Successful leaders tend to be big personalities who dominate their party’s organisation, policy development, and electoral campaigns.. But does that control come with a price? Despina Alexiadou and Eoin O’Malley hypothesise that political parties will go through a period of leadership instability and electoral decline after strong leaders step down. Using a dataset with elections under party leaders in nine countries over a 25-year period, and a qualitative case study, they find some evidence for the theory.

Successful leaders tend to be big personalities who dominate their party’s organisation, policy development, and electoral campaigns.. But does that control come with a price? Despina Alexiadou and Eoin O’Malley hypothesise that political parties will go through a period of leadership instability and electoral decline after strong leaders step down. Using a dataset with elections under party leaders in nine countries over a 25-year period, and a qualitative case study, they find some evidence for the theory.

Margaret Thatcher was undoubtedly a strong leader: her influence on the Conservative Party was near-complete. She dominated the party organisation, party policy, and electoral strategy. Under Thatcher, the party got its best ever electoral results and she broadened its base to make it attractive to working class support that had traditionally only voted Labour. In effect, Thatcher created a new coalition that maintained power for almost two decades. She resigned the party leadership in 1990, after 15 years as leader. The Conservatives won a slim majority under her successor in the election 18 months later. It might be thought that after her period of dominance, she left her party in good shape.

Another interpretation might be that in the two decades after she left office the party struggled with internal divisions and poor election results. It committed what one prominent member characterised as ‘a political suicide’. This might have been an indirect result of her dominance. As leader, she suppressed debate on issues that divided the party such as the relationship with the European Union, but those divisions remained, and festered. As leader, she effectively removed any challengers, in part by outliving them, but also by sacking and demoting them. She promoted John Major as her favoured successor even though he was seen as weak and lacking charisma. When he succeeded her, Major won an election the Tories were widely expected to lose, but then he struggled to stop the divisions in the party from bringing down his government. When the 1997 election came, the Conservative Party was annihilated by New Labour. It went through three leaders in quick succession and lost two more elections with only hints of recovery. It was 2010, two decades after Thatcher left, and with the help of the global economic crisis, before the Conservatives managed to govern again, and then only as part of a coalition.

Do strong leaders leave their party in worse shape than they found them? The departure of the exceptional leader might see the party simply revert to ‘normal’. However, strong leaders may also damage their parties; that positive bump may come at a cost. If it happens, what explains it? In our research, recently published in European Journal of Political Research we answer these questions.

Parties face a principal-agent problem, where they can cede the leader too much control, which in some circumstances might be difficult to recover. While the leader and the party obviously share many interests, at times they diverge. The leader may run the party for their own benefit, and their time horizon may differ from that of the party. They may favour immediate office and vote rewards rather than a slower and more sustainable growth.

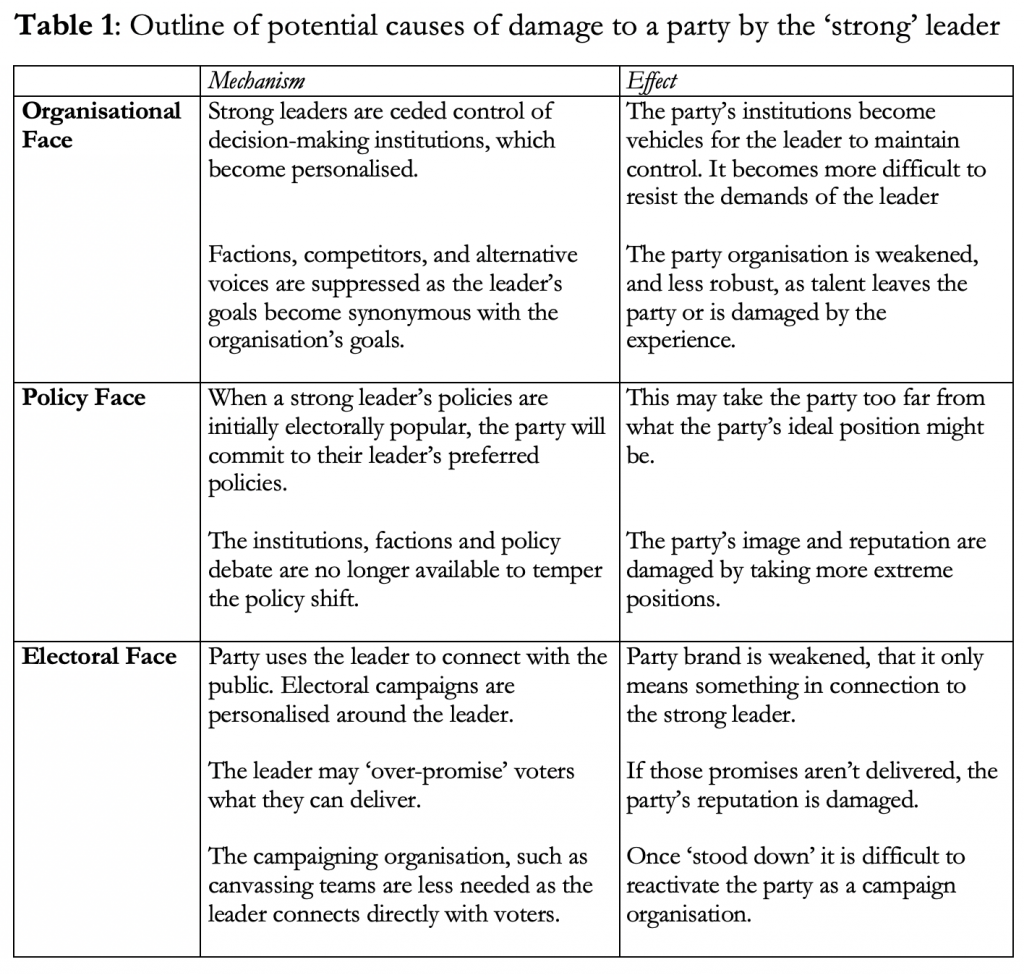

The damaging impact of strong leaders on their parties can happen through a variety of mechanisms in three ‘faces’: organisational, policy, and electoral.

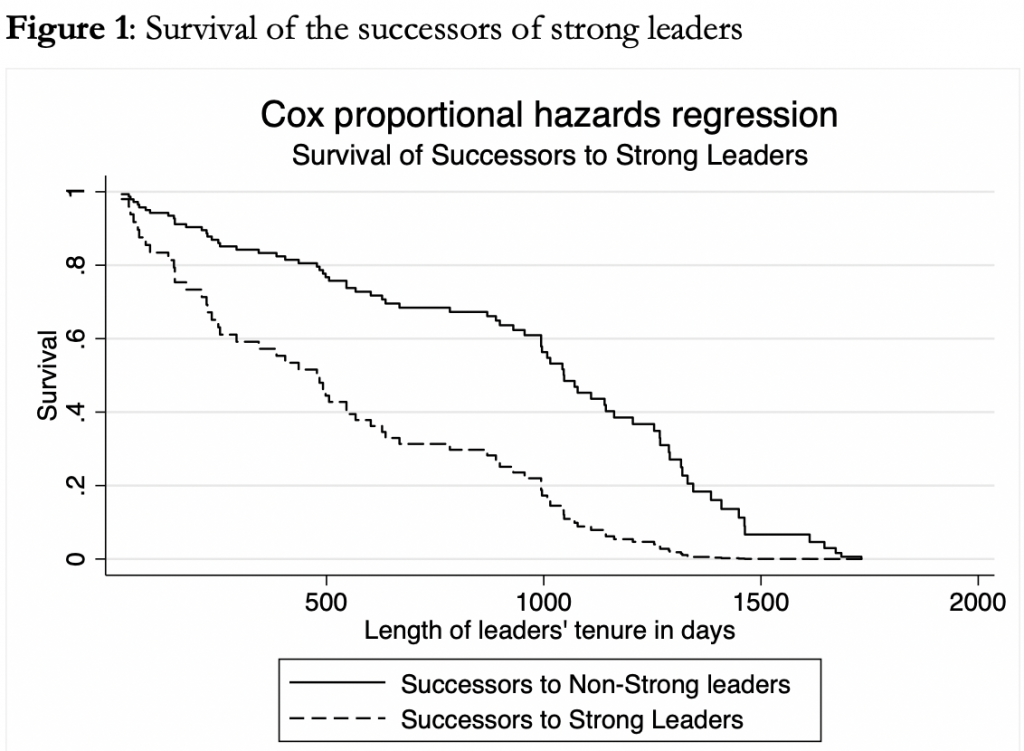

Data limitations prevent us from testing for these different mechanisms, but we can see that parties perform worse than would be expected under successors to strong leaders. Defining a strong leader might be difficult, but operationalising it is even trickier. Strong party leaders are operationalised in two ways, one by length of tenure and also by the leader’s control of the party organisation, as measured by an expert survey. For robustness we use a variety of cut-offs to ensure the results are not biased by the definition of strong leader. The dataset spans 1988 to 2013 with the main unit of analysis election/party. We test two empirical implications of our theory: (1) that the successors to strong leaders will have shorter tenures than successors to other leaders, and (2) that a party will perform electorally worse after the departure of a strong leader. The dependent variable for hypothesis 1 is party leader change and for hypothesis 2 is change in the party’s vote share.

The figure above shows that successors to strong leaders have shorter survival rates. That might be because of the electoral performance of their party. The successors of strong leaders will typically suffer an electoral loss of almost three and a half percentage points. Such a loss is six times above average (the average value for change in the electoral vote is -0.5), and twice as high as the electoral gains of having a strong leader. Importantly, the three-and-a-half point loss is not due to the party’s reversal to its historical electoral equilibrium. Our models control both for the electoral gains of strong leaders, but also for changes in the party leader. These findings rule out the possibility that the negative effect of the successors of strong leaders on vote share is because parties go back to ‘normal’ electoral performance after strong leaders leave, or that it is just a normal ‘cost of ruling’, which we also control for.

This argument was tested on parties in parliamentary democracies, but it might also be applicable in presidential systems, authoritarian regimes, and indeed any organisation, such as a business, suggesting that this is an area ripe for further research.

_____________________

Despina Alexiadou is Senior Lecturer at the University of Strathclyde.

Despina Alexiadou is Senior Lecturer at the University of Strathclyde.

Eoin O’Malley is an Associate Professor (senior lecturer in old money) in political science at the School of Law and Government, Dublin City University.

Eoin O’Malley is an Associate Professor (senior lecturer in old money) in political science at the School of Law and Government, Dublin City University.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash.