Does physical appearance really matter when it comes to doing well in work? Is it true that pretty people do better in life? A new study by Emanuela Sala, Marco Terraneo, Mario Lucchini and Gundi Knies suggests the attractiveness factor can indeed have an effect on the shape of our working lives. Prettier people do get more prestigious careers than their plainer peers.

Does physical appearance really matter when it comes to doing well in work? Is it true that pretty people do better in life? A new study by Emanuela Sala, Marco Terraneo, Mario Lucchini and Gundi Knies suggests the attractiveness factor can indeed have an effect on the shape of our working lives. Prettier people do get more prestigious careers than their plainer peers.

Most studies of inequality tend to focus on how we all have different types of ‘capital’ that help us to get on in life. For instance academics have looked at how ‘cultural capital – education – or ‘social capital’ – personal ties – can play a role. But other types of social resources can be important, too. Catherine Hakim, for example, argues that ‘erotic capital’ may be an additional asset that influences people’s life chances. Although there is not very much research in this field, a number of studies have shown that people’s physical appearance does matter.

Indeed, physical appearance is associated with a wide range of socio-economic outcomes including happiness, family formation and break-up, electoral success and career opportunities. Research has shown, for example, that tall, slim people earn more than short, obese people.

Our recent paper investigates the effects of men and women’s physical attractiveness over the course of their employment history. Our research offers a fresh perspective to the study of social inequalities and could improve the current understanding of whether physical attractiveness affects people’s employment careers. We explored the impact of beauty over people’s life course by tracking 4,200 participants in the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study over 35 years. A panel of experts assessed the participants’ high school yearbook photos and awarded each a beauty score.

Those with the highest beauty scores were found to have the better jobs and more prestigious careers over those with lower scores, despite other differences in socio-economic background, parent education and even their own IQs. In particular, we found that even after controlling for other variables such as when the respondents were born, their level of education and their parents’ social status, people with more attractive faces tended to start out in higher-status jobs.

The effect, it seems, remains constant throughout men’s and women’s career histories – there was no significant difference in the impact of beauty as they aged and progressed in their careers. In other words, facial attractiveness is as important in determining people’s occupational prestige at the beginning of their careers as it is in the middle or at the end. (Occupational prestige is measured by an index, the socio-economic index (SEI), developed by Featherman, Sobel and Dickens in 1975.)

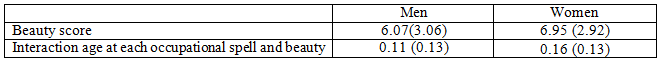

The effect seemed to be somewhat larger for women than it was for men – a single ‘unit’ increase in a woman’s attractiveness increased her occupational score by 6.95 points, whereas the comparable occupational boost for a man was 6.07 points. This means, for instance, that a woman that is “attractive” rather than “very attractive” suffers a loss in occupational prestige that is approximately that of being a Political Science teacher rather than a Chemistry teacher, or, to give an example further down the occupational prestige scale, being a Cashier rather than a Computer Operator. For men, a change in occupational prestige of 6.05 would be approximately equivalent to moving from the occupational prestige of a Cost and Rate Clerk to the prestige of a Manager of Food Serving and Lodging Establishments.

Table 1: Main findings of multilevel Conditional Growth Model. Coefficients and standard errors (in parenthesis)

Source: Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS)

Note: A single ‘unit’ increase in a woman’s attractiveness increased her occupational score by 6.95 points, whereas the comparable occupational boost for a man was 6.07 points

Controls include year of birth, age of entry in the labor market, intelligence quotient, number of years of regular schooling, father’s years of schooling, father’s socio-economic index, number of siblings, mother’s years of schooling.

The findings raise a number of questions regarding the processes that underlie the reproduction of social inequalities. For example, do beautiful men and women have higher occupational prestige because employers discriminate against plain people? Or is it that beautiful men and women choose more prestigious occupations, for example, because they enjoy a higher self-esteem and are more self-confident?

Our current knowledge on the impact of these types of ‘non-conventional’ capital on major social outcomes is quite limited. However, this would certainly prove a promising field for further study, if information on different aspects of respondents’ physical attractiveness were to be collected more systematically in future studies.

Collecting this information on a longitudinal basis would be particularly valuable. The Wisconsin Longitudinal Study does, for instance, not allow us to look at how people have changed their looks over time – in fact, we had to assume that people’s physical attractiveness remains constant over time. But lifestyle choices such as smoking or poor diet, and environmental factors such as pollution are known to impact how we change our appearance. And last, but not least, we also know that people invest a lot of money on changing their relative position in the league of the beautiful: Americans and people living there spent $11 billion last year on various purely aesthetic – and technically unnecessary – cosmetic procedures.

We can only concur with Catherine Hakim when she says there are difficulties in measuring beauty; but this should not be an excuse for failing to properly evaluate its influence on major aspects of our lives.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Authors

Gundi Knies is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Social & Economic Research at the University of Essex. She is a quantitative researcher with training and research experience in economics, social policy and sociology. Her research focuses on longitudinal analyses of income distributions and poverty, life satisfaction and neighbourhood effects using a range of datasets, including the German Socio-economic Panel (SOEP), the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) and Understanding Society. Gundi is a member of the design and implementation team of Understanding Society and is on Twitter as @GundiKnies.

Gundi Knies is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Social & Economic Research at the University of Essex. She is a quantitative researcher with training and research experience in economics, social policy and sociology. Her research focuses on longitudinal analyses of income distributions and poverty, life satisfaction and neighbourhood effects using a range of datasets, including the German Socio-economic Panel (SOEP), the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) and Understanding Society. Gundi is a member of the design and implementation team of Understanding Society and is on Twitter as @GundiKnies.

Emanuela Sala is a lecturer at the Department of Sociology and Social Research at the University of Milano Bicocca and a research associate of the Institute for Social and Economic Research at Essex University. Since 2006 Emanuela is one of the vice-presidents of the Research Committee Logic and methodology of the International Sociological Association.

Emanuela Sala is a lecturer at the Department of Sociology and Social Research at the University of Milano Bicocca and a research associate of the Institute for Social and Economic Research at Essex University. Since 2006 Emanuela is one of the vice-presidents of the Research Committee Logic and methodology of the International Sociological Association.