Concerns about the health burden of obesity have prompted governments across the world to introduce sugar taxes. In March 2016, the UK Government announced a national Soft Drinks Industry Levy which was enacted in April 2018. Alex Dickson, Markus Gehrsitz, and Jonathan Kemp assess the effects of the levy by analysing data on the universe of soft drink sales in UK grocery and convenience stores. They find that product reformulation was the key driver behind large levy-induced calorie reductions.

Concerns about the health burden of obesity have prompted governments across the world to introduce sugar taxes. In March 2016, the UK Government announced a national Soft Drinks Industry Levy which was enacted in April 2018. Alex Dickson, Markus Gehrsitz, and Jonathan Kemp assess the effects of the levy by analysing data on the universe of soft drink sales in UK grocery and convenience stores. They find that product reformulation was the key driver behind large levy-induced calorie reductions.

When the National Food Strategy was unveiled on 15 July 2021, one recommendation in the report drew the attention of policymakers and general public alike: Henry Dimbleby, the prominent business man and restaurateur who was commissioned with drafting the government-commissioned report, advocated the introduction of a £3 tax per kilo of sugar in processed foods. The report dubbed this a ‘reformulation tax’ and pointed to the UK Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) – which has been in place since 2018 – as a model that both induced manufacturers to reduce the sugar levels in their products and raised tax revenue that could, in turn, be used to subsidise fruit and vegetables.

Our recent study of the SDIL suggests that a comparison of the newly proposed sugar tax on processed food and the 2018 sugar levy may be flawed. We find that the sugar levy indeed delivered a large, 6,500 calorie reduction per UK resident per year, but did so because of a more nuanced design that created a clearer incentive for soft drinks reformulation than a flat £3/kilo sugar tax would provide.

The SDIL, when it was announced in March 2016, represented a significant potential increase in the ‘cost of goods’ for manufacturers of ‘regular’ sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs). The majority of regular drinks contained a sugar content some 25% above the highest tier of the SDIL which was set at eight grams of sugar per 100ml, triggering a levy rate of 24p per litre sold. The addition of VAT following a full pass through of the SDIL to consumers via retailers sees an additional 4.8p of VAT added.

This 24p + 4.8p is of a similar magnitude to the tax proposed by the National Food Strategy. One goal of the SDIL was to substantially raise retail prices on regular SSB’s and thus trigger a demand response by prompting consumers to reduce their consumption levels whilst raising tax for the UK Treasury. However, the main aspect that made the SDIL a success – and arguably one that is missing from the National Food Strategy – was a clear provision designed to trigger a significant supply response: brands that reduced their sugar content below 5g/100ml would not be levied. Put more bluntly, it gave a clear choice to the brand owner: if you halve the sugar content in your regular drinks by 6 April 2018 you will avoid this levy.

We went to the data to assess the effectiveness of the SDIL in general and the levy exemption in particular.

Reformulation incentives work – all but a few brands cut their sugar content

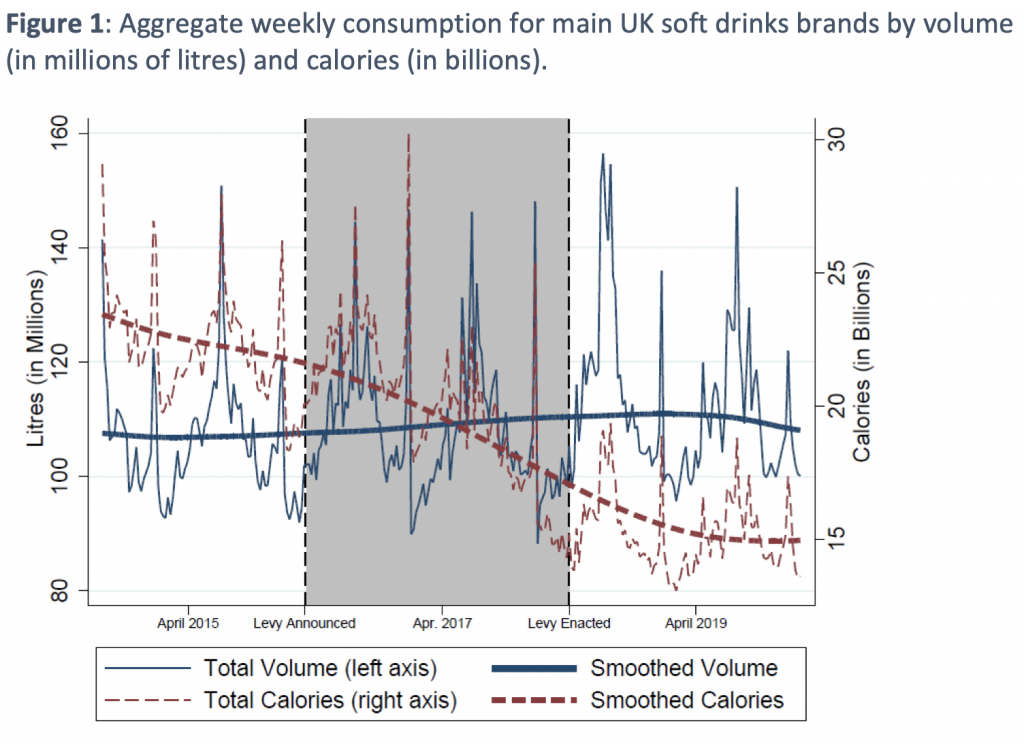

Our data analysis shows that the levy led to massive reductions in the calorie intake and that, remarkably, most of these reductions were realised before the levy even went into effect (see Figure 1). That is because many manufacturers used the two-year gap between levy announcement in March 2016 and enactment in 2018 to change the recipes of their beverages. By substituting artificial sweeteners for some of the sugar, they cut their sugar content below the 5g/100ml threshold, thus avoiding the levy. Among the 100 main brands and brand variants, which account for 73% of consumer spent in UK mainstream retailers, product reformulation was responsible for a reduction in calorie intake of about five billion calories per week. Consumers seem to barely have noticed the product reformulations as prices and volume sales held steady both before and after the enactment of the levy.

Only the strongest brands passed on the levy to the consumer – and paid a price for it

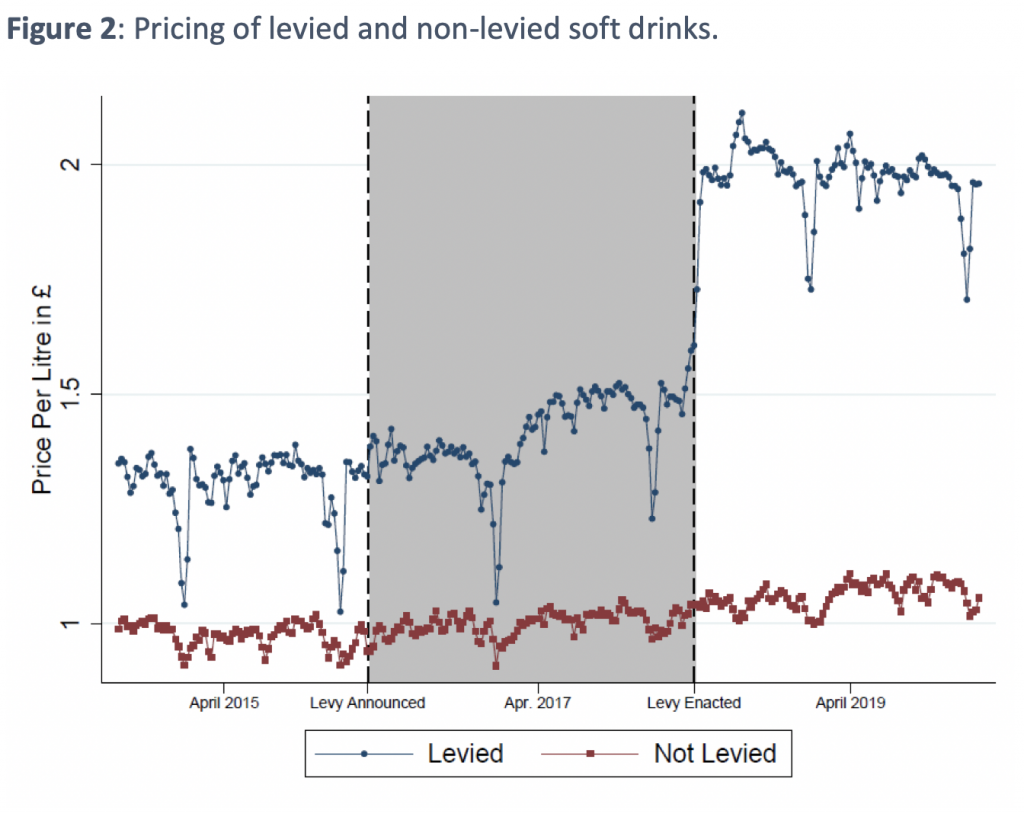

But not everyone changed their recipe. In particular, in the cola and energy drink segments of the market, full-sugar variants continued to feature prominently at the time the levy was implemented in April 2018. Figure 2 shows that as the levy was passed on to consumers, retail prices increased significantly. In particular for colas, the price paid by consumers increased by more than the nominal tax which was over-shifted.

The consumer response to this substantial change in retail pricing followed swiftly and took the form of about an 18% reduction in volume sales of levied brands. The sales response was most pronounced for large ‘take-home’ containers of colas whereas, ‘on-the-go’ purchases of energy drinks actually continued to grow volumes throughout this period. At the same time, sales of zero sugar/diet versions increased supporting the continued growth path of the overall soft drink market volumes. In total, levy-induced price increases and the subsequent substitution behaviour took a further one billion calories per week out of UK consumers’ diet.

Supply-side response trumps demand-side response

Our study concludes that the UK SDIL holds important lessons that are all the more relevant in light of the suggestions made in the National Food Strategy Independent Review.

First, while the demand-response to higher prices was non-negligible, it was dwarfed by calorie reductions by way of manufacturers’ decision to cut the sugar content in their beverages. More than 80% of overall levy-induced calorie reductions were due to reformulation. Put differently, a close look at the data revealed that most of the commonly used models of consumer behaviour overestimate consumers’ price sensitivity and under-appreciate the role of suppliers’ responses.

Second, key to the success of the SDIL were strong incentives for product reformulation. Its tiered nature with a clearly defined and achievable target sugar level below which the levy could entirely be avoided, provided a clear financial reward for sugar content reductions.

Third, the two years between announcement and implementation gave manufacturers sufficient time to launch reformulated products.

Fourth, the soft drinks industry was already moving in the direction of lower calorie drinks, and had the skill and supplier relationships to respond to these incentives by providing lower calorie versions of their products that still satisfied consumer tastes. In other words, the SDIL acted as an accelerator. Sugar intake from soft drinks had been falling long before the levy was announced (see Figure 1), mainly because of the way consumer centric brands owners responded to both changing consumer preferences and retailer sentiment.

Last but not least, our study confirms the old economics adage that ‘there is no such thing as a free lunch’. Just as the National Food Strategy proposes to use tax revenue to subsidise healthy foods, the UK Treasury had estimated the SDIL to raise £520 million per year, all of which was earmarked to help tackle the obesity crisis in schools by way of providing healthier meals and support for school sports. In 2019/20, levy revenue amounted to only £336 million. This illustrates the trade-off between calorie reductions, on the one hand, and raising funds by way of a sugar tax, on the other hand. A tax that induces large sugar reductions will likely raise little revenue, and vice versa.

______________

Alex Dickson is Reader in Economics at the University of Strathclyde.

Alex Dickson is Reader in Economics at the University of Strathclyde.

Markus Gehrsitz is a Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of Strathclyde.

Markus Gehrsitz is a Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of Strathclyde.

Jonathan Kemp is the Commercial Director of AG Barr and a part time PhD student at the University of Strathclyde.

Jonathan Kemp is the Commercial Director of AG Barr and a part time PhD student at the University of Strathclyde.