Tania Burchardt writes that the National Insurance increases to fund a lifetime cap on social care costs leave untouched two much bigger problems: the gap between need and services, and the inequalities in the experience of (and access to) care.

Tania Burchardt writes that the National Insurance increases to fund a lifetime cap on social care costs leave untouched two much bigger problems: the gap between need and services, and the inequalities in the experience of (and access to) care.

The UK government recently announced a package of measures to reform adult social care in England. By capping lifetime care costs and making the means-test somewhat less mean, it promises a re-balancing of financial liability between families and the state that was agreed but never implemented in 2014. In so doing, it will begin to address one of the sources of inequity in the present system, namely the very high costs faced by people unlucky enough to have substantial and prolonged care needs.

But will this, ‘fix the crisis in social care once and for all’, as Boris Johnson pledged in his first speech as Prime Minister in July 2019? No. It leaves largely untouched two much bigger problems: unmet need for care, and inequalities in access to and experiences of care. Chronic under-funding of the sector as a whole has produced a chasm of unmet need and resulted in high and rising burdens on unpaid carers, whilst underlying inequalities between people in deprived and non-deprived areas, and between different ethnic groups have been neither recognised nor addressed.

Pre-pandemic, local authorities in England with responsibilities for adult social care had suffered a decade of austerity. Spending on adult social care remained 4.3% lower in real terms in 2018/19 than it had been in 2009/10, and this was in the context of a 17% growth over this period in the size of the population aged 80+. More resources were beginning to be directed towards social care through pooled budgets with the NHS, but these were not sufficient to offset population pressures nor the accumulation of under-funding over the decade.

In response to the decade-long squeeze on revenue, local authorities have concentrated resources on the people with the highest level of need and withdrawn support – or declined to offer it in the first place – to others. According to our best estimate (direct comparisons are tricky because of a break in the published statistics), the number of people receiving support in their own homes or in the community nearly halved between 2009/10 and 2018/19. As a result, by 2018, one quarter of all adults aged 65 or over had some unmet need for help with an activity of daily living (such as washing or dressing) – that’s roughly 2.4 million people. And the most exposed to having their needs unmet are the oldest of the old: one in three men aged 80+, and nearly one half of women in that age group. We don’t yet have post-pandemic figures, but the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services released a survey suggesting that 300,000 people were awaiting assessments in August, and that this number had risen by one quarter in the last three months. Given the interruptions in services due to COVID-19, and the new workforce pressures from Brexit, it would not be surprising to find that levels of unmet have risen yet further.

A previous Conservative minister expressed the view that families should do more to look after their elderly relatives. But unpaid carers – mostly spouses and daughters, also sons and others – already provide an estimated £57bn- to £100bn-worth of care per year, and a higher proportion of the over-50s in the UK are unpaid carers compared to most other OECD countries. Moreover, caring is becoming more intense; one in three carers were providing 35 hours of care a week or more in 2018/19, a proportion that was closer to one in four only eight years earlier. Longer hours of care make paid employment difficult or impossible, and are associated with greater mental and physical strain.

The government announced in September 2021 an additional £1.8bn per year for three years for social care; according to the accompanying statement, this has been calculated to be enough to cover the costs of the charging reforms and knock-on administrative costs for local authorities. Whether it will in practice be sufficient remains to be seen. But in any case, it is not intended to, and will not, expand the availability of care, nor will it widen the definition of care needs eligible for publicly funded support. Meanwhile, unpaid carers must, once again, be content with warm words: the government will, ‘take steps to ensure that the 5.4m unpaid carers have the support, advice and respite they need’ – but there is no new funding attached to this commitment.

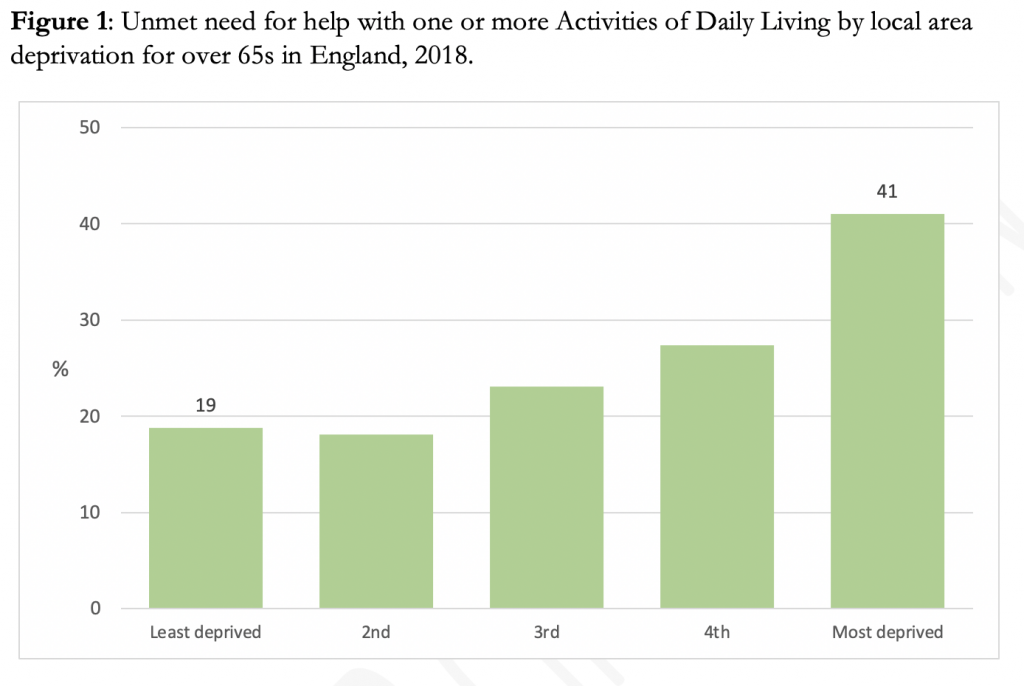

We are, however, promised a further White Paper on adult social care ‘later this year’. This could provide the opportunity to recognise and address the second major challenge: inequalities. Need, and unmet need, are not equally distributed across England. Unmet need is concentrated in areas with higher levels of multiple deprivation; in fact, for the over-65s, the risk of unmet need for help with one or more activities of daily living is more than twice as high if they live in a local area which is among the fifth most deprived, compared to the risk if they live in one of the least deprived areas, as shown in Figure 1. The formula for allocating resources to local authorities with more deprived populations should reflect not only their economic and health inequalities but also these additional care inequalities. Likewise, the strategies for further integration of health and social care services must recognise the ‘triple whammy’ of economic, health and care inequalities, and the relationship between them.

Source: Author’s calculations based on published tables in Health Survey for England 2018. Age-standardised. Local area deprivation is measured by quintile groups of the Index of Multiple Deprivation.

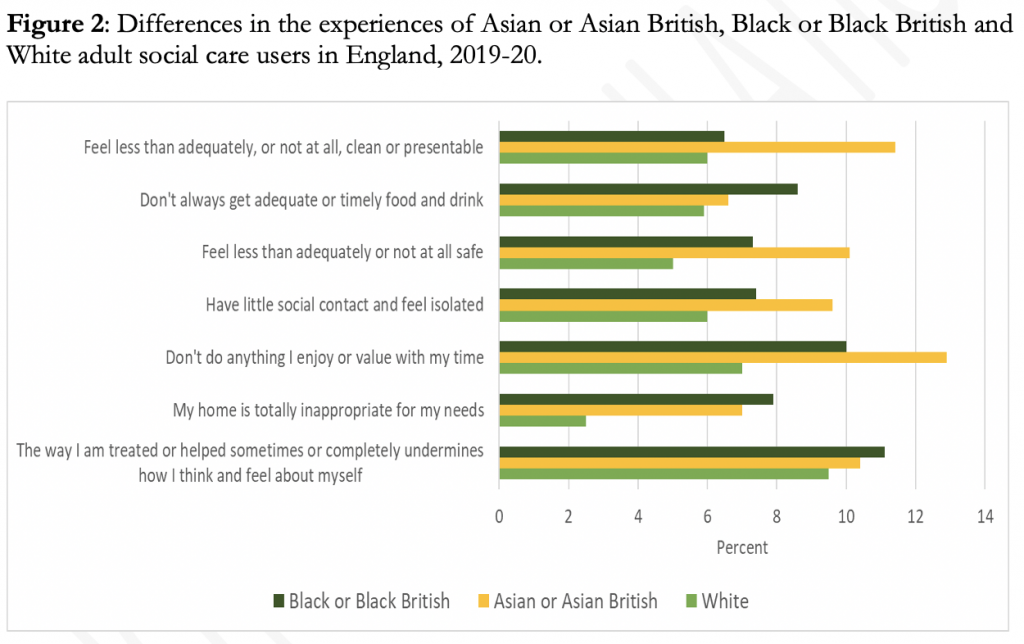

It is also troubling to note that among those who are receiving services (whether paid for publicly or privately), those from Black/Black British and Asian/Asian British ethnic backgrounds report worse experiences of care on average than users from a White background (see Figure 2).

Source: Social Care Users Survey 2019-20. Author’s calculations based on Annex tables.

Source: Social Care Users Survey 2019-20. Author’s calculations based on Annex tables.

For example, 11.% of Black/Black British and 10% of Asian/Asian British care users feel that, ‘The way I’m helped and treated sometimes, or completely, undermines the way I think and feel about myself”. This compares to 9.5% of White care users. The fact that around one in ten care users overall are reporting this experience is an urgent matter of concern in itself, but the differences between ethnic groups is also worrying.

The recent announcement, whilst a welcome (belated) step towards taking collective responsibility for the risk of very high care costs, will not make the crisis in social care go away. It addresses neither the yawning gap between need and services (including for carers), nor the worse access to and experiences of care for people in deprived areas and for ethnic minorities. The government has made rhetorical commitments to ‘levelling up’ and to reducing ‘ethnic disparities’. A funded strategy to tackle unmet need and address inequalities in the experience of care in the forthcoming White Paper on adult social care would be a good way to demonstrate that it is serious about turning the rhetoric into reality.

____________________

Note: the above draws on the Social Policies and Distributional Outcomes in a Changing Britain report, funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

Tania Burchardt is Associate Director of the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, Deputy Director of STICERD, and an Associate Professor in the Department of Social Policy at the LSE.

Tania Burchardt is Associate Director of the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, Deputy Director of STICERD, and an Associate Professor in the Department of Social Policy at the LSE.

Photo by Steven HWG on Unsplash.