Falling poverty rates could indicate gentrification, or they could mean that London is now a more fair, socially mixed and cohesive city. Alex Fenton looks at what happened to poor neighbourhoods under New Labour in the 2000s, and argues that shifting rates in poverty fail to tell the whole story.

Falling poverty rates could indicate gentrification, or they could mean that London is now a more fair, socially mixed and cohesive city. Alex Fenton looks at what happened to poor neighbourhoods under New Labour in the 2000s, and argues that shifting rates in poverty fail to tell the whole story.

There has been much speculation as to whether the coalition’s housing policy, especially on Housing Benefit, will displace lower-income households from inner London. At the same time, some worry that income inequality means that rich and poor households live increasingly segregated from one another into well-off and disadvantaged neighbourhoods. The Centre for Analysis for Social Exclusion has been looking at what happened to poor neighbourhoods under New Labour in the 2000s as part of a major research project for the Trust for London. We find that in London poverty was already becoming more suburban and more diffuse even as income inequality in the city rose.

Income poverty is not directly measured at neighbourhood level, so we use the rate of receipt of means-tested benefits among working-age adults as a proxy. Although these rates are lower than conventional definitions of income poverty (around 28% of all London households during the 2000s), it gives a picture of its relative spatial distribution. The first map shows neighbourhood poverty estimates in 2001 and 2010.

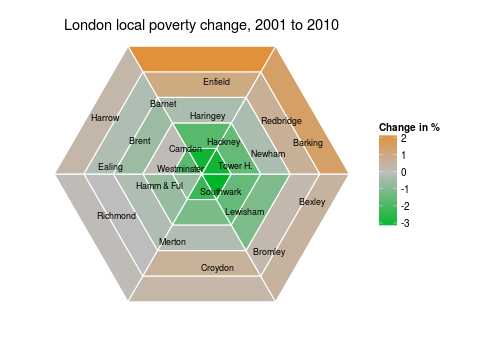

The same broad pattern of higher poverty in the east persisted, but there are now many fewer neighbourhoods with exceptionally high rates in inner London. The trends can be brought out by mapping the change for larger sectors arranged by distance from the city centre. Poverty rates fell fastest in central London, and, in detail, fell the most in those neighbourhoods which were the most deprived in 2001. At the same time, poverty rates rose in much of Outer London, especially in the eastern suburbs. By several measures of difference or polarisation, the income-poor became less segregated; the poorest neighbourhoods became steadily less extreme relative to the city average.

The trends can be brought out by mapping the change for larger sectors arranged by distance from the city centre. Poverty rates fell fastest in central London, and, in detail, fell the most in those neighbourhoods which were the most deprived in 2001. At the same time, poverty rates rose in much of Outer London, especially in the eastern suburbs. By several measures of difference or polarisation, the income-poor became less segregated; the poorest neighbourhoods became steadily less extreme relative to the city average. We know that income inequality, as measured for example, by wages, rose in London. The gap between the highest incomes and the rest is growing the fastest. In light of this, the suburbanisation and diffusion of poverty might thus seem a surprising finding. How might it be explained, and does it matter anyway?

We know that income inequality, as measured for example, by wages, rose in London. The gap between the highest incomes and the rest is growing the fastest. In light of this, the suburbanisation and diffusion of poverty might thus seem a surprising finding. How might it be explained, and does it matter anyway?

One part of the story is the privatisation of housing welfare during the 2000s. At the beginning of the decade, around 90% of households in subsidised housing were rented directly from a council or housing association. Over the 2000s, there was a net loss of around 25,000 social housing units, almost all in Inner London. The largest part of these losses were due to the Right-to-Buy; several thousand dwellings were also demolished. These losses, and the additional housing need arising from a growing population and static poverty rates were met by publicly subsidised renting from private landlords. The number of Housing Benefit claimants in private rented housing rose from 100,000 in 2002 to 250,000 in 2010. The numbers rose fastest in Outer London, where market rents are lower.

Thus, there are now fewer low-income households renting in the inner city on council estates, and more living in private rented housing in a wider range of neighbourhoods. We might read this as the state-sanctioned break-up of urban working-class communities. Or we could see the introduction of market-based choice in housing as enabling subsidised poor households to make the same moves that households with means have long made in London. There are long-established patterns of outward migration made by families with young children; the privatisation of housing welfare enabled some poor households to follow a similar path.

We should also look more closely at what accounts for falling poverty rates. Dwelling and population density increased substantially in inner London over the period, and did so most in the poorest neighbourhoods. Importantly, the number of people of poverty there fell only slightly, but the total number of working-age adults rose greatly – by about 20% in the poorest inner-city areas. Working-age, employed adults moved into in newly constructed flats, such as those to be seen on watersides in Hackney, Tower Hamlets and Islington. Changing poverty rates don’t tell the whole story – or at least, we have to ask whether it was the top half of the fraction (the number in poverty) or the bottom half (the total resident population) that changed. Falling poverty rates don’t necessarily imply fewer people in poverty.

Looking at rates and counts over time doesn’t tell us whether these changes matter or not. Talking about the material and social differences between places (for example, differences in life expectancy) within a country or city is often simply a way of pointing out inequality in general in British society, rather than saying something specific about those places.

Our research will be looking further at some specific questions about poor neighbourhoods as places both under New Labour and under the coalition. For example, are these trends a good thing because they mean that fewer people are subject to the most difficult neighbourhood conditions associated with concentrated poverty, such as crime, inferior services and a dilapidated public realm?

There are other questions whose answers reflect views of a good city and a good society; they are matters of value rather than fact. So, for example: are these changes bad because they indicate gentrification, or do they mean that London is now more fair, socially mixed and cohesive city? It is worth being suspicious of accounts of ‘cohesion’, ‘deviance’ or ‘integration’ that look only at poor neighbourhoods as the location of social problems, and hence the proper object of intervention.

Finally, are we merely at a transition point between the London of the 1970s and 1980s, with its falling population, disinvestment and the departure of the middle class, and a London of the future, with inner neighbourhoods populated by wealthy consumers and the poor priced out to parts of the periphery? Given how central housing is to the mayoral debates, our findings prompt important questions about the kind of city Londoners want to see, and how it can be fashioned.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

About the author

Alex Fenton is a Research Fellow in the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion at LSE. From 2006 to 2011 he worked at the Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research, in the Department of Land Economy at the University of Cambridge.

4 Comments