Will austerity be repeated in the light of the ongoing pandemic? Sam Warner, Diane Coyle, Dave Richards and Martin Smith write that, while the evidence points to Rishi Sunak favouring belt tightening over exposing the public finances to further risk, this crisis underlines the need for fresh thinking within the Treasury, as well as for No.11 to engage more effectively beyond Whitehall.

The coronavirus pandemic has swept through the UK, leaving no community untouched. Even if the prospect of an early vaccine is realistic, it is clear that the economic impact will be with us for years to come. The human cost is sobering. Whatever questions might be asked about the government’s approach to crisis management, few would deny the monumental challenges associated with this public policy nightmare.

The Treasury has been at the heart of the government’s response. Its 11 March Budget Day cash injection of £30 billion – £12 billion of which was targeted directly at coronavirus – now seems like a drop in the ocean. By mid-March it was clear that the Chancellor would have to come back with a much larger second injection.

The scale and depth of the economic scarring is hugely contingent on the length of the lockdown. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research estimates that during the lockdown, GDP will drop by around 30% and by 7% for 2020. The damage limitation measures add around £75 billion to the deficit alone. In recent days, the Bank of England has suggested the hit to GDP in 2020 could be as high as 14%, the highest annual fall for 300 years. Over the next three months, the government’s borrowing will quadruple as the budget deficit is expected to reach just over 10% of GDP. Meanwhile, business activity has contracted at the fastest rate since records began.

The optimistic outlook of the Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) – a V-shaped recovery – has not dated well. The initial hit to public finances was necessary just to put the economy on life support. We must remember that ‘fiscal sticking plasters, no matter how big, need something to stick to’ and it is likely that the Treasury’s early interventions have secured that. Moving forward, re-opening the economy will require ‘hard choices’ and will inevitably be imperfect given the challenge of balancing so many competing demands. But, despite Boris Johnson’s ‘roadmap’ announcement, we remain some way off meeting the government’s five tests to significantly ease the lockdown. The economy will lurch forward again, although what the ‘new normal’ will look like is far from clear.

Paradoxically, despite enormous increases in public sector borrowing and debt, the fragility of the public finances will strengthen the Treasury’s hand in the power struggles ahead. Whatever Boris Johnson and Dominic Cummings might think, the reality is that the Treasury’s relationship with No 10 – like that of all spending departments – is interdependent and mutually constraining. But these are extraordinary times. At moments of acute crisis, the Treasury’s unique position at the heart of the core executive sets it apart in Whitehall. We need look no further than the Chancellorship of George Osborne to see the empowering possibilities a financial crisis can bring by reminding spending departments that the Treasury is boss. If opposition to Cummings’ No.10 influence was always likely, the Treasury might have reached the opportune moment. Whether the established model of central Treasury control and co-ordination is the right approach for UK governance in the longer term is a moot point and one our Nuffield project seeks to explore. But for now, No.11’s star is ascendant over the Whitehall village.

The Treasury has the reputation of being a hard fiscal taskmaster. Despite this deeply ingrained and collectively fostered austere mindset, it is malleable. Having previously encountered critical junctures, it has re-set itself on a different path. Invoking memories of wartime Britain is currently popular, but there is a serious point to be made regarding the Treasury. As the post-war landscape was (re)fashioned, the traditional Treasury View of the 1920s and ‘30s was shelved. While the wholehearted embrace of Keynesianism by Treasury officials might have been a slow burner, this period up until Thatcherism arguably signalled the zenith of Treasury responsibility and power. We could be forgiven for believing 2020 represents another juncture, one that will similarly lead to another era of No.11 dominance.

It must always be remembered that the Treasury is the most political department in Whitehall. Its tentacle-like influence means it is tuned into the challenges faced by spending departments. The label given by some that Rishi Sunak is Johnson’s ‘puppet’ Chancellor, may prove to be wide of the mark. The Chancellor will understand that appearing blind to political realities may well end badly. He is said to have an amenable style and his popularity has increased markedly. In Frances O’Grady, General Secretary of the TUC, he has found an unexpected advocate, praising his ‘real leadership’ and willingness to listen. His relative inexperience – the average cabinet experience of a UK finance minister is five years – has not yet proved a hindrance.

Those who know Sunak, including his former boss at the Treasury, Sajid Javid, suggest that the ‘coronavirus chancellor’ is not usually disposed to loose fiscal policy. Few would be surprised to hear George Osborne call for cuts to public expenditure once the initial phase of the crisis is over. Sunak, though, remains an unknown quantity. Reports that the Treasury is prepared to let some universities and airlines go under indicates the direction of travel. In line with the Treasury’s tendency to centralise, a dissenting senior official has lamented its ‘faith in their ability to carry out highly targeted just-in-time interventions…in the current circumstances’. Sunak’s reference to tax increases for the self-employed also carries the hallmark of Treasury officials. With similar predictability, the Chancellor’s decision to only guarantee loans up to £50,000 for small businesses might be further evidence that he favours belt tightening over exposing the public finances to further risk. Similarly, the Treasury is keen to ‘wean people off’ the job retention scheme due to concerns over its unsustainable costs.

Does this point to further austerity? The ‘wicked problems’ resulting from years of fiscal consolidation have never looked so stark and austerity fatigue was already an identifiable pressure on the Treasury. Boris Johnson has been quick to suggest his ‘instincts’ are against a return to austerity. Levelling-up has become his favoured political slogan, and if this was no easy task before, it is now a mammoth endeavour. It will be costly and, as we have recently argued, cannot be entirely driven from the centre. Numerous political, social, and economic constraints will have to feature in the Treasury’s thinking as it decides how deep its pockets will be.

First, the pandemic exacerbates existing inequalities as young people, women, BAME communities and the vulnerable – all over-represented among low earners – will be hit hardest by the economic fallout. There is an intergenerational dynamic emerging, as the young and low-paid find their prospects curtailed and their education adversely affected. The crisis has deeply impacted on the automotive and aerospace industries, with serious regional implications, especially for the North East and West Midlands. Given the political sensitivity of regional inequalities, this must feature prominently in Treasury thinking.

Second, at the local level, alarming reports of a growing funding gap of some magnitude have become commonplace as budgets have contracted during the austerity years. Cash strapped local authorities are creaking at the edges, with some reports suggesting a further £5 billion is required to avoid bankruptcy. The Communities Secretary has stated that councils cannot expect the exchequer to bear all of the costs associated with the coronavirus response. This will concern the Local Government Association Chairman, who informed the Local Government Select Committee that the £3.2 billion made available by the Treasury was light by ‘three or even four times’.

Third, is the greatest ‘wicked problem’ of all – social care. The Institute for Government notes that successive governments have left this costly policy conundrum unanswered. Given the alarming death rates in care homes, and the prospect of private care homes failing financially, further resolution cannot be delayed much longer. How would reform be paid for? No government wants to talk about tax reform as it is hardly an obvious vote winner, but there is an emerging consensus that increases must follow if policy imponderables are to be solved.

Fourth, the party political landscape is markedly different. Unlike 2010, the Labour Party will not support fiscal cuts, making Conservative Party statecraft more difficult. Anneliese Dodds, the new Shadow Chancellor, warned Sunak of ‘a generations-long crisis’ if the Treasury’s generosity is found wanting. Brexit, too, may soon become a further yoke around the government’s neck if the trough of the now likely U-shaped recovery stretches out.

This list is by no means exhaustive, but nonetheless points to factors that may sway the Treasury away from austerity Mark 2. Following the 2008 crisis, austerity was never the consensus among economists. This is more true today. The first part of the ‘new normal’, according to the OBR, is that public sector net debt will be permanently higher as a share of GDP. Whatever flimsy household debt analogies might suggest, the Treasury can go to the bond markets knowing that gilts remain a prized financial asset, while the interventions of the Bank of England ensure an overdraft is available to the Treasury at a low rate of interest. While estimates suggest that for each additional month in lockdown there will be £35 to £45 billion of additional borrowing, this figure will pale into insignificance if economic growth is not restarted.

Recently we wrote about the challenging fiscal landscape faced by the new Chancellor. Specifically, we drew attention to a paradox between the Treasury’s tendency for centralised control despite the increasing complexity and fragmentation of governance arrangements. We proposed – albeit tentatively – that a good deal of creative thinking would be required to meet the emerging challenges as the Treasury is forced to engage more effectively beyond Whitehall. The crisis underlines the need for fresh thinking. If, for example, the economic impact is differentiated spatially, what will be the role of the regions in resetting the economy?

The Treasury must act against the grain of its own history to avoid exacerbating the deep inequalities that this crisis has revealed. Moreover, it seems unlikely that public services can endure further budget cuts. The ‘porthole principle’ of Treasury control – that it is through the details that the bigger picture emerges – appears to have blinded the last austerity Chancellor to emerging ‘wicked problems’. A national conversation about how to pay for public expenditure is overdue. The Treasury is renowned for being home to the ‘brightest and best’ that Whitehall has to offer. Navigating the post-coronavirus landscape will certainly require their collective imagination but also an opening up of the thinking beyond Whitehall.

_____________________

Sam Warner, Researcher on Nuffield Foundation funded project Public Expenditure Planning and Control in Complex Times: A Study of Whitehall Departments’ Relationship to the Treasury (1993-Present), University of Manchester.

Sam Warner, Researcher on Nuffield Foundation funded project Public Expenditure Planning and Control in Complex Times: A Study of Whitehall Departments’ Relationship to the Treasury (1993-Present), University of Manchester.

Diane Coyle Inaugural Bennett Professor of Public Policy and co-director of the Bennett Institute for Public Policy.

Diane Coyle Inaugural Bennett Professor of Public Policy and co-director of the Bennett Institute for Public Policy.

Dave Richards is Professor of Public Policy and Head of Department at the University of Manchester.

Dave Richards is Professor of Public Policy and Head of Department at the University of Manchester.

Martin Smith is Anniversary Professor of Politics at the University of York.

Martin Smith is Anniversary Professor of Politics at the University of York.

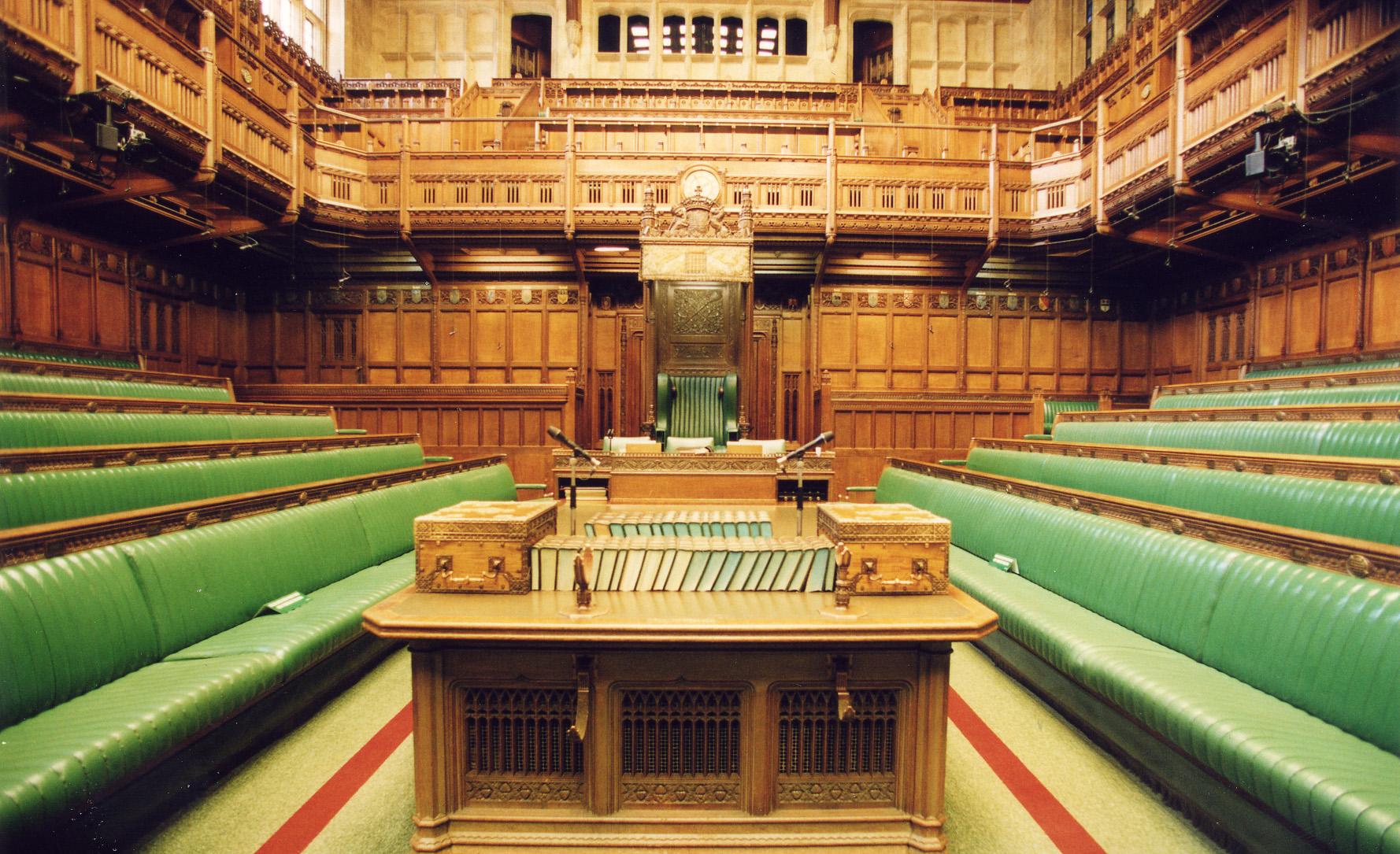

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

1 Comments