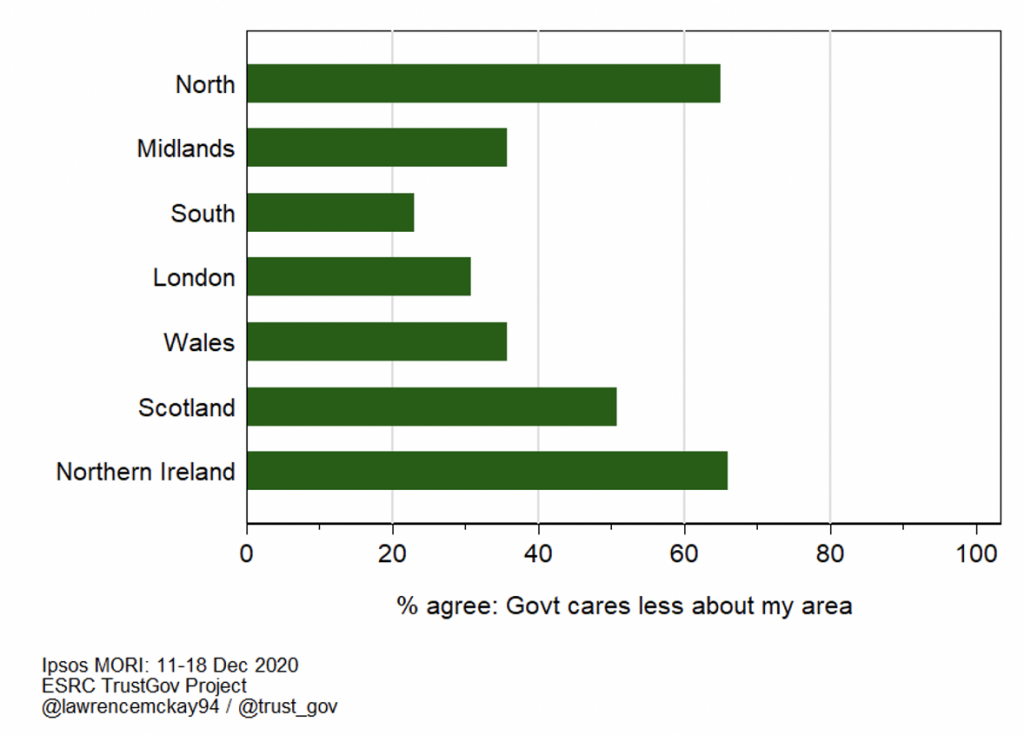

Nationwide, roughly two in five people endorse this view. However, when broken down by region, as seen in the graph below, a stark pattern reveals itself. In the North of England, nearly two-in-three believed that the government cared less, falling to 36% in the Midlands, 31% in London and 23% in the Southern regions outside London. Furthermore, given a 7-point scale, Northerners chose the most extreme ‘strongly agree’ option over any other option, indicating the intensity of their discontent. Even among a small sample of Northern Conservative supporters, people agreed with the statement by 45-30. These beliefs do not simply reflect a consistent trust or distrust in government. Londoners, for example, were just as likely (at 27%) to say that they ‘almost never’ trusted government. Rather, this specific and focused grievance is layered on top of pervasive and general discontent.

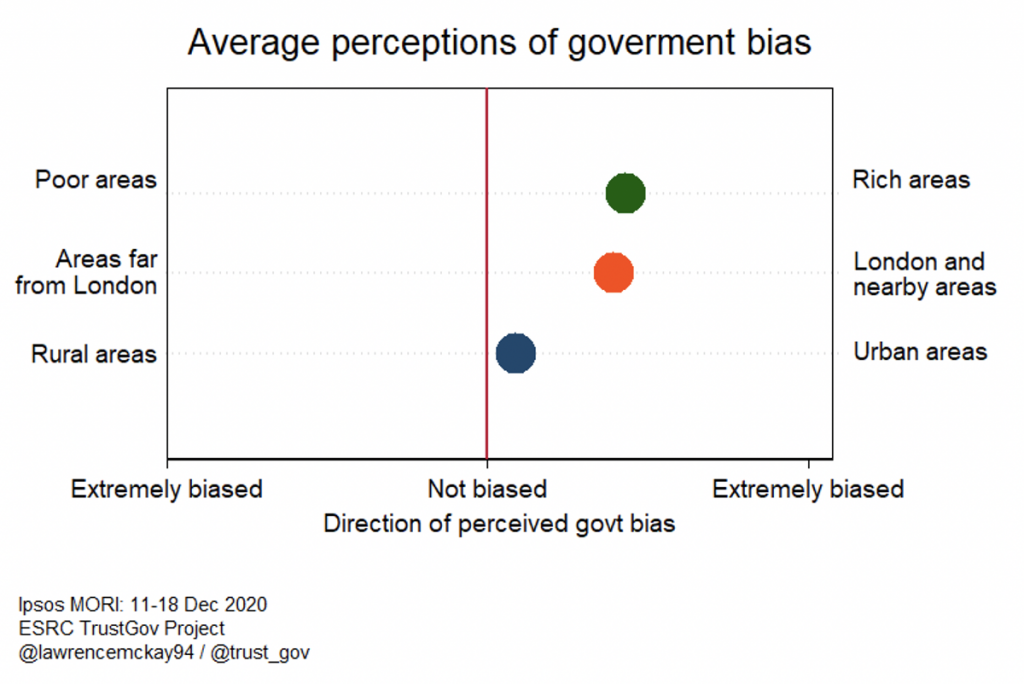

Few people think of their own areas as the winners in this arrangement: just 11% agree with the opposite statement, ‘the government cares more about people in my area than people in other parts of the country’. Which areas, then, do the British public think are actually favoured by government? Our next set of questions was designed to reveal this. We asked people to state on a scale whether government was biased ‘in favour of’ or ‘against’ particular types of places: urban and rural, poor and rich, and ‘far from London’ vs ‘London and nearby areas’. The graph below takes the difference in perceived bias for each pair of areas: the further from the red line, the greater the perceived bias towards one type of area over the others.

Urban-rural divides are rarely considered a key ‘cleavage’ in this highly urbanised country, and people indeed had a less strong sense of government being biased attitude – although the small rural minority did feel this more strongly. The other results are much more striking. Despite their increasingly working-class voter base, there is still a strong sense of class politics attached to the current government, which is seen by 69% of voters to be biased towards rich over poor areas. Furthermore, and perhaps most damning given the ‘levelling-up’ agenda, the government is overwhelmingly perceived to be biased towards London (roughly 70% endorse this view) and against areas far from the capital. This sense of bias is widely shared: people who see their own areas as richer than average hold the concern over favouritism to the rich, while Southerners and Londoners share the ‘London-centric’ criticisms made by Northerners (although not quite as strongly).

These results also go some way to explaining the North-South divide as to how much government is seen as caring about one’s area. Not only are Northern areas some distance from London, the perceived epicentre of political attention, but they are also more likely to be (and perceived to be) poor: 50% of Northerners thought they lived in a ‘poorer than average’ area, as opposed to around one in five Londoners and Southerners. As a result, the people who, in theory, stand to gain most from ‘levelling-up’ – Northerners who see their area as ‘poorer than average’ – most bitterly believe that the government cares less about them, by 78 to 10.

In conclusion, people in the North have a strong sense of feeling ‘forgotten’ in the early years of the Johnson government. As we do not have survey data about earlier governments using these questions, we cannot say whether this represents a worsening or just a lack of progress, but it certainly suggests a long, hard road to closing the trust gap. This is grounded in a strong sense of bias towards London and towards the rich, both of which reinforce each other to create ubiquitous and intense feelings of being forgotten in poorer parts of the North.

The government’s defenders might respond that it is too early to pronounce judgment on levelling-up: once people start to see tangible results, a real shift in perceptions will occur. However, a successful regional rebalancing is the work of decades, not years, even if policies are well-designed. Nonetheless, anyone who researches political trust will tell you that people care about process as well as outcome. How the government lays the groundwork for levelling-up, within this Parliamentary term, could therefore be make or break.

The emerging picture is of troubling signs for the project. The policy problem itself is ill-defined, sprawling and potentially undermined by contradictions. For example, the apparent intention to tackle inequalities both between regions and within them means that existing economic hubs within worse-off regions have no clarity about their role. The government has provided little indication of how it will involve local government in levelling-up, even though local leaders best understand the obstacles to success in their areas, and the conflicts between the central and local state have been worsened by Covid-19. The finance behind levelling-up may be constrained by a broader austerity agenda at Rishi Sunak’s Treasury. And the view of Whitehall economists on which projects are value-maximising might align little with how people in ‘left-behind places’ see their needs. For example, a recent survey suggests that people in deprived areas would give community facilities and meeting places a greater priority for ‘levelling-up’ than infrastructure projects.

Moving on from the pandemic and Brexit, the government plans to ‘make sure that 2021 is the year when levelling up becomes common political parlance’. Very likely, the foundations built this year will determine whether ‘levelling-up’ is a point of pride or a political punchline, and whether it holds out real hope of closing the trust gap.

____________________

Note: This research was produced as part of the TrustGov project, which is supported by the Economic and Social Research council (ES/S009809/1). The survey was also funded by the ESRC and was carried out by Ipsos MORI on behalf of the University of Southampton. Descriptive tables with results from all questions asked in this module of the survey are available here.

Ipsos MORI interviewed a sample of 1,476 adults aged 18+ in the United Kingdom using an online ad hoc methodology between 11th and 18th December 2020. Data has been weighted to the known offline population proportions for age, gender and working status, social grade and government office region within gender. All polls are subject to a wide range of potential sources of error.

Lawrence McKay (@lawrencemckay94) is a postdoctoral research fellow on the TrustGov project. His research concerns the relationship between geography, inequality and political trust.

Lawrence McKay (@lawrencemckay94) is a postdoctoral research fellow on the TrustGov project. His research concerns the relationship between geography, inequality and political trust.

1 Comments