Erica Holt-White discusses applicants’ concerns about attending university in the autumn of 2020 as well as the potential of the grading process for negative impacts on disadvantaged groups. She nevertheless explains why, with concerted action and a willingness on the part of universities to be flexible, long-term damage may be averted.

Erica Holt-White discusses applicants’ concerns about attending university in the autumn of 2020 as well as the potential of the grading process for negative impacts on disadvantaged groups. She nevertheless explains why, with concerted action and a willingness on the part of universities to be flexible, long-term damage may be averted.

Results day 2020 has been a first, with thousands of students in England, Wales and Northern Ireland receiving A-level results based on teacher assessments and a statistical model, instead of receiving their grades following a set of exams. While we are starting to build the picture, the full effect of this new system and its impact on the prospects of young people across the country will not be known fully immediately. It will be vital to look in greater detail at the impact these changes have had in the near future, particularly looking at which groups have been most likely to lose out in the process. The Sutton Trust, along with Education Datalab, intend to do just that in the coming weeks. Nonetheless, from the latest polling by the Sutton Trust of university applicants, it is already clear that uncertainties and worries ahead of this year’s exam results, along with concerns about what university will look like this autumn, are both having a considerable impact on applicants.

University applicant attitudes

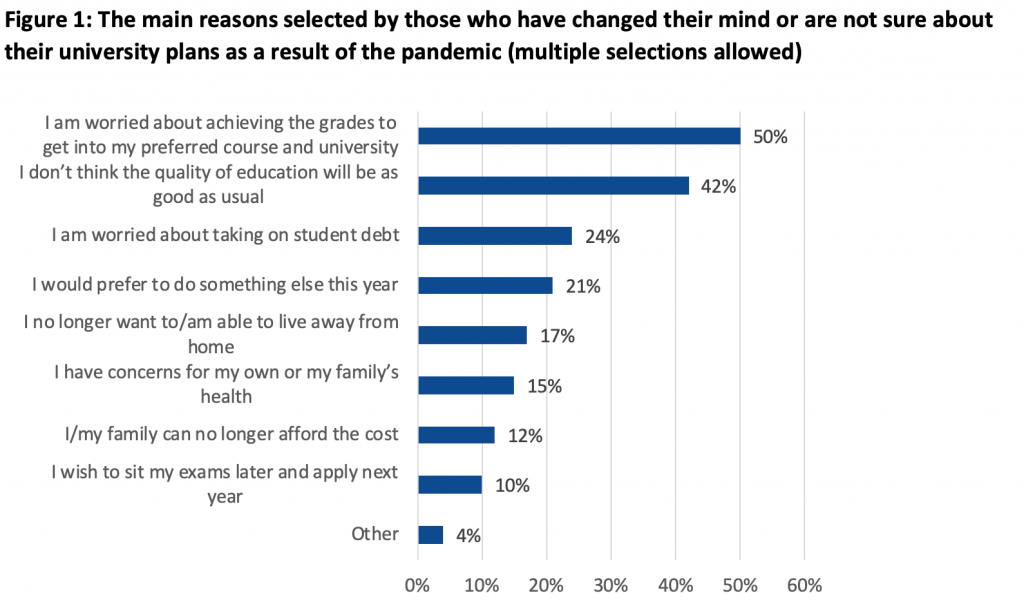

One in five students applying to university have changed their plans or are uncertain about attending university this autumn as a result of the pandemic. Of those still uncertain, half are worried about achieving the grades to get into their first-choice course, 42% worried the quality of education wouldn’t be as good as usual, and just under a quarter (24%) were worried about taking on student debt.

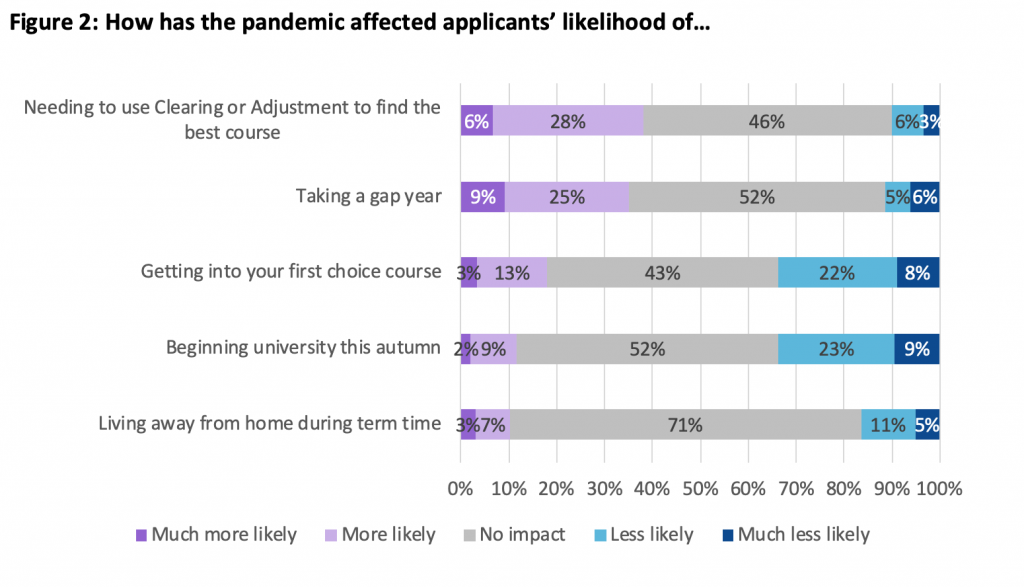

While only 5% of applicants have so far made the decision to defer, 32% said the pandemic has made it less likely they will begin university this autumn. Just over a third (34%) of applicants reported the pandemic had increased the likelihood they would need to use Clearing or Adjustment, whilst 34% also reported being more likely to take a gap year.

Our polling also uncovered concerns about attending university in an unprecedented year; social activities at least in the first semester are unlikely, with a blended model of face-to-face and online teaching expected for the foreseeable future. We found that three quarters (73%) of applicants are worried about how the pandemic will impact their ability to take part in university social life over the next 12 months, and two thirds are worried about the impact of little or no face-to-face teaching. Just over half (54%) are worried about the possibility of catching or spreading COVID-19.

Many observers warned at the outset of the decision to award grades on the basis of ‘moderated assessment’ of the potential for negative impacts on disadvantaged groups. However, the strength of feeling generated with the release of Scotland’s SQA results at the beginning of August surprised many. What those figures revealed was that a system which is heavily reliant on a school’s previous performance risks baking in historical disadvantage. While educational inequalities are often too easily ignored, a grading system which deliberately replicates and reinforces that inequality has crossed the threshold of public acceptability. While every year students at the most disadvantaged schools will, on average, have lower performance than their peers, individual students and cohorts will buck this trend. Knowing which students would do so in the absence of actual exams is an almost impossible task, but by relying so heavily on a centre’s previous performance, without due consideration of the individual potential of strong students or of a cohort, the system serves to entrench disadvantage.

Ensuring students from poorer backgrounds do not suffer due to the system put in place to replace exams this year should remain paramount. The Sutton Trust, among others, have strongly urged Ofqual to closely monitor attainment gaps in the new grading system, and to consider how best to respond if substantial gaps open up. To ensure students can have confidence in this year’s system, it is also important that the appeals process is fair and accessible, with any fees waived so that there are no financial barriers to the process. This is especially important given the government’s recent announcement that mock exam results can be used as a part of these appeals. In theory, this could give a chance for high performing students at historically low performing schools to have their results corrected, but needs to be fully accessible to all if it is to improve fairness. There are also significant questions about the consistency and validity of mock results across schools, and it is vital that the appeals process puts such marks in the correct context.

However, while accessible appeals are important, given the short time frame available, quick action will also be needed by universities. The recent call by Universities Minister Michelle Donelan for universities to be flexible in their admissions this year is to be welcomed. The Sutton Trust has long advocated for institutions to make greater use of contextual admissions, basing offers both on a student’s grades and the context in which they were achieved. This year, universities should use the same principles to recognise that students’ grades have been awarded in the most extraordinary of circumstances, and give students the benefit of the doubt if they have just missed their offers, particularly those from less well-off backgrounds or attending more deprived schools.

Results day is a crucial time for so many pupils and parents across the country, particularly after months of uncertainty due to the pandemic. But despite the stress and confusion caused by this year’s grading process, with concerted action and a willingness to be flexible, long-term damage to young people’s futures should not be seen as inevitable.

_____________________

Erica Holt-White is Research and Policy Officer at the Sutton Trust.

Erica Holt-White is Research and Policy Officer at the Sutton Trust.

Photo by Akshay Chauhan on Unsplash