Public engagement remains one of the most tangible ways universities can demonstrate their impact. Fred Robinson finds that in a time of stretched resources, universities can play a much greater role in engaging with local disadvantaged communities, producing a wide-range of mutual benefits.

Public engagement remains one of the most tangible ways universities can demonstrate their impact. Fred Robinson finds that in a time of stretched resources, universities can play a much greater role in engaging with local disadvantaged communities, producing a wide-range of mutual benefits.

This article first appeared on the LSE’s Impact of Social Sciences blog

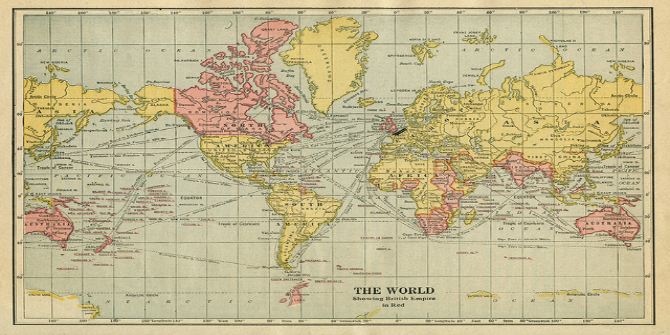

Universities generally seem much more concerned about their international connections than their local relationships. For many universities, the local context seems not to matter much to either their jet-setting VCs or their lecturers and researchers under pressure to produce REFable outputs in obscure journals.

Ok, that’s a bit of a parody, and doesn’t apply to all universities or all academics; but it’s how it often seems. In fact, it’s not as stark as that and there are many examples of universities engaging well with local communities. But they could do more and could do it better.

We’ve been looking particularly at how universities can support local disadvantaged communities (full report here). It’s very clear that universities have a lot to offer. A university can be a fantastic community resource. These are well-resourced institutions; they are spread across the country and aim to be of public benefit. They have expertise and some great facilities. Surely, you might well argue, they should be reaching out to local communities, particularly those that are under-resourced and under pressure?

Well, we found that most universities do get involved in local issues and do want to support local community development. But it’s sometimes not very visible and not a big priority.

One of the most important ways a university can link up with local communities is through Widening Participation — encouraging and supporting young people from poorer backgrounds to apply to university. A fair amount of effort has gone into that and it has worked – at least to some extent. But it’s also about taking education into the community – in a sense, reinventing extra-mural education. There’s a lot to be done there, and there are some good examples in our report of such outreach activity. In addition, universities could do far more to open up their facilities on campus, perhaps especially their sports facilities and arts provision.

We’ve looked also at student and staff volunteering. Student volunteering is one of the great success stories of university – community relationships. Most universities have well-developed student volunteering schemes that contribute a great deal to local communities. Not so many have staff volunteering schemes; there’s a lot of scope for development there.

A point to stress is that the best relationships are two-way, mutually beneficial. It’s not about the university distributing favours and largesse. For instance, universities that provide students with community placements find that both the students and local groups benefit from that. And it breaks down barriers. It’s the same with academic research and student and staff volunteering.

It’s surprising, really, how little research is done by academics working with communities rather than on them. We’ve found some heartening examples, but there just aren’t enough of them. It’s especially troubling that it’s still the case that academics doing locally-based research often feel it is undervalued, even despite the new emphasis on ‘impact’. Research that is based on co-inquiry and commitment to supporting disadvantaged communities all too often takes place despite the university, rather than being encouraged by it. Those researchers that are trying to do relevant, locally sensitive and committed work can be regarded as eccentrics who don’t know what’s good for them and their careers.

The Beacons initiative has helped to give some impetus to the idea of the ‘engaged’ university and there certainly have been some positive developments. But in many cases, local community groups would struggle to find the right person in their local university to help them. Universities can be pretty impenetrable, and hopeless at dealing with enquiries from people trying to find a way in. Likewise, academics who might well gain much from working with local communities often can’t find their way out of the institution. They don’t know who to approach, how to go about it.

We’ve sought to show what can be done and to challenge the less active universities to emulate those that are doing much more. There’s a lot of scope for sharing good practice across the institutions.

We also want to challenge the university sector as a whole to be more creative and more ambitious. Universities can play a local leadership role, promoting debate about challenges facing their area and ensuring, in particular, that the voices of disadvantaged communities are heard and taken into account. In addition, it’s important to remember that universities are big employers – and could be proactive in recruiting local unemployed people. Imagine if all universities committed to paying the Living Wage?

Universities need to be more open and more responsive to local need. They need to recognise that, especially in these tough times, they have much to give – and much to gain.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Fred Robinson is a Professorial Fellow at St Chad’s College, Durham University. His research has included work on urban and regional regeneration, the governance of public policy, and developments in the voluntary and community sector. He has worked with many local community organisations in North East England and helped to set up Durham University’s staff volunteering scheme.