Although reaction to the recent Supreme Court ruling on the triggering of Article 50 has focused on arguments about the sovereignty of parliament, for Scotland it has highlighted once again not that parliament is sovereign, but that the Westminster Parliament is – and that this rule applies even if Westminster intends to legislate contrary to Scottish wishes. Sean Swan explains why recent events have brought into sharp focus the broader weaknesses of Scotland’s constitutional position.

The Supreme Court ruling on whether the triggering of Article 50 required an Act of Parliament was a thing of paradox. Many people who might normally be assumed to favour popular sovereignty went into ecstasy over a ruling which was essentially a Diceyan reassertion of the sovereignty of parliament. Remainers embraced this sovereignty of parliament simply because the referendum – which they lost – had been an exercise in popular sovereignty. But these were English issues. Viewed from Scotland, the ruling carried a different message, not about whether sovereignty lay with the people or with parliament, but about which parliament was sovereign.

The Scots had hoped that the case would lead to a ruling supporting Nicola Sturgeon’s position that Brexit could not proceed without the consent of the devolved nations. Although the Scottish Government was not party to the case, there was an intervention in the devolution aspect of it by the Lord Advocate on behalf of the Scottish Government. The point of law, at least in relation to Scotland, turned on to the Sewel Convention, which ensures that before legislating on devolved matters, Westminster will normally seek the express agreement of the Scottish Parliament.

The Supreme Court judgment recognised that the Sewel Convention had received ‘statutory recognition’ through its inclusion in the recent Scotland Act (2016), but added that had UK Parliament intended to convert it into a legal rule, they would have worded the relevant clause accordingly.

In other words, its inclusion in the Scotland Act gave the Sewel Convention ‘recognition’ but no legal effect. Even the Bill of Rights was quoted to prove that the convention could not be enforced by any court. And although three judges dissented on the main issue of the need for a vote in Parliament to trigger Article 50, not a single judge dissented in relation to the reasoning behind excluding the Sewel Convention.

No surprises here. Every mention of the convention – whether in Parliament, law or memoranda of understanding – is prefaced by or ringed with, caveats implying or boldly asserting the right of Westminster to legislate on any matter in Scotland, devolved or not.

The Sewel Convention is not a Scottish version of the Statute of Westminster. The Supreme Court’s ruling was a reassertion of a basic fact of the British constitution: the sovereignty of Westminster, while Scotland’s (denied) right to veto Brexit was considered in terms of ‘devolution legislation’, ‘devolution arguments’ or ‘devolution issues’. ‘Devolution’ is the key term. The Scottish Parliament is not a sovereign body. Such powers as it has are simply powers devolved upon it from Westminster, the sovereign parliament.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon’s reaction to the decision was to assert that even if there was no legal requirement for Westminster to seek the approval of the devolved governments prior to triggering Article 50, there is still a “clear political obligation to do so”. She is absolutely correct, but it absolutely will not happen. The Westminster Government is fully aware that if they gave the Scots the power to veto Brexit, they would use it; but, following the Supreme Court ruling, there is no legal requirement for London to give Scotland any such power.

Speaking after the Supreme Court judgement, the First Minister stated that:

The claims about Scotland being an equal partner are being exposed as nothing more than empty rhetoric and the very foundations of the devolution settlement that are supposed to protect our interests – such as the statutory embedding of the Sewel Convention – are being shown to be worthless. This raises fundamental issues above and beyond that of EU membership.

Sturgeon then raised the possibility of a second independence referendum. But she has not, yet, committed to holding one. Her reticence does not spring from any lingering affection for the UK state. The problem she faces is, as Gordon Wilson, former leader of the SNP explained:

The opinion polls show no movement in support for independence. It is almost as if the Scots people, through exhaustion, are in a catatonic trance. And yet there are calls for a gamble on a second referendum without adequate preparation. The Yes vote is just as likely to decrease as to surge. It defies common sense.

But Nicola Sturgeon has never been short of common sense. The dilemma she faces is that despite Brexit, the latest polls show support for independence has barely increased since 2014. And this has been consistent since the Brexit referendum. Sturgeon cannot risk losing a second independence referendum – it would put Scottish independence back by a generation.

Yet Scotland’s position within the UK is intolerable. Under the British constitution, it is irrelevant that 57 of Scotland’s 59 MPs are opposed to Brexit; irrelevant that Scotland voted two to one against Brexit; and irrelevant that Brexit is opposed by the parliament and government of Scotland. Regardless of whether or not there is a majority in favour of outright independence, the status quo reduces democracy in Scotland to a mockery in which neither (Scottish) popular nor (Scottish) parliamentary sovereignty apply.

Nor would any future ‘federal’ UK change this. Membership of the EU, like nuclear weapons and wars in the Middle East, is a matter of foreign policy, and foreign policy is invariably a matter reserved for central government, even in federal systems.

The logic of this situation may force the First Minister to opt for the gamble of a second Indyref. In any event, it is clear that Scotland’s current constitutional position is a democratic outrage. This is what Brexit in general, and the supreme court case in particular, has brought into sharp focus.

_____

Sean Swan is a Lecturer in the Department of Political Science at Gonzaga University.

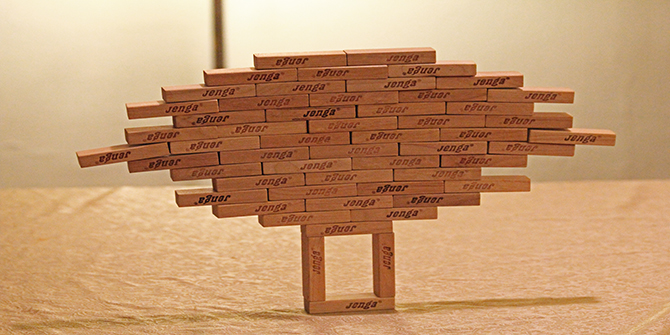

Featured image credit: cisc1970 BY-NC

And the game may just have changed

https://stv.tv/news/politics/1382623-stv-poll-half-of-scots-would-vote-for-independence/

There is of course the Claim of Right, which seems to be ignored here, and the option to end the union in the same way it began: :

http://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2017/02/18/it-is-now-time-for-scotlands-mps-to-declare-scotlands-independence/

The people of Scotland have been repeatedly told since the 2014 referendum that they must “respect the result”. Yet the actions of the Unionists (Labour and the LibDems as well as the Tory UKGov) have been anything but respectful of the result. Viz. “EVEL” , the Smith Commission’s least-common-denominator response, the reaction to the EU referendum result in Scotland, etc., very little account has been taken of the legitimate wishes of the substantial minority.

Democracy has to be rather more than mere majoritarian triumphalism as manifested in referenda. It is the clash of these various triumphalisms that has left Scotland (which for substantive historical reasons is not merely another region of England, as some posters here seem to implicitly believe) in an intolerable constitutional position that can only be resolved, one way or the other, by a new independence referendum.

It is as inevitable as the influx of the tide.

Yes. Yes it is a democratic outrage.

The trick is in getting enough decent people in the UK to recognise the fact, stand up and say ‘enough’.

Unlikely to happen though given the current climate. Nor would anyone listen to an opposing view UK wide regardless. The voice too small you see and that’s not the narrative of orthodoxy. Not from central government, nor the media. A narrative I believe which is way beyond control at this point.

There will be a hard Brexit. There will be a constitutional crisis with Northern Ireland and Scotland (not of their making). There will, I believe, be another independence referendum as a result.

Whether the UK makes it out of Brexit as a state entity or not, I very much doubt it’s society will ever be the same again.

You seem to miss the crux of the issue of sovereignty here.

“Parliamentary sovereignty” is a peculiarly English concept that does not exist in Scots law.

In Scotland, it is “the people” who are sovereign.

Scotland remains part of the Union because those who wished it so won the Scottish referendum and the SNP lost it. Where’s the “democratic outrage” in that? The UK will leave the European Union because the quitters won that referendum and the Westminster Government respects the will of the British people. No outrage there. Scotland’s devolved administration was created by the Westminster Parliament and is kept afloat by British trade and subsidies. Lucky Scotland.

In the 2014 referendum one argument for staying in the Union was that Scotland might not be able join the EU as an independent nation, and, by implication, staying in the UK was the best way of staying in the EU. The latter is now clearly not the case. Given that, while the EU referendum was a UK-wide vote, it showed that Scotland had a different view from England and Wales, would it be a democratic outrage to have a Scottish EU/UK vote?

The unionist argument that the 2014 vote determines the issue settled.

a) people are increasingly aware of the extent to which they were misled (Vow / remain in Europe / etc)

b) a material change has taken place – Brexit

I wonder why Westminster fights so hard to hold Scotland in it’s grasp. It could be that the lie and continue to lie about our potential. The too wee, to poor and too stupid rant sounds hollow when I look at the de-population and asset stripping over the last 300 years.

Scotland has subsidised Westminster. It is on record until the1940’s listed transfers of up to 50 percent of our wealth “in support of the Empire”. It is strange that this measurement ceased around the time of the first SNP MPs election.

If there isn’t a Scottish constitutional vote in connection with Brexit, I find it hard to predict there being another opportunity for Scotland to join the EU/EEA for a generation anyway. The only reason for a referendum within the Article 50 period is Brexit, and the choice must be “Scotland in the EU/EEA or Scotland in the UK”.

Even if the polls are not favourable for Scotland to leave the UK and remain with the EU/EEA, I would like to see a vote in time for Scotland, should it become independent of Westminster, to become a member of the EEA/EU the day that the rest of the UK leaves.

Your statement that “foreign policy is invariably a matter reserved for central government, even in federal systems” is factually incorrect: see Belgium.

True. But this reflects the fact that Belgium is essentially a binational (or arguably ‘trinational’) state, and one which is barely hanging together as it is – didn’t they have no government for about a year recently because they couldn’t agree on one?

Well the latest polls seem to show, despite what sturgeon claims more people want to stay in the UK than go independent, Scotland and England are not and never will be equal partners because Scotland despite its land mass has a small population, less than that of London alone. This would seem to indicate the Scots fear being totally independent than are upset that their one man one vote response to the referendum was on the losing side.

“Well the latest polls seem to show, despite what sturgeon claims more people want to stay in the UK than go independent”. Agreed. In fact, I said that in the article you’re commenting on 🙂 but that can change, the pro Indy vote is growing. Perhaps what they really want is to remain in BOTH the EU and the UK. Scotland was unique in the solidity of its Remain vote (whereas in Northern Ireland not only was the Remain victory smaller, but there were sharp regional differences – west of the Bann, Remain, east Leaved – an obvious partial overlap with the nationalist/unionist divide.

Correction. 58 out of 59 MPs voted against Brexit. The only MP to vote in favour was David Mundell, the lone Tory, who only held his seat narrowly by 800 votes at the last General Election.

Good point – I was counting by party (56 SNP + 1 Lib Dem), not individual MPs. Even that was a bit flawed as not all Lib Dem MPs voted against triggering Art 50 (two abstained).

There is nothing outrageous or intolerable here. Until such time as Scotland is independent, it is the sovereignty of the British people that is the issue. Scottish people voted against independence. You’ve stated that: ‘The Scottish Parliament is not a sovereign body’, but then argued as if it is.

You should ask yourself this question: if the UK had voted to remain, but one of the devolved nations of Wales or Scotland had voted to leave, would you regard it as intolerable that they had to remain?

“it is the sovereignty of the British people that is the issue”. No, it is the Westminster Parliament, not the people, which is sovereign – that’s what the Supreme Court case was all about. Would I regard it as intolerable if one of the devolved nations had voted to leave but the UK had voted to Remain? That would rather depend on whether or not there had been a recent referendum on independence in which EU membership was a prominent issue. In any case, the choice Brexit or independence represents only the extreme poles of the issue – there are potential positions within that range.

It’s hardly a “democratic outrage”, is it? If the people of Scotland didn’t get a vote on EU membership that would be an outrage, but their votes carried the same weight as everybody in the UK. This is a UK that they recently voted to remain part of.

This is a UK that they recently voted to remain a part of on the premise that doing so was the only way to ensure continued membership of the EU. That premise was false, the situation is materially altered.

Here’s an analogy. A marriage is getting pretty rocky and the wife is seriously thinking about leaving. So the husband promises her lots of little favours, doing his share of the washing-up and suchlike, but also points out that he owns the car and if she leaves she’ll no longer get to use it. Well the favours only last a week but things still rub along somehow out of habit … then the car is reposessed! So what is left to stop her leaving now?

Brexit has exposed the reality. As you point out, the first question now is whether a majority of Scots are happy to leave it that way. The next is whether London abolishes the Scottish Parliament and resumes direct rule.

To be Diceyan on it, it is legally possible for Westminster to abolish Holyrood – but it is a POLITICAL impossibility.

I hope you’re right (political impossibility). There are very strong hints coming from the Tories, that they intend something that would be very controversial in Scotland.

I agree, Margaret. These changes to the Secretary of State for Scotland’s office and the large increase in both funding and personnel enjoyed by that office suggests something is in the wind. I, personally, do not believe for a nanosecond that Westminster will agree to another indyref. Even if it did, I believe it is a cruel deception to let the people believe there is any hope. of winning it because the numbers against will more than in 2014. The only hope we have is to challenge the constitutional settlement itself as part of the defence of the Continuity Bill in the UKSC. I think that this is their Achilles’ Heel because a proper delve into the Treaties and Acts of Union show quite conclusively that a new British parliament was born in 1707 and the English principle of sovereignty of parliament is a scam. Not only that, but ample proof exists to show that Scotland was never subsumed either but continued as a nation, if a politically stateless one. If Westminster and Whitehall try to deny this, they will be heading for a constitutional make or break. We do not have long to get this strand of the defence off the ground, and we should be petitioning the UN, too, right now.

I’m not sure Westminster will seek a direct confrontation with the Scottish Parliament yet, to abolish it like the GLC. However, they will I think try to “freeze” it via the “Great Repeal Bill”, agressively withhold “repatriated powers” from the EU as reserved matters for Westminster, and then by-pass it to the local council level for any new legislation, thus gradually emasculating it. The questions which remain are whether the Scottish Parliament can claim to be the voice of Scots’ sovereignty, whether the Supreme Court may legitimately be the court of appeal for Scots Law, and whether a new independence referendum could be held without reference to Westminster, perhaps in a Council of Europe or UN framework. May’s calls for “collective responsibility” should be recognised for the renewed attempt at colonisation which they are, and the consequence will be constitutional and institutional political tussling.