Several big economic shocks and challenges are arriving all at once following Brexit and the pandemic. Tackling these means facing up to the UK’s strengths and weaknesses and having a coherent plan to intervene, writes Steve Coulter.

Several big economic shocks and challenges are arriving all at once following Brexit and the pandemic. Tackling these means facing up to the UK’s strengths and weaknesses and having a coherent plan to intervene, writes Steve Coulter.

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) over a decade ago was a massive shock with lasting consequences for incomes and public spending. Now, the UK faces several GFC-size economic shocks all at once. From COVID-19 and Brexit, to the climate crisis and dealing with technological change, and to the slower-burning issues of low productivity and regional disparities, the challenges are unprecedented in their urgency and severity. Do politicians have a plan for dealing with them? If not, what should one look like?

The government clearly grasps the magnitude of the COVID-19 challenge and has used the full weight of the state to preserve jobs and businesses during the pandemic. It understands, at a visceral political level at least, the need to ‘level up’ left-behind areas of the country and restore productivity and real wage growth. It senses the economic importance of technology as well as the urgency of decarbonising the economy and society. Some recent policy announcements, such as the new applied research agency (based on the US institution, DARPA, which developed the internet) are eye-catching and ambitious.

But it’s not at all clear whether there is any underlying vision behind all this, nor much in the way of a coherent strategy for addressing it. The government is still in denial about the long-term impact of Brexit on exporters. Its newly unveiled ‘Plan for Growth’ assumes a recovery in productivity growth which the Office for Budgetary Responsibility is not expecting in its budget forecasts.

With the economy at a crunch point, the UK’s entire economic model needs renewal. Yet the new Business Secretary, Kwasi Kwarteng, has chosen this moment to abandon the Industrial Strategy enacted just four years ago. The Plan for Growth, its replacement, looks neither a proper strategy, nor likely to do much to boost growth. Ditching the industrial strategy will regrettably confirm what a lot of companies and investors probably already suspected – that it is unwise to expect any UK government to stick to a program of supply-side reform for more than a couple of years.

The UK has generally got away with muddling through economic crises in the past. But the scale of the current challenges makes this approach inadequate this time. Of the two most immediate forces impacting the economy, COVID-19 and Brexit are especially dangerous as they are complementary shocks. Brexit does great damage to high productivity export sectors while COVID-19 hurts the employment-rich domestic service sector.

These shocks come on top of a set of legacy issues like weak productivity growth and regional inequalities. Productivity grew at its lowest rate for 250 years in the decade since the GFC, producing a corresponding slump in incomes. The country also stands out among large OECD economies in the extent to which productivity problems are regional rather than sectoral, and the degree to which productivity spillovers are not transmitted between the core and periphery of the economy. It is very sectorally and geographically unbalanced, with London far more reliant on service industries than other regions and far more integrated into global markets.

The UK may be very good at generating jobs, but not nearly enough of these are the skilled, high-paying ones that people want. Andy Haldane of the Bank of England estimates that 10m people are on insecure contracts. Further out loom other challenges. The technological revolution continues to upend old business models. While technology raises growth and productivity in the long-run, automation and ICT-enabled offshoring can produce disruptive labour market insecurity in the short term. Decarbonisation, meanwhile, could hit firms in the pocket just as they are struggling to raise the cash to invest, although it also presents economic opportunities in the longer-term.

Time for a plan

With this enormous problem-load, the UK needs a concerted efforts to shift more of its economy into innovative, higher-productivity sectors that build on existing strengths and mesh with areas of likely growth in global demand.

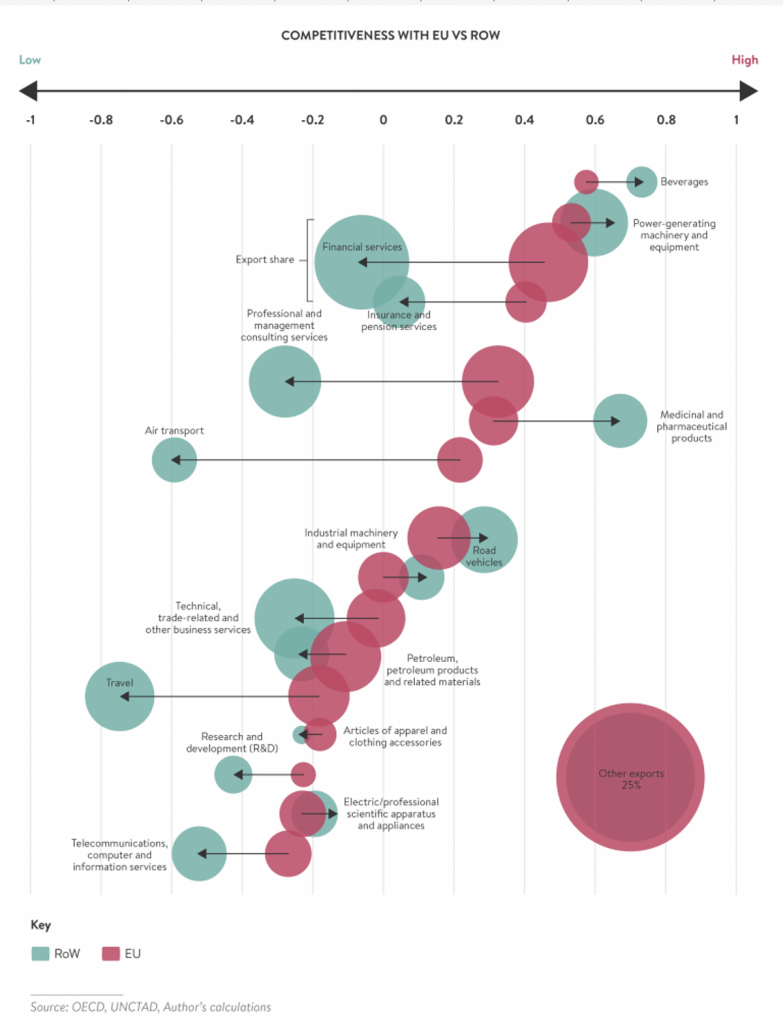

In our new report from the Tony Blair Institute, myself and Christina Palmou analyse the relative competitiveness of UK economic sectors in comparison with the EU and rest of the world (RoW) markets using symmetrical revealed comparative advantage (see chart below). We find that key sectors like business and financial services – the workhorses of recent prosperity and export earnings – are less competitive with RoW compared with the EU. Other sectors, such as cars, are slightly more competitive in terms of higher export shares, with RoW. But this will be undermined by likely supply chain disruption arising from increased border friction with continental suppliers. Medicines, however, are an area of clear strength where demand from India and China for therapeutic drugs could soar in the future.

Our conclusion overall is that the country needs to shift away from heavy reliance on financial services (which don’t provide enough good jobs and will suffer outside the EU) and towards high-technology industries where the UK has some comparative advantages, are not so clobbered by the negative effects of distance on trade, and where significant future market opportunities lie.

Achieving this requires concerted and coordinated policy effort in multiple fields. The government will need to drop its opposition to industrial policy and be prepared to intervene to encourage industries to enter risky new markets like EVs and AI. Vaccine development demonstrates how sectoral intervention through the ‘Sector Deals’ in the 2017 Industrial Strategy can achieve stunning success. The UK has not always covered itself in glory when trying to do industrial policy. Now is a pretty good time to put that right.

___________________

Steve Coulter is Head of Industrial Strategy, Skills and Sustainability at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, and a Visiting Fellow in the LSE’s European Institute where he previously taught.

Steve Coulter is Head of Industrial Strategy, Skills and Sustainability at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, and a Visiting Fellow in the LSE’s European Institute where he previously taught.

Photo by Greg Rosenke on Unsplash.