It is five decades since Enoch Powell told a Conservative Association meeting in Birmingham that soon “the black man will have the whip hand over the white man”. Judi Atkins analyses the rhetoric of that speech and concludes that, although Powell’s notorious prediction of a race war has not materialised, his rhetoric of division and blame still forms part of British public discourse.

It is five decades since Enoch Powell told a Conservative Association meeting in Birmingham that soon “the black man will have the whip hand over the white man”. Judi Atkins analyses the rhetoric of that speech and concludes that, although Powell’s notorious prediction of a race war has not materialised, his rhetoric of division and blame still forms part of British public discourse.

On 20 April 1968, Enoch Powell delivered his now-infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech to a Conservative Association meeting in Birmingham. In an article for a forthcoming special issue of The Political Quarterly to mark its 50th anniversary, I analyse Powell’s address through the lens of epideictic (or ‘display’) rhetoric. This branch of rhetoric is traditionally associated with praise and blame, but scholars have broadened its scope to encompass the affirmation of a common identity.

At first sight ‘Rivers of Blood’ is antithetical to this conception of epideictic rhetoric, given that its purpose was to unsettle and divide. However, the application of a framework proposed by Celeste Michelle Condit shows that Powell’s speech is best understood an example of the epideictic of blame and exclusion.

According to Condit, epideictic rhetoric serves three functional pairs. The first is display/entertainment, whereby an orator’s eloquence may ‘entertain’ their listeners. Meanwhile, the second pair is definition/understanding, which refers to the speaker’s power to explain a troubling situation and so to provide reassurance. The third is ‘shaping/sharing of community’, which acknowledges the role of rhetoric in constructing a collective self-image and reinforcing a shared identity.

Powell began the speech by seeking to establish his authority. Thus, he told his listeners that ‘the supreme function of statesmanship is to provide against preventable evils’, the discussion of which is ‘the most unpopular and at the same time the most necessary occupation for the politician’. The unspecified ‘evils’ are, of course, the consequences of immigration and, by confronting this contentious issue head-on, he came across as a lone voice in the wilderness, warning the nation of the dangers ahead. By ‘saying the unsayable’, Powell did not so much entertain his audience as provide gratification by articulating their deep-seated concerns. Consequently, the speech acted as an (albeit temporary) outlet for the built-up resentment he believed was felt in areas that were experiencing high levels of immigration.

The ability to define a situation enhances the authority of a speaker, and Powell devoted much of his address to setting out the nature of the problem as he saw it. In particular, he predicted that unrestricted immigration would lead to ‘whole areas, towns and parts of towns across England [being] occupied by sections of the immigrant and immigrant-descended population’ by the year 2000. A key contributing factor was the government’s decision to allow an annual inflow of around 50,000 dependents, a move that Powell claimed was akin to ‘watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre’. This definition of the situation offered no reassurance to those concerned about immigration, while Powell’s vivid portrayal of a dystopian future served only to heighten public anxiety.

The shaping/sharing of community is achieved through public affirmations of communal identity. However, by emphasising some values and traditions over others, a speaker can exclude individuals or groups from their definition of community. So, to this end, Powell contrasted the nation’s treatment of immigrants with that of its own people:

While, to the immigrant, entry to this country was admission to privileges and opportunities eagerly sought, the impact upon the existing population was very different. For reasons which they could not comprehend, and in pursuance of a decision by default, on which they were never consulted, they found themselves made strangers in their own country.

To illustrate his argument, Powell claimed the native English ‘found their wives unable to obtain hospital beds in childbirth, their children unable to obtain school places … their plans and prospects for the future defeated’. Though he never stated it directly, Paul Chilton notes that the audience can plausibly infer that ‘the agents of change … are either the politicians criticised by Powell or the immigrants themselves’ [p. 123]. Irrespective of culpability the consequences were the same, namely the displacement and victimisation of the existing population, which fueled the in-group’s hostility towards immigrants and their fears for the future.

A striking feature of Powell’s rhetoric of exclusion was his use of the ‘anecdotal testimony of an “ordinary” person … as an authority and as a proof of a more general political point’. Thus, he repeatedly praised the ‘ordinary, decent, sensible [English] people’ who had voiced their concerns about immigration, and treated their stories as representative of what ‘thousands and hundreds of thousands are saying and thinking’. In one such conversation, Powell reported, a constituent said he wanted his children to settle abroad, claiming that ‘in 15 or 20 years’ time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man’. This view was consistent with Powell’s prediction that unfettered immigration would result in large swathes of England being ‘occupied’ by an ‘alien element’. In turn, the claim that the existing population would be subjugated served to foster division by presenting these ‘others’ as a direct threat to the nation and its way of life.

The legacy of Powell’s speech is mixed. His most notorious prediction – that unrestricted immigration would lead to a race war, which would see the streets of Britain ‘foaming with much blood’ – has not materialised and, according to Sally Tomlinson, the 86% of the settled population of England and Wales identified as ‘white’ in the 2011 census ‘presumably still [holds] the “whip hand”’ over the 14% who identify as Asian, Black or Mixed Race.

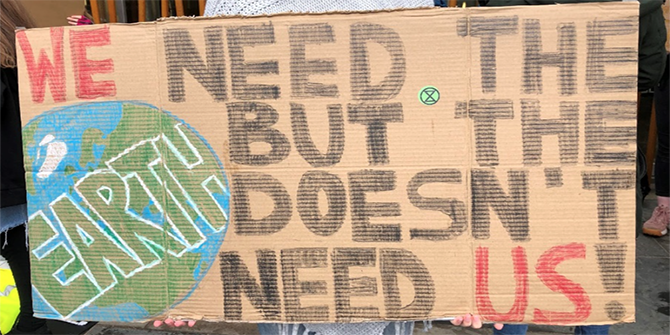

Nevertheless, the arguments of the Leave campaign prior to the EU referendum contained strong echoes of ‘Rivers of Blood’. A notorious example is UKIP’s ‘Breaking Point’ poster, which showed a winding queue of Syrian refugees in Slovenia in 2015. As Jonathan Jones explains: ‘This tide of faces summons up exactly the same swarms and rivers and hordes of otherness and racial difference that Powell spoke against in 1968 and that so many have tried to evoke since’.

Campaigners also reiterated Powell’s argument about the impact of immigration on the existing population, with Priti Patel claiming that ‘the shortage of primary school places is yet another example of how uncontrolled migration is putting unsustainable pressures on our public services’. This rhetoric of division and blame was widely condemned but, with rising anti-immigrant sentiment and the uncertainties surrounding the UK’s departure from the EU, it is likely to feature in the public discourse on ‘race’ and immigration for some time to come.

______

Note: the above draws on the author’s forthcoming article for The Political Quarterly, entitled ‘“Strangers in their own Country”: Epideictic Rhetoric and Communal Definition in Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” Speech’.

Judi Atkins is Senior Lecturer in Politics in the School of Humanities at Coventry University. She is author of Justifying New Labour Policy (2011) and Conflict, Co-operation and the Rhetoric of Coalition Government (2018), as well as several articles on the relationship between ideas, language and policy in British politics.

Judi Atkins is Senior Lecturer in Politics in the School of Humanities at Coventry University. She is author of Justifying New Labour Policy (2011) and Conflict, Co-operation and the Rhetoric of Coalition Government (2018), as well as several articles on the relationship between ideas, language and policy in British politics.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Why are we giving prominence to a discredited racist politician where what he predicted has not happened but will relight the sentiments of the far right and give them a voice which has long since been buried?

Leaders should never create any division between Whites or Non-Whites or inter-ethnic groups. Leader’s job is to unite people and create a social cohesion and to unite people so that they live with kindness, caring, compassion and live side by side and live together and grow together.

When we all thrive the society thrives. If not we create ‘them and us’ culture and in such a culture and such a nation, eventually everyone suffers. When any society suffers due to war or any man-made crisis or any crisis, it is usually the sickest, vulnerable, unemployed and poor people suffer the most.

Today, Britain is a divided nation. Rich versus poor, north versus south, Labor versus Conservatives and interethnic discrimination and also inter Tory or inter-labor divisions are so common.

Brexit is a wake-up call to all of us and to the British society. We have created ghettos and even today, multi-cultural Britain still has uni-cultural leadership.

NHS reflects the society. Today, in NHS 40% of doctors are Non-White and 25% of nurses are Non-White but if one looks at the key decision makers or CEOs, or Nurse or Medical Directors or any senior leaders, a vast majority of them are White! In NHS women are much better represented in leadership but it is White women!

If we want UK to be a strong nation and great nation then we must appoint right leaders from right pool of people and if not, we will appoint weak leaders and poor leaders who do not challenge the current leadership and nothing much will change!

Today, NHS is in crisis and with Brexit, our great nation will be in crisis and it is up to us as citizens of this great nation to show how to build a great nation.

We must control immigration. We must allow immigration only on the basis of what the country needs but we must create our own workforce to have the necessary skills so that our own people are appointed, have a job and are able to do a good job and we create a culture of staff happiness and good team working so that productivity increases and the nation has enough money to spend on NHS, Police, to stop crime and we can have an excellent education and training system.

A good leader has a clear vision and he/she makes that vision as the dream of the nation and inspires motivates and transform the nation by empowering people of this great nation. Gandhi, Mandela were the great leaders. Saddam Husain suppressed his subject and made all of them as followers and today one has to look at the state of Iraq, Syria and many other nations at war with each other.

We need great leaders who can create a great team of leaders and transform the nation and to do so, we need diversity in leadership and we got to include all the citizens of this nation. The sense of belonging is the most important sense for human beings.BMEs will have a sense of belonging to the nation when they are valued, respected and treated equally and it is also important to have accountability for all leaders so that if they bully, harass and victimize any staff they are held to account.

Leadership with authority but without any accountability is the most dangerous form of leadership is the World.

Hear, hear!