Archie Brown draws on his latest book to discuss Margaret Thatcher’s role in the end of the Cold War, which he argues was more significant than commonly believed. He writes that no alternative Conservative leader would have enjoyed the close relationship she enjoyed with Reagan, while it is highly questionable whether an alternative British prime minister would have made such a strong impact on Gorbachev.

Archie Brown draws on his latest book to discuss Margaret Thatcher’s role in the end of the Cold War, which he argues was more significant than commonly believed. He writes that no alternative Conservative leader would have enjoyed the close relationship she enjoyed with Reagan, while it is highly questionable whether an alternative British prime minister would have made such a strong impact on Gorbachev.

The Cold War began just after the Second World War with the Soviet takeover of Eastern Europe. It ended at the close of 1989, by which time those countries had become non-Communist and independent without a shot being fired by a Soviet soldier. Political leadership played a decisive role in bringing about such dramatic change. Central to it was the triangular relationship of Mikhail Gorbachev, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. The most crucial person in the trio was Gorbachev, and by dint of his office and the power of his country, Reagan was his most essential interlocutor. But the most surprising member of the trio was Thatcher.

When Konstantin Chernenko died in March 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev was alone among the ten remaining members of the Politburo (until, as party leader, he was able to bring in several like-minded allies) in seeking radical political reform and in his readiness to transform Soviet foreign policy in the face of resistance from the powerful military-industrial complex and their supporters within the party-state hierarchy.

The Soviet economy in most respects lagged far behind that of the United States, but it was not in crisis in 1985. If, as is commonly assumed, it was economic necessity which forced a change of course, it is odd that it took Gorbachev five years of his less than seven in the Kremlin before he embraced a market economy in principle – and still not in practice. The economy in 1990-91 was in limbo – no longer a functioning command economy but not yet marketized. The Soviet Union had ceased to exist before a market economy was created during Boris Yeltsin’s presidency when, along with a necessary freeing of prices, Russia’s rich natural resources were sold off to pre-selected buyers in crooked deals which a disempowered Gorbachev deplored.

Rather than economic crisis in the mid-1980s forcing radical economic reform, it was political reform that provoked crisis – of the economy and of Soviet statehood. Liberalization and democratization brought to the surface of Soviet political life the accumulated grievances of seventy years and eventuated in the disintegration of the Soviet state, which, contrary to widespread opinion in contemporary Russia, was not a Western policy objective – not even of the Reagan administration.

Rather than economic crisis in the mid-1980s forcing radical economic reform, it was political reform that provoked crisis – of the economy and of Soviet statehood. Liberalization and democratization brought to the surface of Soviet political life the accumulated grievances of seventy years and eventuated in the disintegration of the Soviet state, which, contrary to widespread opinion in contemporary Russia, was not a Western policy objective – not even of the Reagan administration.

In the middle and late 1980s the Soviet Union remained a military superpower just as capable of annihilating the US and its allies in a nuclear war as the US was of destroying the USSR. Mutually Assured Destruction remained the order of the day, although Ronald Reagan agreed with Gorbachev that this precarious balance of terror was indeed mad. To the horror of Margaret Thatcher, they came close to agreeing at Reykjavik in 1986 a policy of ridding the world of nuclear weapons.

Thatcher, however, played a far more significant role in the ending of the Cold War than a ‘realist’ analysis would lead one to expect, given the disparity between Britain’s military power and that of the United States and the Soviet Union. Although nothing was said in public about it at the time, Thatcher and the British government decided in the autumn of 1983 to seek dialogue with the Soviet Union and the countries of Eastern Europe. It was a change of course which led the following year to the Prime Minister hosting Mikhail Gorbachev at Chequers three months before he became Soviet leader.

Thus began the triangular political relationship. Thatcher was already Reagan’s favourite foreign leader by far. That was part of the reason why she became Gorbachev’s most important European partner – until 1990 when the urgency and salience of the German Question meant that Helmut Kohl mattered more (although at no point did Thatcher have as close a relationship with President George H.W. Bush as she had enjoyed with Reagan).

Two Reagan speeches in March 1983 had made the Cold War still colder. In the first of these he described the Soviet Union as an ‘evil empire’ and said that the Cold War was a ‘struggle between right and wrong and good and evil’. In the second, he announced that the USA was embarking on a project to create anti-ballistic missile defence, although for many observers, this Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI, or, in popular parlance, ‘Star Wars’) was a contravention of the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. That was the Soviet view and their leadership saw it as an attempt to give the US a nuclear first-strike capacity.

The Prime Minister shared Reagan’s beliefs in the severity of a Soviet threat and sympathised with his desire to go on the ideological offensive. She had, however, serious worries about SDI. She was careful not to contradict Reagan too blatantly in public, but in private (and with greater tact than she displayed when dealing with Cabinet ministers at home) she made clear her misgivings about SDI.

Up until 1983, both as Leader of the Opposition and throughout her first term as Prime Minister, Thatcher had remained sceptical of the idea that summit talks between the leaders of the two ‘superpowers’ could do any good and she had been wary of closer contact with the Communist world. When Leonid Brezhnev died in November 1982 after eighteen years as Soviet leader, the Foreign Secretary Francis Pym, with whom Thatcher’s relations were frosty, tried unsuccessfully to persuade her to attend the funeral.

The Foreign Office and the Prime Minister’s official advisers were concerned at how overwrought East-West relations had become. The dangers of this were underlined when Oleg Gordievsky, the KGB officer who was working for MI6, warned of worries in Moscow that a forthcoming 1983 NATO exercise, ‘Able Archer’, might be a cover for a surprise attack on the Soviet Union. The plans were subsequently modified to make it clear that this was, indeed, only an exercise. In times of high tension, the dangers of one side believing that the other might be about to launch a surprise nuclear attack were obvious. It would have an incentive to get its ‘retaliation’ in first.

Thatcher dismissed Pym as Foreign Secretary in June 1983 and appointed Sir Geoffrey Howe as his successor. Although she was never close to Howe and their relations deteriorated, initially they were less fraught than with Pym. The Prime Minister, however, held the Foreign Office in low esteem, believing it to be too ready to compromise and not robust enough with the Soviet Union. It took some skilful internal diplomacy by two of the top officials in 10 Downing Street – Foreign Policy Advisor Sir Anthony Parsons and Private Secretary to the Prime Minister John Coles – to persuade Thatcher that it was time to re-examine Britain’s (and thus her) relations with Communist Europe.

The Prime Minister decided to devote the whole of 8 September 1983 to a Chequers seminar on trends in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe and on the UK’s relations with these Communist states, for which the Foreign Office, Ministry of Defence and outside experts would produce papers in advance. The FCO had presented her with a list of experts to be invited, who included mainly people from within their own ranks. These she roundly rejected. The eight who were invited (including the present author) were all outside specialists, seven of them university teachers.

That seminar, which the Prime Minister chaired, was a turning-point. Cabinet Office documents, now declassified, speak of ‘a new policy’ of engagement which would be embarked upon but not publicly announced. The academics were somewhat bolder than the FCO in the range of possible future change they could see occurring, but they reinforced the Foreign Office view that isolating the Soviet Union was counter-productive. Thatcher was persuaded that the time had come for high-level contact with the Eastern half of the European continent. As part of the new policy of engagement, she went to Hungary in early 1984 and, in the course of a single year, Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe visited every Warsaw Pact capital.

In June 1984 an invitation was issued specifically to Mikhail Gorbachev, who had become number two in the Soviet Communist Party hierarchy, to visit Britain. He came in December of that year. His lunch and five-hour discussion with the Prime Minister at Chequers, and subsequent meetings with ministers, Opposition leaders and business people, in the course of an intensive week, gave a huge boost to the new policy of engagement. Charles Powell, who had succeeded John Coles as private secretary, reported that the Prime Minister had been ‘elated’ by the visit. Her interpreter Tony Bishop wrote a mostly perceptive assessment of Gorbachev for the Cabinet Office, delivered on 3 January 1985, in which he remarked on Gorbachev’s self-assurance, energy and personal magnetism, noting his skill in defusing tension ‘in a disarmingly straightforward, unpolemical manner’, with ‘apt, often humorous turns of phrase to register his point’. Bishop added: ‘A roguish twinkle was never far from his eye (he even once winked at me over his shoulder as I interpreted a neat parry of his to one of the Prime Minister’s verbal thrusts)’. Thatcher lost no time in reporting on Gorbachev to Reagan at a specially convened Camp David meeting.

On domestic policy Margaret Thatcher was a deeply divisive figure in British politics. To the extent that she had begun working to improve East-West relations, she was much more in tune with a broad swath of public opinion. Labour Party criticism, and, in more guarded form, that of some of her own ministers and MPs, was that she had too closely aligned herself with Reagan’s Cold War intransigence and had failed to recognize the danger of a drift towards nuclear war. Only a minority of zealots within her own party wanted her to continue to eschew attempts to improve relations with the USSR.

From her Chequers meeting with Gorbachev in December 1984 onwards, Thatcher never missed an opportunity to resume their dialogue. At Chernenko’s funeral in March 1985 she greatly exceeded the time allocated for her meeting with the new Soviet leader and told him that his visit to Britain had been ‘one of the most successful ever’. Her enthusiasm was such that a Foreign Office official, reading the note about the meeting, observed that ‘the PM seems to go uncharacteristically weak at the knees when she talks to the personable Mr Gorbachev’. At the time, that was an untypical FCO response, but by 1989 Thatcher had become even more enthusiastically in favour of engagement with the fast-changing Communist world than were the diplomats and still more pro-Gorbachev than the FCO she had earlier scorned as too soft.

Among those concerned by Thatcher’s trajectory was her Foreign Policy Adviser Sir Percy Cradock, who succeeded Parsons in that role in 1984. Following a much-acclaimed visit the Prime Minister made to the Soviet Union in March 1987, he said he found it ‘harder to talk about Gorbachev with her entirely objectively’, for her ‘formidable powers of self-identification and advocacy were enlisted on his behalf’. Cradock believed that Thatcher became ‘dangerously attached to Gorbachev in his domestic role’.

His apprehensions were misplaced. If Gorbachev’s attempts to achieve a qualitatively better relationship with the United States and with Western Europe, while he simultaneously pursued radical political reform at home, had met with continuing intransigence, it is inconceivable that he could have liberalized and democratized the Soviet political system to the extent he did. He could hardly have declared, as he did at the UN in 1988, that the people of every country had the right to decide for themselves what kind of system they wished to live in. And if Gorbachev and the more benign international environment had not raised expectations in Eastern Europe, both regimes and peoples would have continued to believe that any attempt to move out of the Soviet orbit would be to invite military repression, making a bad situation worse.

There were deep divisions within the Reagan administration over its Soviet policy, with George Shultz and the State Department eager for dialogue with the Soviet leadership but the Defense Department under Caspar Weinberger and the highest echelons of the CIA convinced that little more than cosmetic change was occurring in Moscow and that the threat remained as great as ever. Some officials argued that because of his charm, Gorbachev was an especially dangerous enemy, for he was seducing the Europeans.

It mattered that Thatcher, with anti-Communist credentials as formidable as Reagan’s (he described her as ‘the only European leader I know with balls’), threw her weight behind those favouring engagement with the Soviet Union, telling the president that Gorbachev was a different kind of Soviet leader from any seen before. Thatcher’s significance in the process of the Cold War’s ending was not because she was unique among British politicians in believing that, with Gorbachev in the Kremlin, there was potential for qualitative improvement in East-West relations. Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe was just as alert to these possibilities, Labour Shadow Foreign Secretary Denis Healey even more so. Thatcher’s role was distinctively important because no alternative Conservative leader, still less a Labour leader, would have enjoyed such a close and influential relationship with Reagan. On several occasions he referred to her as a ‘soulmate’, and when she spoke well of someone, he listened.

It is highly questionable, moreover, whether an alternative British prime minister would have made such a strong impact on Gorbachev. He related her criticisms of past Soviet behaviour to the Politburo, telling them they were something to ponder (rather than dismiss out of hand, as his predecessors would have done). Gorbachev was impressed by how closely Thatcher followed Soviet developments and he appreciated the way she spoke positively of the recent changes within the USSR , and of his role, when speaking with conservative leaders in other European capitals and in Washington, and also when she was addressing Soviet audiences. When they met, Thatcher’s vigour in argument was for Gorbachev a plus rather than a minus. He liked her willingness to say what she thought, and he revelled in the cut and thrust. Their animated discussions only strengthened their mutual esteem, as interpreters and notetakers at their meetings have testified.

No British prime minister had more frequent meetings with American presidents than had Thatcher with Reagan and his successor George H.W. Bush. None had as many meetings with a Soviet leader as did Thatcher – not even Winston Churchill with his wartime ally, Stalin. Her official Foreign Policy Adviser Cradock, as we have seen, thought she had become too admiring of Gorbachev. His summing-up of her role in East-West relations has, accordingly, a disapproving edge, yet it points to the surprisingly large part she played during the years in which the Cold War reached a peaceful, negotiated conclusion. Thatcher, observed Cradock, ‘acted as a conduit from Gorbachev to Reagan, selling him in Washington as a man to do business with, and operating as an agent of influence in both directions’.

___________________

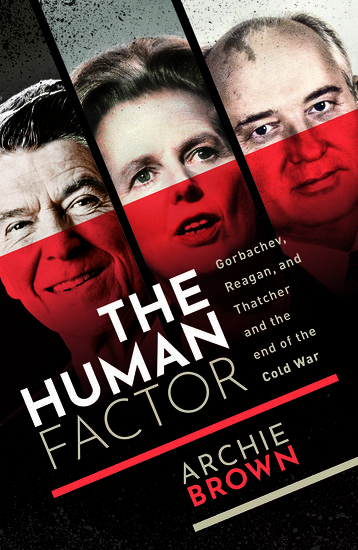

Note: The arguments in this blog are presented at greater length, and the references provided, in the author’s latest book, The Human Factor: Gorbachev, Reagan, and Thatcher, and the End of the Cold War (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Archie Brown, an LSE graduate (BSc Econ., 1962), is Emeritus Professor of Politics at the University of Oxford.

Archie Brown, an LSE graduate (BSc Econ., 1962), is Emeritus Professor of Politics at the University of Oxford.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.