Patrick Ainley argues that widening participation to higher education has not led to fair or equal access to higher education or outcomes in the labour market as systemic inequalities have deepened between institutions and subjects. System-wide reform is therefore necessary as well as larger societal change.

Patrick Ainley argues that widening participation to higher education has not led to fair or equal access to higher education or outcomes in the labour market as systemic inequalities have deepened between institutions and subjects. System-wide reform is therefore necessary as well as larger societal change.

Fifty years ago the Robbins Report on higher education initiated a phase of progressive reform to change society through education. Robbins recommended expansion of HE beyond the limited pool previously considered educable to all ‘qualified by ability and attainment’. Robbins thus preserved a selective system and was not an entitlement or even expectation of HE for all who graduated high school as in the republican French and original US model. Following Robbins, the official introduction of comprehensive schools from 1965 was not accompanied by curricular reform so that comprehensives still competed for selective university entry with the surviving grammars and private schools on the uneven playing field of academic A-levels.

Primary schools were, however, freed for child-centred education and there was also growth of further education (FE). Unlike 11+ selection, which became a thing of the past in 80% of English secondary schools, reforming state education at all levels aimed to demolish class divisions by opening equal opportunities to all. The logic of comprehensive reform carried forward to inclusion of children with special needs, a common exam at 16 and a National Curriculum presented as universal entitlement, as well as – from 2003-11 – widening participation in HE to nearly half of 18-30 year olds.

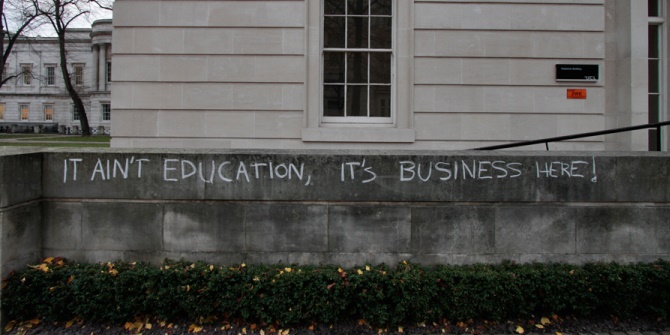

This period of attempted reform has been ended by the 2010 Browne Review and the following White Paper. Now a market-driven Great Reversal to a minority HE is intended as education teaches young people their place and aims to keep them there. Instead of the limited upward social mobility from the working to middle class that existed in a growing economy and expanding welfare state after the war, even young people who succeed in education today find ascent difficult because most mobility is downwards. This reality is disguised by, on the one hand, reinventing oversubscribed ‘apprenticeships’ that employers don’t want and, on the other, reintroducing ‘a grammar school education for all’ – if not grammar schools themselves and/or vouchers plus privatized state schools – alongside colleges and universities for which fees function as de facto vouchers.

So what went wrong?

Despite Bernstein’s well-known warning that Education cannot compensate for society, teachers thought it could. This was partly because of their own experience of HE which grew from c.2%, mostly young men, after the war to c.7%, including a growing proportion of women, by the time the baby-boomers attended university in the late 1960s. This was a generation most of whose parents – even if middle class – did not themselves go to university but these students’ HE experience made them middle class if they were not already.

The new universities aimed to spread traditional HE in the arts, humanities and social sciences, while extending redbrick Humboldtian sciences to the Colleges of Advanced Technology. Instead of more Robbins universities, the polytechnics from 1965-1992 aimed at both an HE on the cheap and an alternative HE for adult students living locally. Despite some brave experiments, this proved illusory. So too did the latest phase of widening participation to HE sustained on a reduced unit of resource by more illusions, this time in the transformative powers of new ICT to include nearly half of 18-30 women at least – now fallen to c. one third of 18+ women and a quarter of men.

Vocationalism, which was originally deployed as a progressive critique of ‘irrelevant’ academicism, was appropriated in the 1980s by claims for the vocational relevance of the youth training that substituted for the collapse of industrial apprenticeships in the 1970s. From there its language of ‘skills’ permeated all levels of learning until Mrs Thatcher could declare to her last Party Conference that the battle for the economic future would be won ‘in Britain’s classrooms’ by teaching the future generations of workers to spell properly! Similarly, the latest curricular revanche announced to the House of Commons by Michael Gove on 11/6/13 effectively held the examinations system responsible for the UK economy’s ‘failure to compete’ with Pacific Rim countries.

As for research, universities are shifting from being guardians of national knowledge to ancillaries in the production of knowledge for global corporations. Research selectivity has concentrated funding and restructured the system. In a new mixed economy, private sector penetration of increasingly entrepreneurial public universities is perverting the 1918 Haldane principle that public research funding should be allocated on the basis of academic criteria, not political or economic considerations.

Combining a free market with strong central control, the new market-state introduced since 1979 is exemplified in English education, changed from being a national system of schools and colleges locally administered to a national system nationally administered and including universities. It operates on the principal that power contracts to the centre whilst responsibility is contracted out to semi-privatised but state-subsidised ‘delivery units’, as the schools, colleges and universities have become. However, with the important exception of £1,000 a year fees, introduced for home undergraduates in 1997 and subsequently twice tripled, most services remaining in the public sector were not monetized; nor were they privatized by New Labour. In fact, state spending on education, particularly on schools, was increased by the Blair-Brown governments.

Widening participation to higher education has not led to fair or equal access to higher education or outcomes in the labour market as systemic inequalities have deepened between institutions and subjects. Like Thatcher’s previous encouragement of home ownership, this presented itself as a professionalization of the proletariat whilst disguising a proletarianisation of the professions. Far from a ‘knowledge economy’, automation leading to deskilling and outsourcing have infiltrated the employment hierarchy to undermine previously secure professionals, including academics.

Meanwhile, student motivations become increasingly instrumental as they will do anything they have to to get the grades they need. Even becoming indebted up to £27k+living expenses in hopes of the 15% higher lifetime earnings than people without degrees that the Million+ group of former-polytechnic universities estimate as their ‘graduate premium’ for one of the c.40% of occupations that have reportedly become ‘graduatised’, bumping other less qualified applicants further down the jobs queue. This is corroding relations between teachers and taught as lecturers are also locked into a simulacrum of learning as students run up a down-escalator of inflated qualifications.

So what are the alternatives?

The market is so omnivorous that alternatives, like efforts at Lincoln University to do away with grading, tend to get assimilated as brands if they are successful. System-wide reform is therefore necessary as well as larger societal change. Peter Scott is surely right to call for ‘a revival of radical thinking about HE’, whilst accepting that ‘HE needed reform but not this reform’. Therefore to celebrate and not apologise for a mass system and fight for an increase in student numbers not ‘consolidation’ – ‘the job is only half done!’ This is not to demand everyone necessarily attends HE at 18+ but that there is a universal right to do so based on a general certificate of high school graduation. This will require relating schools and colleges to universities in regional learning infrastructures.

This does not preclude dedicated research institutes such as already exist in this and other countries, especially for ‘Big Science’, but in general, teaching should be combined with research as a means of introducing students to an academic community that critically learns from the past to change behaviour in the future. Such development will widen the still available critical space afforded by HE in which a defence of the public university built up since Robbins can be conducted.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Patrick Ainley is Professor of Training and Education at the University of Greenwhich and co-author with Martin Allen of The Great Reversal, Young People, Education and Employment in a Declining Economy from www.radicaled.wordpress.com.

Professor Ainley,

I was linked to this article from the CDBU. I have been developing an alternative model for HE, based on the professional model used in law, accounting, engineering and other sectors.

The website link I have provided is to the latest presentation of the model.

I hope that you have time to read it and find some use in it.

Thank you,

Shawn Warren PhD