The recent upward revision of household debt forecasts illustrates one of the downsides of George Osborne’s plan to reduce the deficit. Nick Pearce writes that with low income growth predicted for the coming years, squeezed households may have little choice but to take on more debt.

The recent upward revision of household debt forecasts illustrates one of the downsides of George Osborne’s plan to reduce the deficit. Nick Pearce writes that with low income growth predicted for the coming years, squeezed households may have little choice but to take on more debt.

As the Observer reported last weekend, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has revised its household debt assumptions upwards. Last June, the OBR forecast that household debt would increase from an average of £58,000 for every household in the UK in 2010 to £66,000 by 2015. Now it expects it to rise to £77,000.

This is the downside of the Chancellor’s deficit reduction plan. As tax increases and public spending cuts squeeze households’ disposable incomes, they will be forced to take on more debt in an attempt to maintain their living standards. George Osborne talks of rebalancing the economy away from debt-fuelled government and household spending, and towards exports and investment, but the OBR’s figures show that his austerity programme will force households to take on more debt just to make ends meet. The future growth in the economy that is needed to bring unemployment down will only come about if we choose to live beyond our means.

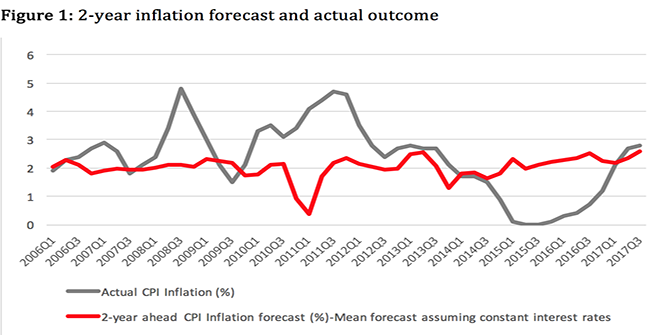

Real personal disposable incomes are forecast to increase on average by only 1.3% over the next four years (-0.4% in 2011, then 1.4%, 1.6%, 1.9% and 2.1% in the next four years). If the OBR was not forecasting an increase in borrowing and debt, then its forecasts for growth in consumer spending and GDP would have to be lower. Another way of looking at the OBR’s new forecast is that it has had to assume more household debt to avoid a cut in its medium-term growth forecast.

UK household debt is already the highest among G7 countries, which reflects the build-up of household debt in the long boom from the early 1990s onwards. (Although it is worth noting that the UK savings ratio peaked at the end of the post-war Keynesian period, and has declined since then, despite temporary rises during recessions, which suggests that household debt increases are also related to rising income inequality and the decline in the proportion of GDP going to wages, rather than profits.)

Another important issue to note is that 78% of debt (£1192 billion of £1531 billion in 2009) is secured on dwellings – ie mortgage debt – so reform of the housing market is needed before UK can tackle its debt culture. It is vital that housing supply is increased if we are to bear down on prices. The OBR does not break down its forecast but, barring an implausible explosion of unsecured lending, it must be assuming a revival in the housing market and mortgage lending, despite the fact that house prices are still high relative to incomes.

The OBR does present a saving rate forecast, which is the flow concept that drives developments in the stock of debt. It sees the saving rate dropping from 5.4% at the end of 2010 to 3.4% and then staying at this level – this would be low by long-run historical standards, if not by those of the second half of the 2000s. This highlights how the risk to the OBR’s growth forecasts are skewed to the downside: it is relying on historically low saving, to allow consumer spending to increase at a half-decent pace, and on an unusually strong performance from net exports.

There is also a strong political angle to all of this. In opposition, the Conservatives very successfully attached their critique of government borrowing to a wider public unease about personal borrowing and the consumer-spawned debt culture (its attack line, that the Labour government had ‘maxed out the country’s credit card’, perfectly draws this symbolic link). Voters were ready to believe that public and personal debt were two sides of the same coin of overspending and unsustainable consumption.

To a degree, of course, they were right: the health of the government’s finances was in part dependent on economic growth that derived from personal borrowing, rather than savings and exports. But as Keynes long ago pointed out, nations are not households: government borrowing is the only way to support growth during a recession, and central banks are the backstop for reflating battered economies – it works in ways that are meaningless at a household level.

More importantly, however, if household debt is set to rise in the coming years, voters may be less inclined to allow their personal circumstances to be rolled up into a wider critique of government borrowing under Labour. The symbolic link between the two may be sundered, and the word ‘debt’ starts to take on new political meanings.

This article first appeared on the IPPR’s site on 5 April.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.