Ministers clearly believe that harsh sentences for those convicted in the recent disorder, and the arrest and prosecution of those involved (even in minor ways)will create strong disincentives for future potential rioters. The government has also found like-minded judges, magistrates and prosecutors to give added impetus to this push in the immediate riot aftermath. But Chris Gilson points to voices suggesting a significant downside. Sentences that are disproportionate for the offences that have taken place will likely be overturned. And enforcing ‘collective punishments’ on whole households by removing benefits and social housing for the families of those convicted may be hard to enforce and is legally dubious. Allied with aggressive post-riot policing, such tactics may only exacerbate existing tensions in high-stress urban areas.

Ministers clearly believe that harsh sentences for those convicted in the recent disorder, and the arrest and prosecution of those involved (even in minor ways)will create strong disincentives for future potential rioters. The government has also found like-minded judges, magistrates and prosecutors to give added impetus to this push in the immediate riot aftermath. But Chris Gilson points to voices suggesting a significant downside. Sentences that are disproportionate for the offences that have taken place will likely be overturned. And enforcing ‘collective punishments’ on whole households by removing benefits and social housing for the families of those convicted may be hard to enforce and is legally dubious. Allied with aggressive post-riot policing, such tactics may only exacerbate existing tensions in high-stress urban areas.

From the Prime Minister downwards, the government clearly feels that it must demonstrate in unequivocal ways that it has restored order after the biggest outbreak of social disorder in Britain in the last 30 years. Publicizing strong disincentives for those who might be keen to repeat recent riotous behaviour has been the dominant theme from the outset. Yet, punitive strategies have already caused alarm in some cases. On Wednesday morning, the Howard League for penal reform warned that the rush to send out a message on law and order was leading to some ‘bad sentences’, that appear completely disproportional when set against other offences. And in a recent speech on the riots, Ed Miliband warned of the dangers of ministers adopting “knee-jerk gimmicks” in order to be seen to grapple with the problem.

Disincentives

In a near simultaneous speech to Ed Miliband’s on Monday, David Cameron spoke of both a security and a social ‘fightback’, going beyond keeping 16,000 police on the streets of London last week. Its measures seem to be twofold; a stronger line on criminals and criminal punishments, and additional civil punishments to remove the benefits of those found guilty of rioting.

Since the riots subsided last week police have been continually raiding houses across London and other English cities, aggressively stoving in the doors of properties, arresting hundreds of people (1,700 in London alone since the riots) and recovering large amounts of stolen property. Theresa May has also mooted plans for the police to be able to impose curfews on specific areas to clear the streets. And soon after Cameron’s speech on Monday, Her Majesty’s Courts and Tribunals Service listened to his pledge for tough punishments, and gave advice that local magistrates should disregard their normally short sentencing guidelines, and instead, refer cases to the Crown Courts. The government’s intended message here is loud and clear: if you have participated or benefited from the riots, we will find you, arrest you, and ensure that you go to jail for a significant period of time.

New, civil law punishments are also now in play. Last Friday, Wandsworth Council in London, served one of their Battersea tenants with an eviction notice – not because the tenant herself had participated in the riots, but because her son had been charged with (but not convicted) of doing so. In a similar vein, on Monday morning, the Work and Pensions Secretary, Iain Duncan-Smith told the Today programme:

‘We already accept that if people who are receiving benefits do not.., are not prepared to seek work.., [do not] take the work that’s available to them, we take the benefit off them. And if you go to prison we take your benefit off you. So what we’re looking at is:”For criminal charges, should we take the benefit?” And the answer is: “Yes”’.

The risks to legitimacy in distorting normal sentence tariffs

The post-riot strategies have had some impressive results in terms of the numbers of arrests made, and clearly meet the Conservatives’ urgent political need to being seen (after such an extraordinary lapse) as ‘tough on crime’. But there may also be significant downsides to these polices, that will surface strongly in the near future.

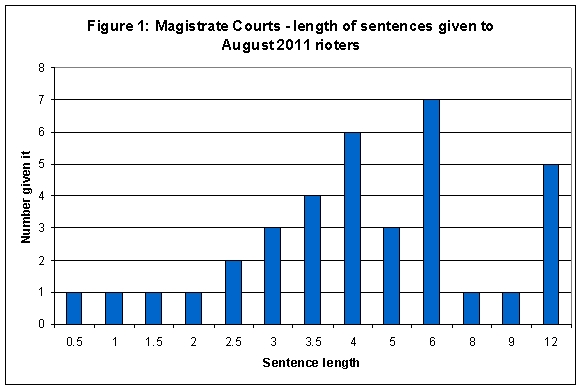

Already there is more than anecdotal evidence that the sentences for those convicted of crimes in riot contexts have been appreciably longer than they otherwise would be for the same offences outside of these events. Preliminary results from the Guardian of those sentenced in Magistrate Courts show that most sentences are around 4- to 6 months in prison.

Source: Guardian DataBlog

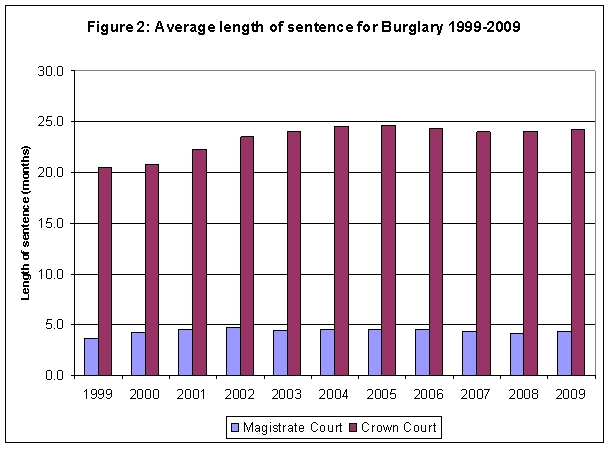

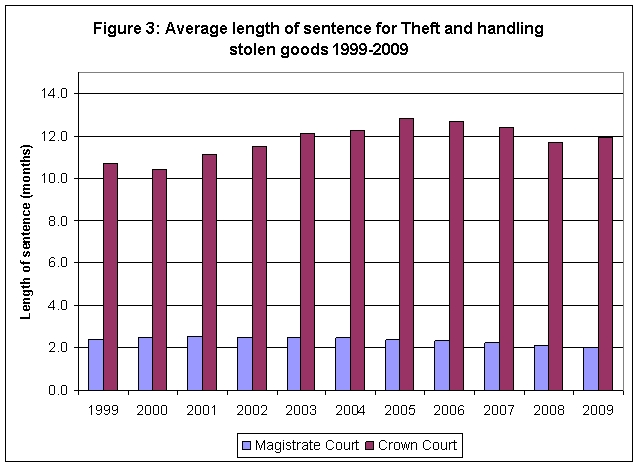

If we look at sentencing up until now for the type of offenses that the rioters are being convicted of, such as burglary and the theft or handling of small amounts of stolen goods, the logic of bringing in Crown Courts sentences is clearly to allow much harsher, more punitive sentencing.

Source: ONS sentencing statistics

Source: ONS sentencing statistics

For both types of offence, Crown Court sentences are, on average, about six times longer than those in magistrates’ courts. Anecdotal evidence also shows that the police and CPS are pushing hard for longer sentences and meeting a ready response. In one example of ‘tough’ sentencing, a Manchester woman was jailed for 5 months for receiving a stolen pair of shorts. In another case two northern men who posted messages inciting people to riot in Warrington), without any such result in fact occurring, were each sentenced to four years in prison at Crown Court.

An important element of justice is that it should be clearly perceived as fair and equal for all – a core element of legitimacy may be imperilled if but much harsher punishments are handed out for offences linked in any way (however loosely) to the disorder. John Cooper QC told Newsnight last night, that it would be very likely that some recent longer sentences would be overturned at the Court of Appeal. But in riot-hit localities, the damage to perceived legitimacy may already have been done, and policy-community relations ratcheted downwards accordingly.

A push to ‘collective punishment’?

The support from David Cameron, Ian Duncan Smith and other ministers for benefits and social housing to be withdrawn from individuals associated with rioting appears to have other dangers, of envisaging a form of collective punishment exacted from the households of those involved. Those immediately responsible will go to prison and their families may lose their homes and benefits. Those immediately convicted of offences may thus be punished twice, while the lives of other household members could be damaged without any reason in ways that may also prove legally dubious, coming up against welfare law and the European Convention on Human Rights, which prevents retrospective punishment for crimes.

Achieving community reunification

Divisive policies that risk undermining the perceived impartiality of justice and worsening policy-community relations for short-term or party-political gains are especially unlikely to be helpful for the social cohesion of communities where riots happened. A Brixton local, Michael Ibitoye, was interviewed by BBC News in Ealing last Friday night:

I believe that opportunity’s key. I believe that maybe a lot of us feel that we don’t have enough opportunity, and I’m talking opportunity, in a work, study, and just business life. A lot of people come to me with ideas, and there’s no-one to pass on the message to. You understand? So we need key communication – we need someone to be able to communicate to, to allow opportunities. Otherwise people will go and loot, because that’s the opportunity available to them, even though it’s a negative opportunity.

Harsh sentences and police tactics will also risk reinforcing the adversarial relationship that the police already have with many people within the riot-torn communities. Just as the current outbreak spread from a single point of tension in Tottenham, the mishandling of the aftermath of the shooting of Mark Duggan, so it may be severely counter-productive to assume that a trail of broken-down front doors, disproportionate sentences for apparently minor crimes, and politically inspired collective punishments of whole households is not likely to sow the seeds of future discontents more than it creates disincentives for future disorders.

Please read our comments policy before posting.