Support for the EU has fallen in several European countries since the beginning of the financial crisis. Han Werts, Marcel Lubbers and Peer Scheepers assess the political effects of this rise in Euroscepticism using data from the European Social Survey. Their analysis shows that the probability of voting for radical right-wing parties increases substantially with levels of Euroscepticism.

Support for the EU has fallen in several European countries since the beginning of the financial crisis. Han Werts, Marcel Lubbers and Peer Scheepers assess the political effects of this rise in Euroscepticism using data from the European Social Survey. Their analysis shows that the probability of voting for radical right-wing parties increases substantially with levels of Euroscepticism.

In many European countries, a notable decline in political and public support for the European Union has been observed. There is also some evidence from Eurobarometer studies that the recent economic crises in Greece and Cyprus and the unstable economic situation in the other Southern European countries has decreased support for the European Union further and vice versa has increased Euroscepticism.

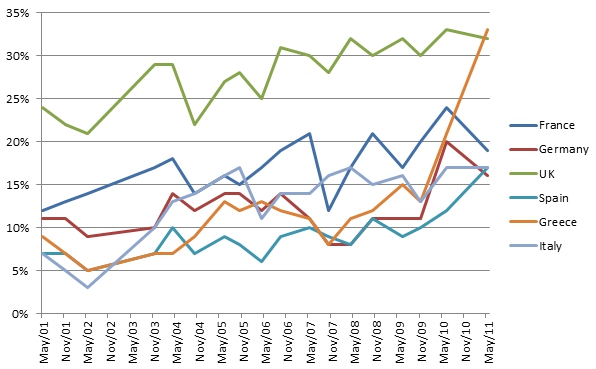

As Figure 1 shows, the populations of Greece, Italy and Spain contained only small proportions that evaluated membership of the EU as ‘a bad thing’, certainly compared to the UK: they actually were among the lowest in Europe, with figures below 10 per cent from the turn of the century on. However, since the start of the economic crisis, these proportions have increased in Italy and Spain to 17 per cent in 2011, and even to 33 per cent in Greece. However, Euroscepticism is also now more widespread in countries like France, the UK and Germany than it was 10 years ago. In 2005, the popular rejections of the Constitutional Treaty in France and the Netherlands showed that numerous citizens are hesitant about supporting further European integration.

Figure 1: Percentage of citizens that view membership of the EU as a ‘bad thing’

Source: Eurobarometers 2001-2011 – Eurobarometer interactive search system

All across Europe, we have witnessed radical right parties successfully mobilising national identity considerations against the European Union. In several European Parliamentary elections in recent years, radical right-wing parties in particular have used the rhetoric of anti-EU sentiment and, paradoxically, gained seats in the European Parliament. These parties see further integration into a political European Union as a threat to the sovereignty of the nation state: nearly all radical right-wing parties agree that the EU is bad and should be either reformed fundamentally or abolished. Yet, the issue of how relevant Euroscepticism is for the general EU public in terms of voting for radical right-wing parties in contemporary Europe has received little empirical attention in previous studies.

In a recent study, we focused on the relationship between Euroscepticism and radical right-wing voting in national elections in 18 European countries between 2002 and 2008. We took advantage of high-quality cross-national European data selected in the European Social Survey programme. These are surveys that are conducted under the highest scientific standards. We included only those countries with a radical right-party. First, we focused on social cleavages in radical right voting, e.g. social class and religiosity. Second, we examined the effects of several contextual characteristics, such as the economic situation and the level of migration. Third, we took diverse socio-political attitudes into account, among which we had a focal interest in the role of Euroscepticism. We tested whether Euroscepticism affects voting for the radical right, over and beyond other relevant attitudes of the voters that have previously been proposed to determine radical right-wing voting.

We found evidence that Euroscepticism indeed contributes to the explanation of voting for the radical right, beyond the huge effects of perceived ethnic threat and political distrust. Euroscepticism turned out to be a key political motive, actually the third-strongest socio-political determinant, to explain radical right-wing voting in Europe. The effect of Euroscepticism is, however, relatively smaller than of perceived ethnic threat and political distrust. Moreover, while perceived ethnic threat does well in explaining why particular social categories, i.e. lower educated people, manual workers, unemployed people and non-churchgoers are more likely to vote for the radical right than others; Euroscepticism hardly explains these differences. Figure 2 shows the relationship between Euroscepticism and the probability of voting for a radical right-wing party.

Figure 2: Probability of voting for a radical right-wing party by level of Euroscepticism

Source: European Social Survey (2002–2008); own calculations (based on MLWin parameters).

What do these findings imply? One of the expectations may be that political parties that identify and magnify political issues (possibly) indicating institutional weaknesses of the EU – and on this issue radical right-wing parties are dominant – may get even more electoral ground, since the euro and the EU in general are suffering from economic weakness. Whereas some mainstream political parties tend to support greater integration, political parties on the flanks emphasise that more powers should be returned to national governments. Moreover, we expect that Euroscepticism, contemporarily fed by the economic and financial crisis around the euro and political debates on the EU budget, as in the recent cases of Greece and Cyprus, may attract more voters to radical right-wing parties, as Euroscepticism may rise even further.

However, radical right parties cannot be overly optimistic with this scenario. The Dutch 2012 elections have shown that playing the anti-Eurosceptic card during economic hardship may function like a boomerang. Economic crises tend to shift the focus to the economic domain, stimulating a confrontation between right and left-wing politics in the classical meaning: between those in favour of austerity measures and those opposing it. Previous research has suggested that the radical right gains less from economic downturns when the political salience of the economy in left-right terms increases, at the cost of cultural and identity related concerns. Still, our research shows that radical right-wing parties gain electorally by Euroscepticism. We expect that due to further EU enlargements and increased migration from new EU member states to the richer EU member states, because of the crisis around the euro, and because of debates around the budget of the EU, Euroscepticism will turn out to be an even stronger determinant of radical right-wing voting in the near future.

This article was originally published on LSE’s EUROPP blog.

For a longer discussion of the topic covered in this article see: Han Werts, Marcel Lubbers, and Peer Scheepers (2013) ‘Euro-scepticism and radical right-wing voting in Europe, 2002–2008: Social cleavages, socio-political attitudes and contextual characteristics determining voting for the radical right’, European Union Politics, vol. 14 no. 2: 183-205.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/14uYLe1

_________________________________

Han Werts – Radboud University Nijmegen

Han Werts – Radboud University Nijmegen

Han Werts is a Policy Officer at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands.

–

Marcel Lubbers – Radboud University Nijmegen

Marcel Lubbers – Radboud University Nijmegen

Marcel Lubbers is Associate Professor in the Sociology Department at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands.

–

Peer Scheepers – Radboud University Nijmegen

Peer Scheepers – Radboud University Nijmegen

Peer Scheepers is Professor of Methodology and Social Science Research within the Faculty of Social Sciences at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands.

The survey was a surprise for me. I know that the support for the european union is bigger in the south of Europe than in the uk. But I hadn’t expected to see such high percentages even in Germany. I thought that the austerity policy under the leadship of Chancelier Merkel would lead to a stronger support of the EU in Germany.