Sport in Northern Ireland has long been more than just a leisure activity, but a symbol of religious, cultural and, often, political allegiances in the province’s divided society. But, in a recent research project, David Mitchell, Ian Somerville and Owen Hargie suggest that some of the politicisation of sport in the region may be weakening.

In the wake of Brexit and US election, it is easy to forget that anything else happened in 2016. In Ireland, the year was long-anticipated as the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising and the Battle of the Somme, totemic historical moments for Irish nationalists and Ulster unionists respectively. Meanwhile, in June 2016, the football teams of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland appeared in the finals of the European Championships in France.

The coincidence of the centenaries, and the improbable soccer success, drew little comment. Yet the resonances are interesting. The very existence of two international football teams on the island of Ireland can arguably be traced to the 1916 Rising, which was part of a series of seismic events which shaped modern, partitioned, Ireland. Moreover, both historical commemorations and soccer matches have in the past been occasions of tension and trouble in Northern Ireland. The potential for this existed in 2016.

From 2012-2015, we carried out a major government-funded, qualitative and quantitative, research project on sport and social exclusion in Northern Ireland. One of our central themes was the impact of the North’s socio-political divide and the peace process on the sporting world. Our research chimed with current global interest among policy makers, peace activists, and academics in sport as a peacebuilding tool.

Sport, conflict and peace in Northern Ireland

We know that sport, like wider civil society, is not inherently unifying. It can be an incubator of separation, egotism and prejudice, especially in societies in which the sporting sphere reflects broader political identity divisions. However, at the same time, sport appears to have the capacity to overcome these divisions – in three ways.

The first is through in-group socialisation – empowering marginalised groups and fostering cultures of peace and tolerance. The second is through building social cohesion across identity divides, bringing people from different backgrounds together in a shared enterprise. The third is through its symbolic power. Sport can foster inclusive identities and embed a political transition in the popular consciousness through unified teams, colours and emblems.

In Northern Ireland, a deeply divided post-conflict society, sport has struggled to be a force for unity. Soccer is popular among both unionists and nationalists but the Northern Ireland international team has, in recent years, been associated with the Protestant unionist community and, at times, displays of sectarian aggression. Catholic nationalists tend to support the Republic of Ireland team. Rugby has traditionally been the preserve of a middle class and broadly pro-British demographic.

The governing body of Gaelic sports, the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), was founded as an explicitly Irish nationalist organisation. It has been overwhelmingly Catholic in composition and traditionally held in poor regard among Northern unionists.

Nevertheless, the peace process – which brought an end to political violence and established a cross-community power-sharing government – catalysed a number of evolutions towards inclusivity in the sporting world. The GAA repealed controversial bans such as that on security force membership and has engaged in outreach among the Protestant community. The Irish Football Association made strenuous efforts to create a more welcoming environment for all traditions through its ‘Football for All’ campaign. Rugby too cultivated a more diverse following.

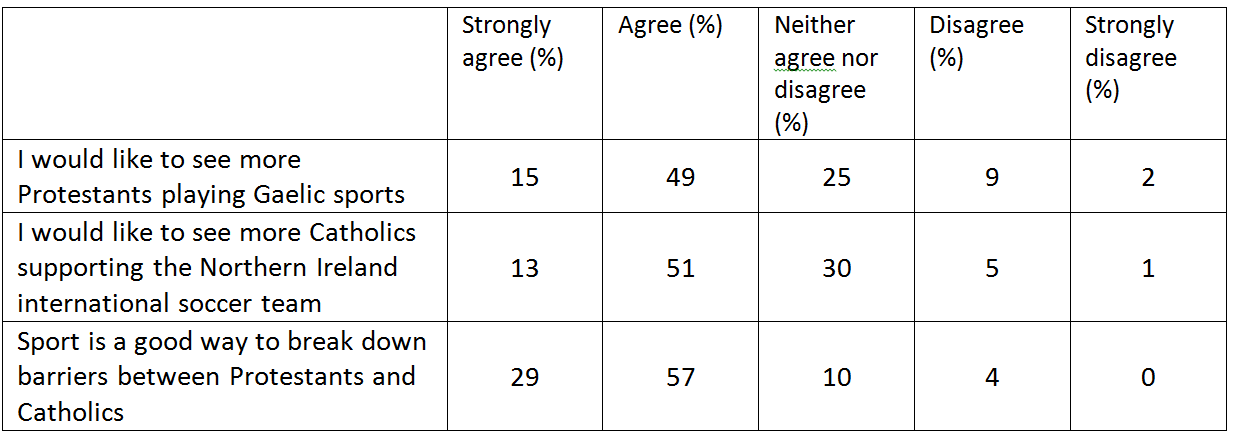

Our survey (n = 1210) found that, broadly, this work of the governing bodies is recognised by the public. Moreover, as shown in Table 1 below, both Protestants and Catholics would like the support bases of sports to become more mixed.

One of our headline findings was the overwhelming public support for the principle of sport as a peacebuilding vehicle. A total of 86 per cent agreed that ‘sport is a good way to break down barriers between Protestants and Catholics’, surely a remarkable finding in a society in which sport has been so implicated in division.

Table 1: Public attitudes to sport and the religious divide

Obstacles to sports inclusivity in Northern Ireland

However, the research also found that sports support and participation continue to follow traditional cleavages. For instance, 31 per cent of Catholics reported watching ‘a lot’ of Gaelic Games on television, compared to only 1 per cent of Protestants.

We also hypothesised the persistence of certain obstacles to greater sports inclusion, in particular, territorial segregation and symbolic contestation – both of which continue in Northern Ireland despite the transformations wrought by the peace process.

Our qualitative research among members of the public found that some people are still reluctant to visit sport and leisure venues in areas associated with the ‘other side’, and that some sports colours and even equipment are still regarded as political markers. The survey found that half as many Protestants as Catholics were willing to attend the main GAA ground in West Belfast.

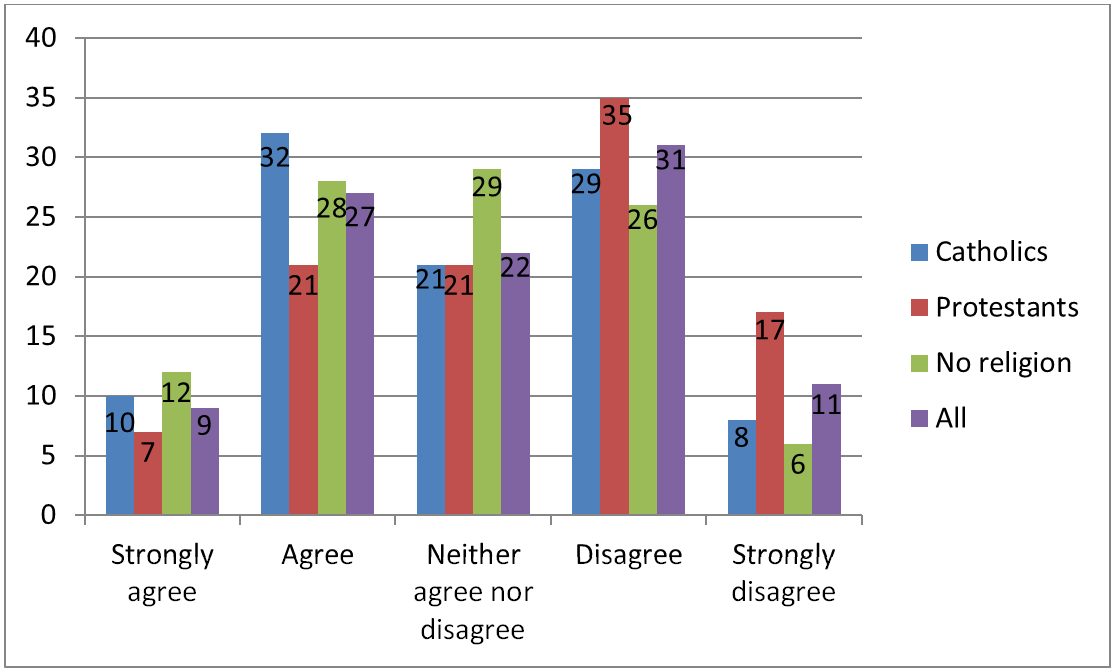

At the same time, sport remains affected by Northern Ireland’s controversial politics of symbolism. The playing of the British national anthem at international soccer matches and the Irish national anthem at some GAA matches has long created a ‘chill factor’ for those who do not identify with those allegiances. On this issue, opinion was closely divided, with slightly more (42 per cent) disagreeing that ‘anthems should not be part of sport in Northern Ireland’, than agreeing (36 per cent). As shown in Chart 1 below, Protestants were more attached to anthems than Catholics.

Chart 1: ‘National anthems should not be part of sport in Northern Ireland’ – results by religious community background.

In sum, things have moved on in Northern Ireland sport, but there remain significant contextual constraints on the extent to which sport can act a force for peacebuilding. The largest sports remain part of a divided civil society which reproduces division. Legacies of the conflict continue to limit the integrative capacity of the biggest sports.

Nevertheless, the Irish contingents’ participation in the Euros (fans from both parts of Ireland were awarded the Medal of the City of Paris for their ‘exemplary sportsmanship’ during the tournament), and the politically-charged centenary celebrations, were all notable for their spirit of mutual respect and an absence of controversy. Hopefully this is an indicator of the progress made in Ireland and that sport, progressively less politicised, can increasingly fulfil its potential as an agent of reconciliation.

—

Note: This blog is based on an article recently published in the British Journal of Politics and International Relations.

David Mitchell is Assistant Professor in Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation, Trinity College Dublin at Belfast.

David Mitchell is Assistant Professor in Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation, Trinity College Dublin at Belfast.

Ian Somerville is Reader in Media and Communication, University of Leicester.

Ian Somerville is Reader in Media and Communication, University of Leicester.

Owen Hargie is Emeritus Professor of Communication, Ulster University.

Owen Hargie is Emeritus Professor of Communication, Ulster University.

The Irish Rugby Team is all Ireland, although dominated by by the Catholic south, and the matches are played in the catholic south, there have been some notable Ulster players in the team. The Football teams being separate goes back to the birth of international football in the same way that the island of Great Britain has three teams England Scotland, and Wales, who additionally have their own rugby teams as well

Two international soccer teams only developed in the post 1920 and mainly after world war 2 not since the 19th century like you suggest.