Kieran Wright argues that changes in Scottish public opinion since the introduction of devolution have neutralised certain features of the Scottish Conservative Party that used to be a significant electoral liability.

Kieran Wright argues that changes in Scottish public opinion since the introduction of devolution have neutralised certain features of the Scottish Conservative Party that used to be a significant electoral liability.

In marked contrast to the party’s anaemic performance in the rest of Great Britain, the Conservative Party in Scotland enjoyed its best night in decades in the 2017 general election. It won more Westminster seats than it had done since 1983, and won its largest share of the Scottish vote since it ousted Labour from power in 1979. For most of the past two decades, the party failed to win more than a single Westminster seat, and struggled to make an impact at Holyrood.

What caused this dramatic revival in the party’s fortunes in Scotland? It is commonly assumed that the reasons for the collapse of the Conservatives in Scotland that culminated in the party ceasing to exist at parliamentary level at the 1997 general election centred around a rejection of Thatcherism and the Poll Tax in particular. In reality, the party’s decline began long before the ascent of Margaret Thatcher.

In 1964, the Conservatives began to contest Scottish elections without the use of the formal “Unionist” description in response to the perceived declining relevance of taking a distinctively unionist stance. The Conservative’s problem was that conservatism without unionism had much less appeal; a problem exacerbated by the fact that the brand of conservatism it was putting forward moved increasingly towards incorporating a form of economic liberalism that had limited support in Scotland. The party went on to lose seats in six out of the nine Westminster elections that took place after 1960, culminating in the wipeout of 1997. Its decline would only begin to reverse when its unionism, once again, became a relevant distinguishing feature – and indeed, an asset.

Sometime Labour Secretary of State for Defence George Robertson infamously predicted that devolution would “kill nationalism stone dead”. In fact, devolution was ultimately to provide the catalyst for the rise of Scottish nationalism, with the Scottish National Party coming to power in the Scottish Parliament and support for independence reaching unprecedented levels. Paradoxically, this rise of nationalism was to provide an opening for the most unionist party in Scotland.

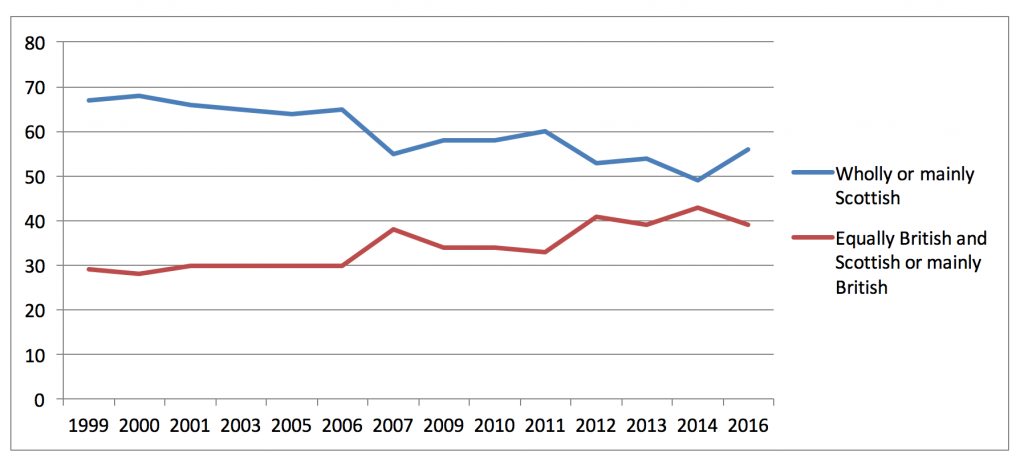

Figure 1: Which best describes you, on scale from ‘Scottish not British’ to ‘British not Scottish’?

The above chart is compiled using data from the ‘Moreno’ national identity question in the regular Scottish Social Attitudes Survey. It asks respondents to state whether they feel wholly or mainly Scottish, wholly or mainly British or equally Scottish and British. It shows a trend away from respondents citing a wholly or mainly Scottish identity and towards more people saying they are equally Scottish and British or wholly or mainly British.

The above chart is compiled using data from the ‘Moreno’ national identity question in the regular Scottish Social Attitudes Survey. It asks respondents to state whether they feel wholly or mainly Scottish, wholly or mainly British or equally Scottish and British. It shows a trend away from respondents citing a wholly or mainly Scottish identity and towards more people saying they are equally Scottish and British or wholly or mainly British.

The trend is partially reversed in the most recent survey conducted in 2016 in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum. It remains to be seen whether this presages a new trend, or is one-off reaction to the surprise Brexit vote. Whatever is the case, the fact remains that the trend since devolution is towards more respondents citing a British aspect to their identity that is at least as important as any Scottish component.

Devolution has clearly provided a context in which Scottish nationalism has achieved unprecedented levels of support. However, while a significant section of the Scottish electorate are clearly attracted to nationalism, a significant portion also seem to be repelled by it. The rise of the SNP has been accompanied by a rise in the number of Scottish voters citing Britishness as a significant aspect of their identity.

For the Scottish Conservatives, this is hugely significant. It creates a situation in which the perceived Britishness of a staunchly unionist party is no longer the electoral liability it was back at the turn of the century when two-thirds of the Scottish electorate saw themselves as predominantly not British. Indeed, it proved to be as strong point when appealing for the votes of those opposed to the idea of a second referendum on Scottish independence, something that formed the cornerstone of the party’s 2017 campaign in Scotland.

In the years since the introduction of devolution, the Scottish electorate has also become more eurosceptic. At the turn of the century, Scottish Social Attitudes found just 11% of Scottish voters wanting to see their country leave the European Union, while only 27% wanted to see the EU’s powers reduced. In the most recent survey, 25% support Brexit (an even larger 38% actually voted to leave the EU in the 2016 referendum), while the number wanting the EU to have fewer powers has leapt to 42%. This is of obvious benefit to the Scottish Conservatives, reducing the extent to which their euroscepticism estranges them from significant sections of the Scottish electorate, and addressing the more general impression that their vision of the kind of country Scotland should be is widely different to that shared by most Scottish voters.

Of course, there are other factors contributing to the much improved performance by the Scottish Conservatives in 2017. Their leader, Ruth Davidson, is undoubtedly an electoral asset. In every Yougov survey on the Scottish party leaders conducted this year Davidson has enjoyed a better net favourability rating than First Minister Nicola Sturgeon. But it is unlikely that the party could have reaped the full benefits of having a widely respected leader had there not also been shifts in Scottish public opinion that make in particular the party’s British Unionism, but also its euroscepticism, much less electorally toxic than used to be the case.

_____

Kieran Wright is Assistant Lecturer and PhD candidate at the School of Politics and International Relations, University of Kent.

Kieran Wright is Assistant Lecturer and PhD candidate at the School of Politics and International Relations, University of Kent.

It remains to be seen how much of a revival of Tory fortunes the 2017 election was. The unionist parties succeeded in turning the election into a vote against a second independence referendum thus allowing much of the unionist vote to coalesce around the Tories, notably at the expense of the Liberal Democrats who were trying to occupy the same electoral space.

However, the focus on unionism has partly concealed the other issue in the election, social justice. As you rightly point out, the Tory vote in Scotland was diminishing before Thatcher because of the Tories’ economic liberalism but it came to a head in 1997 when the party was left with no seats in Scotland. Following the 2017 election the actions of the London government have detracted from the Scottish Conservatives’ election success by re-emphasising the gap between Tory economic and social policy and Scottish opinion. Scottish Labour’s revival in the election was after all fuelled by a ‘Corbyn bounce’ of support for more radical social democratic policies and Scottish public opinion still rejects Brexit by a 2:1 margin. The new cohort of Tory MPs has found itself ignored by the Westminster leadership and left silent in opposing policies which are widely perceived to harm the Scottish economy.

In short, the Conservatives electoral success has not really changed much. There was always going to be a rebalancing of party seat shares as the unpopular effects of the ‘Better Together’ campaign on the 2015 election wore off. A Labour revival and a further shift back to the SNP fuelled by Westminster’s incompetence could easily see the Scottish Conservatives back where they were in 2017 in comparatively short order.

Some of this is interesting, but it’s a shame that you equate support for Scottish independence with nationalism, but support for unionism as a rejection of nationalism. Supporters of Scottish independence are often Scottish nationalists, but often aren’t. Similarly, supporters of unionism are often British nationalists, but often aren’t.

I’d go so far as to say that the anti-independence movement is more nationalistic than the pro-independence movement, in many ways. It’s also worth noting that Scottish nationalists typically endorse some sort of civic nationalism, whereas British nationalism is much more frequently of the blood-and-soil variety. Whether you agree with that or not, it’s extremely misleading to identify support for independence with nationalism and rejection of it as a rejection of nationalism.

It’s a rhetorical strategy employed by Teresa May and a number of other unionists who always refer to the SNP as ‘the nationalists’, despite every major political party in the UK bursting with British nationalists of one kind or another.