Issues with public procurement during the pandemic have brought to the fore the importance of transparency. Calls for greater transparency in the negotiation, award, and renegotiation of public contracts are not new, but how much progress has been made in recent years, and how has the COVID-19 influenced approaches to public contracting? Stéphane Saussier shares some initial findings from research looking into these questions.

Issues with public procurement during the pandemic have brought to the fore the importance of transparency. Calls for greater transparency in the negotiation, award, and renegotiation of public contracts are not new, but how much progress has been made in recent years, and how has the COVID-19 influenced approaches to public contracting? Stéphane Saussier shares some initial findings from research looking into these questions.

In April 2015, Jean Tirole and I examined ways to strengthen the efficiency of public procurement. It seemed to us that the great leeway left to contracting parties to renegotiate their contracts and deal with unforeseen events should be accompanied by increased transparency. This, in turn, would help to ensure better control of public procurement spending in EU, estimated at 14% of the EU GDP.

The EU directives that have applied in Europe since 2016 (2014/23/EU, 2014/24/EU, 2014/25/EU) are a step towards more transparency. By establishing an obligation to publish information on changes to public contracts during their execution, these directives allow access to new data. As a result, they pave the way for new research, in particular on the influence of COVID-19 on the execution of public contracts.

Recently, the Sorbonne Business School and Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford launched a study to examine contract renegotiations in Europe in the context of COVID-19. We looked at all the contract modification notices listed in the Tenders electronic daily (TED) database, built by the Official Journal of the European Union. The preliminary results are presented here. We are also surveying all 27 EU member states and UK public authorities to understand more in details how they perceive contract renegotiations.

Regular skidding

For many years, economic analysis has emphasised the incompleteness of these contracts. As these contracts are incomplete, they often have to be adapted during their execution. Different reasons can be invoked during renegotiations: ill-conceived contracts, unforeseen events, opportunistic behaviour, corruption, or even winner’s curse issues (i.e., the winning bid is overly optimistic, and the party will have to renegotiate later on). They often entail significant additional costs for the public sector.

A few examples of impressive ‘slippages’ appear regularly in the press. Among the textbook cases, we find that of payment by results outsourcing of probation services in England that was ultimately terminated early. From NAO report: £467 million additional projected payments to CRCs [providers] above the original terms of the contracts between 2016-17 and December 2020.

Such slippages are so frequent that we have gotten to the point where no one takes the initial estimate of major projects seriously anymore – renegotiation is the rule, not the exception, and this might lead to a significant increase in procurement costs.

Significant differences between European countries

The European directives approved in 2014 and applied since 2016 were for the first time concerned with the execution phase of contracts and no longer just with their award. While modification of contracts is allowed, to a large extent, the directives oblige public contractors to publish information on developments decided by the parties.

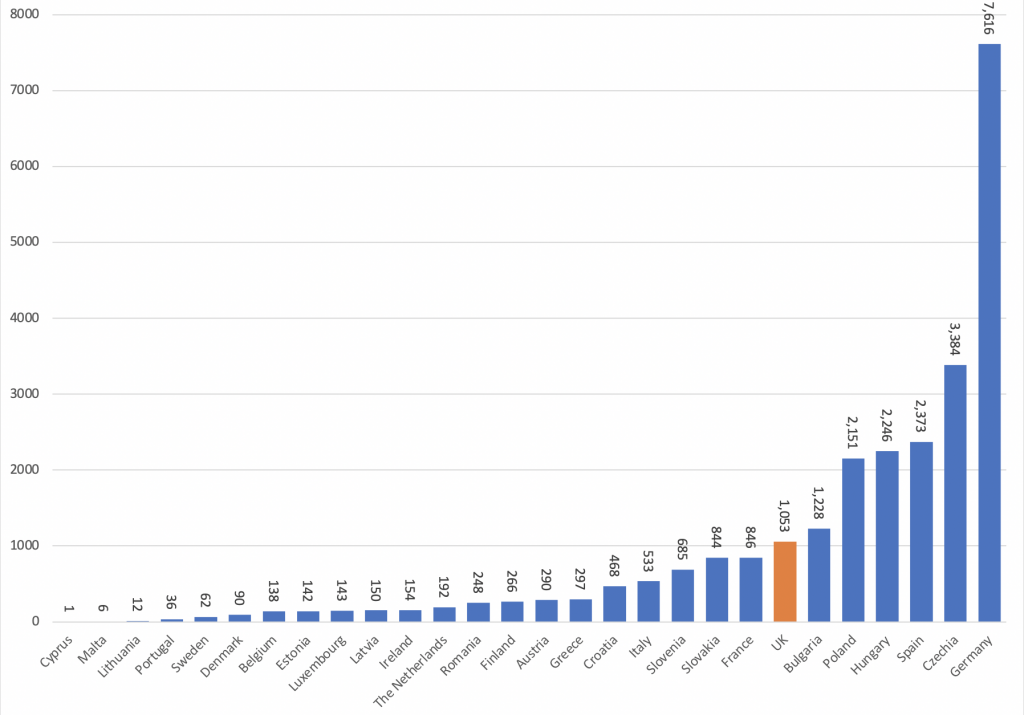

Figure 1 shows the modifications of public contracts listed in the TED database. It points to significant differences between EU countries, and suggests that some are immune to contract renegotiations. However, it seems more likely that these countries do not effectively transmit information on renegotiations to the database.

Figure 1: Number of contract modifications per EU country (January 2016-May 2021).

Still, significant differences also appear between countries that seem to transmit information well – for example, between UK and Germany. These discrepancies can be explained by the number of contracts concluded, by an over-transposition of European directives in certain countries (with national rules which would, for example, require the publication of information on all contractual renegotiations, even those not having no financial impact on contracts), by cyclical characteristics specific to certain countries, or by different traditions of drafting and renegotiating contracts.

A destabilising effect of COVID-19?

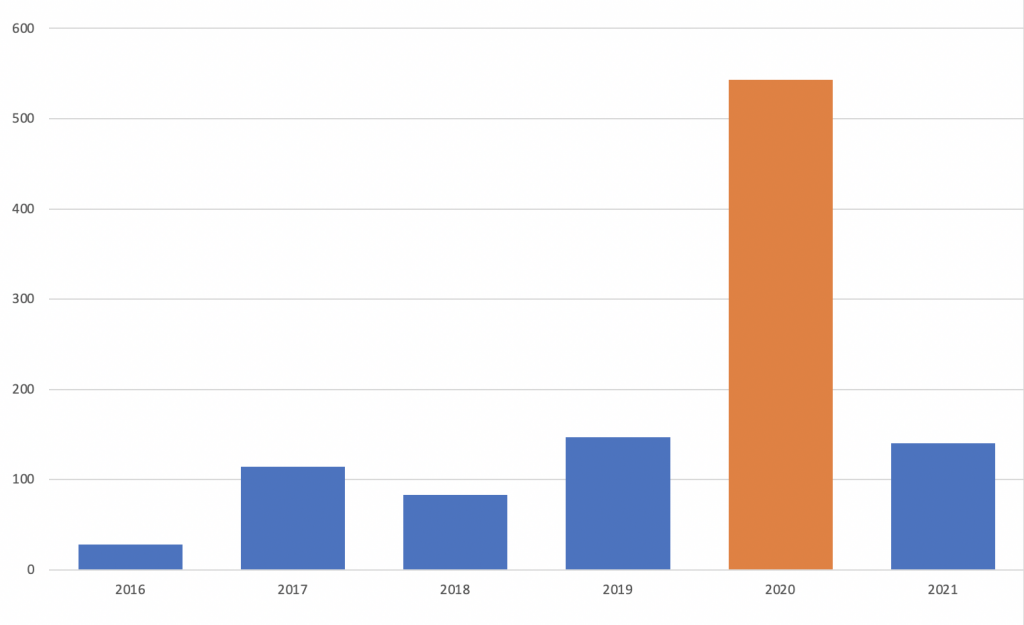

Although imperfect, these data make it possible to carry out initial analyses of contract modifications and their financial consequences in the UK, a country for which the database appears to be well informed. Since 2016, modifications of public contracts seem to be more and more numerous. The low number of renegotiations recorded in 2016 and 2017 is, however, probably explained by a reporting system that is still imperfect.

Figure 2: Number of renegotiated UK contracts per year (January 2016 – May 2021).

It is important to note that the vast majority of contract changes resulted in increases in public spending. For the most part, they remain contained at increases of less than 20% of the amount of the contracts. However, some lead to substantial increases in the contract amounts, of more than 50%.

Figure 3: UK contract amount changes after renegotiations (January 2016 – May 2021).

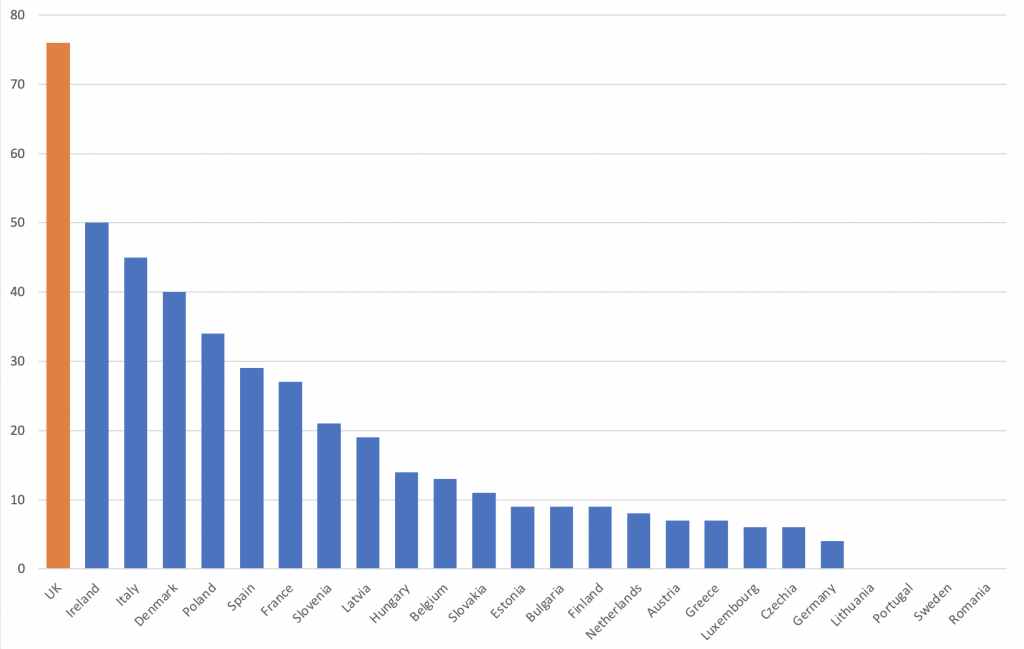

TED data also provides a more detailed understanding of the reasons for renegotiations. Indeed, the public authority must provide a justification, in a few lines, for each modification. A textual analysis thus makes it possible to highlight the destabilising effect of the COVID-19 crisis. In the UK, more than 70% of contracts renegotiated since December 2019 have been due to the health crisis. That is very specific to the UK. Conversely, this percentage remains very low in Germany.

Figure 4: % of renegotiated contracts for COVID-19 reasons (since December 2019).

Once again, these differences between countries raise questions. While this may be the result of methodological errors, one can also wonder about the characteristics of contracts, the nature of contractual relationships, and the status of renegotiations in these different countries.

Upcoming research

This first step towards more transparency is commendable. However, TED data does not provide a clear view of the conflicting or cooperative nature of contract changes. This issue is essential. Do changes to contracts, even expensive ones, reflect a positive contractual relationship and the willingness of the players to move towards more efficiency by adapting the contract to new situations? Or do they result from a lack of preparation of the contract or the opportunistic behaviour of the actors?

To shed more light on the nature of contract changes, the Sorbonne Business School and the Blavatnik School of Government have launched a questionnaire survey to public buyers in Europe. We believe that the response to COVID-19 can act as an indicator of the quality of the contractual relationship between the parties. This type of exogenous shock also prompts us to question the more or less rigid nature of contracts, which can influence their ability to adapt to unforeseen contingencies at the time of their signature.

We will address these questions, and our work will aim to supplement these initial statistics with finer data. They will provide a better understanding of the characteristics of contractual renegotiations, an essential facet of public procurement.

_____________________

Stéphane Saussier is Professor of Economic and Public Management at the Sorbonne Business School-University Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne

Stéphane Saussier is Professor of Economic and Public Management at the Sorbonne Business School-University Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne