Recent research based on data looking at British attitudes to welfare suggests policy-makers may be out of step with public opinion in this area. Kate Summers, Ben Baumberg Geiger, Robert de Vries, and Tom O’Grady explain what has happened to public attitudes to welfare over the past 15 years, and why.

As we move towards a general election sometime in 2024, neither of the main parties appears particularly keen to talk about welfare. Keir Starmer has, from his permanent defensive crouch, refused to say that Labour would reverse the two-child limit; while the Tories have quietly hinted that many benefits may not be uprated in line with inflation (ie, that they will face a substantial real terms cut). However, recent research we have conducted using the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey shows that there is also increasing political space for more pro-welfare policies as anti-welfare attitudes have fallen sharply since 2010.

Benefit claimants seen as more deserving than ever

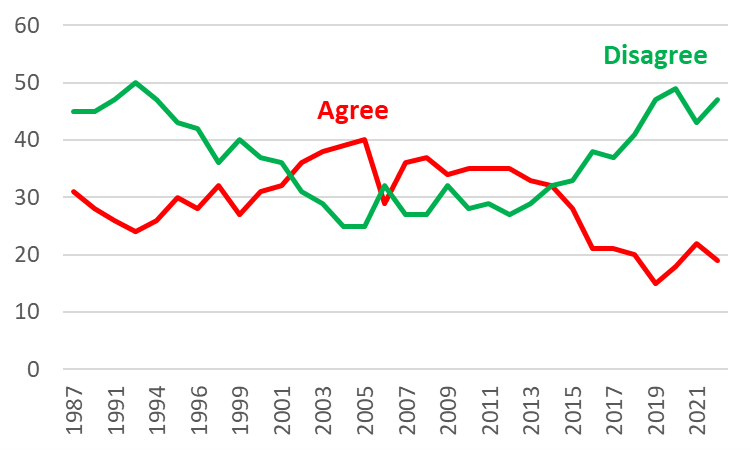

To get at how deserving welfare claimants are perceived to be, the British Social Attitudes survey has asked the public each year since 1986 whether they agree or disagree that:

“Many people who get social security don’t really deserve any help”

Looking at figure 1, we can see that agreement with this statement rose through the late 1980s and 1990s, reaching a peak in 2005, when 40 per cent of people thought that many claimants did not really deserve help. Since the 2010s, however, we have seen support for this view steadily decline. Now only 19 per cent of the British public agree that many claimants are undeserving (it is important to note that this change happened before, not during, the COVID-19 pandemic).

Figure 1. Agreement that “many people who get social security don’t really deserve any help” 1987-2022

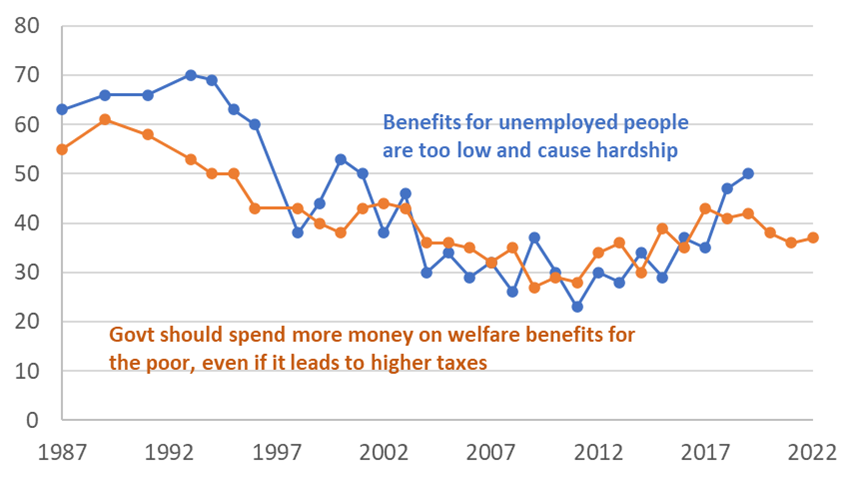

Over the same period, we have also seen a resurgence – albeit more modest – in support for welfare spending. Figure 2 below shows agreement and disagreement with the following statement:

“The government should spend more money on welfare benefits for the poor, even if it leads to higher taxes.”

As well as answers to this question (only available to 2019):

“Opinions differ about the level of benefits for unemployed people. Which of these two statements comes closest to your own view?

… benefits for unemployed people are too low and cause hardship,

… or, benefits for unemployed people are too high and discourage them from finding jobs?”

As the chart shows, there has been a steady rise in support since 2010 for higher spending on welfare benefits, and in the belief that unemployment benefits are too low. However, attitudes remain less generous than they were in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Figure 2. Support for welfare spending, 1987-2022

Why have anti-welfare attitudes fallen?

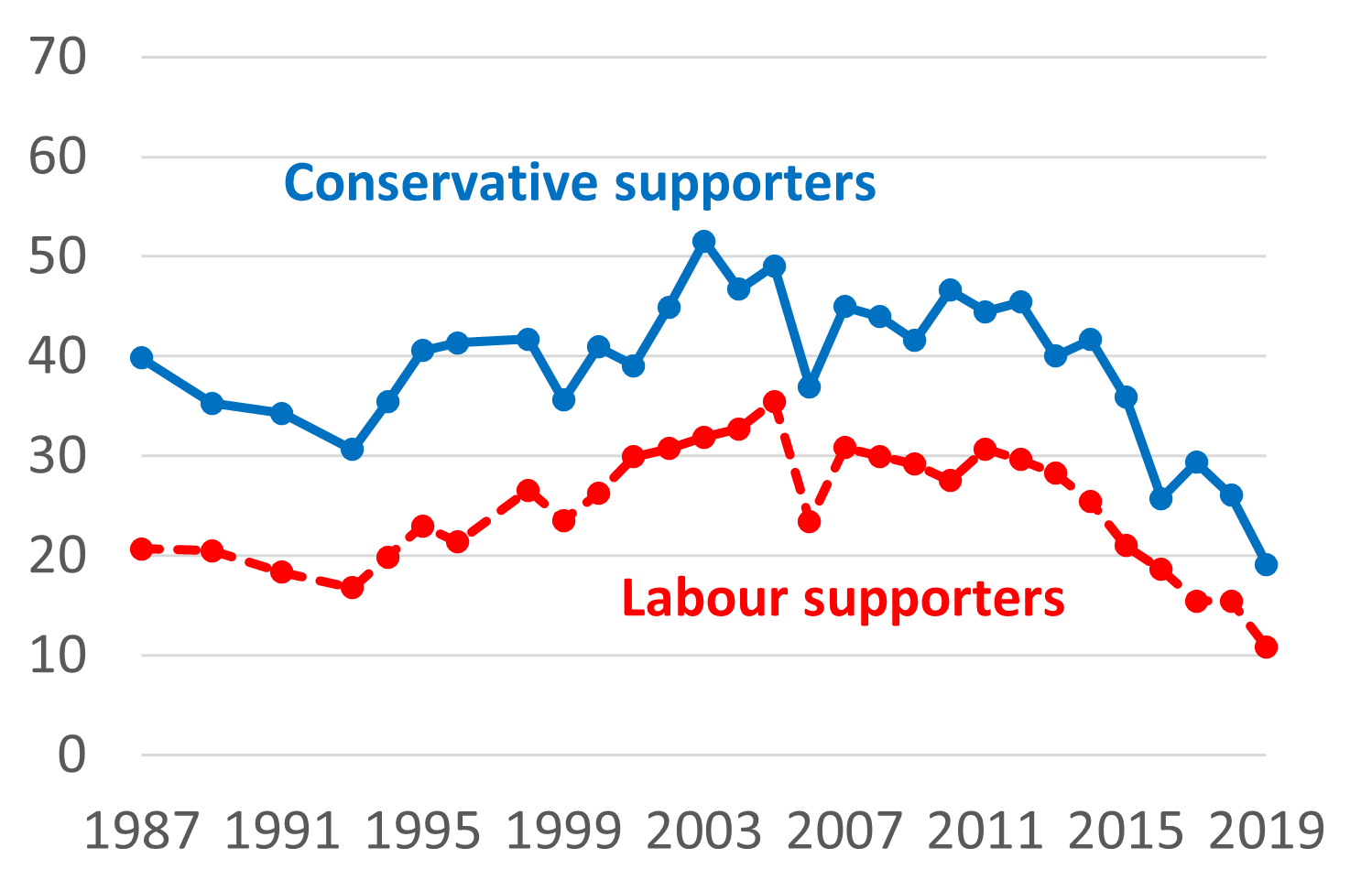

We know from previous research that the Labour Party’s harsher line on welfare through the 1990s and 2000s led to a hardening in attitudes among Labour Party supporters. However, if we look at changes in public attitudes since the 2010s, the picture is less clear.

The decade from 2010 onwards saw a clearer divergence between the Conservatives and Labour on welfare policy. The Conservatives took aim at “welfare scroungers” and enacted welfare cuts and freezes as part of the austerity agenda. Meanwhile Labour, particularly following the election of Jeremy Corbyn, expressed far greater sympathy for welfare claimants. However, we do not see this divergence reflected in the attitudes of party supporters. Instead, we see attitudes among members of both parties becoming more generous largely in parallel, as shown in Figure 3 below. So what explains this universal softening of attitudes?

Figure 3. Agreement that “many people who get social security don’t really deserve any help”, by political party, 1987-2019

Our conclusion, based on our analysis of BSA data, is that there is no clear, single driver of the increasing generosity of welfare attitudes observed over the last decade. Instead, a number of factors intertwined to create the necessary conditions. Crucial is the changing nature of welfare policy itself.

During the 2010s, the Conservatives and their allies in the press hammered benefit claimants as scroungers while pushing through a series of high-profile reforms which made benefits less generous and harder to get. The objective worsening of conditions on welfare made it harder and harder for the public to believe that claimants were mostly undeserving scroungers growing rich on government largesse. Media stories about claimants with massive houses and expensive hobbies became less prevalent as they fell even further out of step with reality – even the Daily Mail became more sympathetic to welfare over this period. Political rhetoric largely followed, softening to the extent that, when the pandemic erupted, Conservative MPs could talk of their pride in Britain’s social security system without getting whiplash.

This is not a simple, linear story – objective conditions changed so attitudes changed – partly because people’s perceptions of what the objective conditions are is strongly influenced and contextualised by the media (as one of us has found for judgements of disability). Instead, all of these factors will have fed from and into each other to steadily erode anti-welfare sentiment.

So what now?

Public attitudes are currently much more pro-welfare than they have been for a very long time – and pro-welfare policies are therefore likely to land much more positively than in the early 2010s. That said, while more people want rises in welfare spending than in 2010, this is not on the scale of the 1980s and early 1990s. And even now, the British public have a hair-trigger tendency to sort the deserving from the undeserving.

Public attitudes to welfare are always ambivalent; even after World War Two when the Beveridge Report was being implemented, there was no “golden age” of overwhelming public support. Radical welfare reforms often require political courage, working to persuade an uncertain public who will be swayed by the arguments that reformers make. But this is a moment in which there are more political risks in anti-welfare policies – and more potential political opportunities for pro-welfare policies.

This blog post draws on the chapter “The rise and fall of anti-welfare attitudes across four decades: politics, pensioners and poverty”, part of the British Social Attitudes 40th Anniversary Edition.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by Timon Studler via Unsplash.