Ian Simpson explores how public opinion is changing in ‘Conservative gain’ and ‘Conservative hold’ seats in England and Wales. He writes that such an analysis reinforces the point that under our electoral system, not all voters are equal.

Ian Simpson explores how public opinion is changing in ‘Conservative gain’ and ‘Conservative hold’ seats in England and Wales. He writes that such an analysis reinforces the point that under our electoral system, not all voters are equal.

We often hear about the knife edge nature of elections due to the warping effect of First-Past-The-Post (FPTP). Since the 2017 election we’ve often heard that Labour were just 2,227 votes away from an overall majority in a handful of seats. Equally, that same result is often flipped to note that the Conservatives, were just 93 votes short of a majority. However, such arguments often miss the key point about FPTP: it is not overall changes in votes that matter, but the type of seats where those changes take place.

For example, at the 2019 general election, the Liberal Democrats increased their vote share by four percentage points but suffered a net loss of seats. Meanwhile, the Conservatives made a net gain of 47 seats, despite only increasing their vote share by one percentage point. This was because they tended to lose votes in relatively ‘safe’ seats where they could afford to take a hit, while seeing above average increases in seats they targeted as potential gains.

This pattern of divergent changes in vote shares in different types of seats is increasingly prevalent in British politics, with the days of uniform swings across the country long gone. The most striking example is Scotland, where the party system now looks very different to the rest of Britain. According to recent Scottish-specific polls, the SNP continues to dominate, recording support of 50% or more. For clues about the Conservative versus Labour battle, we must look to England and Wales.

Opinium polling

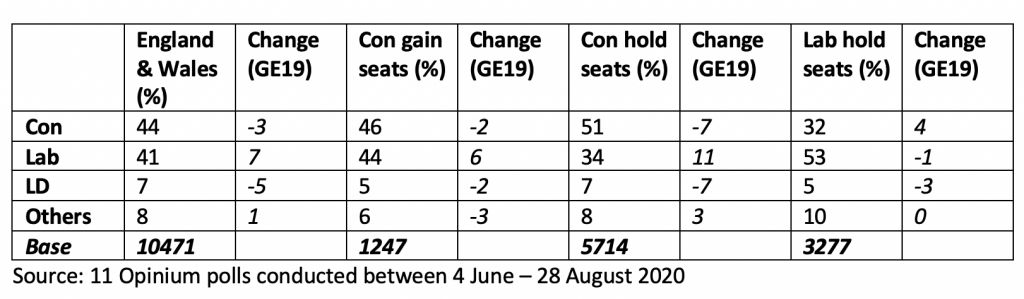

Since June, Opinium have made a useful addition to their opinion poll data. They have started to break down their results for England and Wales by type of seat at the 2019 general election – ‘Conservative hold’; ‘Labour hold’; ‘Conservative gain’ – categories which cover all but 13 seats in England and Wales. This allows us to explore how public opinion might be changing across different types of seat.

There has been much focus on ‘Red Wall’ seats – the 50 seats the Conservatives gained from Labour across Wales, the Midlands and the North of England. These are widely regarded as crucial to Labour’s prospects of returning to government. These 50 seats form the vast bulk of the ‘Conservative gain’ category.

One poll would not be enough to reliably assess public opinion in these seats, as in any one poll there are usually just over 100 respondents from ‘Conservative gain’ seats. However, adding a number of polls together allows us to get a reasonably accurate view of what might be occurring. From the start of June to the end of August, Opinium conducted 11 polls, with a combined 1,247 respondents from ‘Conservative gain’ seats, around the same number as a standard opinion poll. The consistency of the findings across these polls is another factor that justifies combining them. Nine of the 11 polls showed a Tory lead across England and Wales of between one and four percentage points. One showed a Tory lead of eight points and the other, the most recent, a Labour lead of one point.

Table 1: Party vote shares across England and Wales based on Opinium polls.

Red shift?

The data indicates that Labour is making some progress in the seats it lost to the Conservatives in 2019, seeing their vote up six points in the ‘Conservative gain’ seats, compared with the general election. However, it must be noted that Conservative support there appears to be holding up relatively strongly, being down only two points.

If Labour were to achieve the 4% swing indicated in this polling, they could expect to win back around 32 of the 54 seats they lost to the Conservatives last year. Assuming no other changes elsewhere, the swing in the ‘Conservative gain’ seats would still leave Labour on what by historical standards would be a very low 235 seats. This does not take into account the possibility of Labour losing more of the seats it held onto last year, which should not be discounted given the indication of a small swing to the Tories in Labour-held seats.

If Labour were to achieve the same 4% swing in ‘Conservative hold’ seats, it would net them only about 10 further gains from the Tories, leaving them still well short of being the largest party and with a likely Conservative majority. Labour, however, appears to be making far greater advances in these Conservative hold seats than the ones they lost in 2019, with a swing of 9%. Such a swing could see Labour win about 42 of these seats, which would likely see the Conservatives and Labour on about the same number of MPs and put Keir Starmer in a strong position to become Prime Minister, given the unlikely prospect of the other parties in parliament supporting the continuation of a Conservative-led government.

Perhaps Labour’s greater progress in these seats is not surprising, considering that polling indicates that Starmer is proving attractive to GE19 Lib Dem voters. This is an important factor in these seats, as there were double the number of Lib Dem voters (15%) in ‘Conservative hold’ seats than in other seats at the general election. A note of caution is required here though – of these 42 seats Labour could expect to win on a 9% swing, only nine had a Lib Dem vote share higher than 10% in 2019. However, the relatively large Tory fall in these seats (seven percentage points) would appear to give genuine hope to Labour and possibly the Liberal Democrats if they can continue to position themselves as the clear challenger to the Conservatives in particular seats.

Failing voters

While interesting, this analysis reinforces the point that under our FPTP electoral system, not all voters are equal – and that changes in support for different parties are not necessarily reflected in representation in parliament. A democracy where the outcome of an election is based more on where voters change their support than how many do so cannot properly claim to represent the people it serves.

Genuine shifts in public opinion being properly reflected in our elected chambers should be a cornerstone of our democracy. A change to a system of Proportional Representation would provide certainty to both parties and more importantly to voters: that their vote matters, wherever it is cast.

_________________

Ian Simpson is Research Officer at the Electoral Reform Society.

Ian Simpson is Research Officer at the Electoral Reform Society.

Photo by Wesley Tingey on Unsplash.

Anthony Tuffin, In percentage GAIN terms you are correct but only in that sense. However, what the experience of the Lib Dems at the last election serves to demonstrate is just how fundamentally irrational and stupid FPTP is. A sane electoral system SHOULD provide a CLEAR LINK between a party’s popularity or not with the electorate and its seat share in the House of Commons ie if it LOSES real support it SHOULD LOSE seats as well and it is becomes MORE POPULAR as the Liberal Democrats did from 2017 to 2019 it SHOULD GAIN MPs. It is high tine time this irrational lottery of FPTP was ended for good.

I would like to replace it with the German system of Mixed-Member Proportional Representation but instead of having ‘closed’ regional PR lists as they do have ‘open’ ones instead so that voters can choose to endorse individual candidates from within the regional party lists.

Increasing your vote share from 7% to 11% is an increase of four percentage points just as the article suggests.

I am not a member of the Lib Dems but, their vote share increased from about 7% in 2017 to about 11% in 2019. Simple arithmetic shows that that is an increase of 57%, not 4%, and yet they lost a seat.