James Mitchell reviews the political parties’ responses to Smith Commission on further devolution to Scotland. He writes that Labour’s dilemma lies in the need to respond to demands for more powers while preventing this resulting in changes in Scotland’s representation at Westminster. Overall, he argues, the Scottish question remains unresolved.

James Mitchell reviews the political parties’ responses to Smith Commission on further devolution to Scotland. He writes that Labour’s dilemma lies in the need to respond to demands for more powers while preventing this resulting in changes in Scotland’s representation at Westminster. Overall, he argues, the Scottish question remains unresolved.

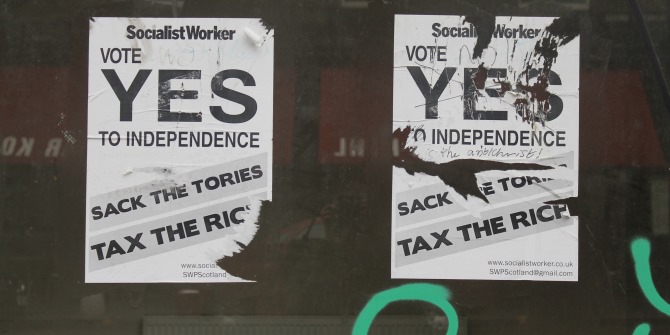

The publication of the Smith Commission report on the further devolution of powers to the Scottish Parliament is further evidence that an answer to the Scottish question remains as elusive as ever. The majority for the union was won by the promise of imprecisely defined ‘extensive new powers’ in The Vow, signed by David Cameron, Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg, just days before the referendum.

After presenting the report, Lord Smith invited representatives of the five parties on the Commission to speak. They all agreed that Smith had performed well in chairing the Commission and all supported the proposals but beyond that there was little agreement. The SNP and Greens noted the limited extra powers being proposed, stressing that these new powers would be insufficient to prevent welfare reform and noted that less than 30 per cent of taxes would be raised in Scotland and less than 20 per cent of welfare spending would be devolved. The Tories, Liberal Democrats and Labour all maintain that the Vow had been delivered but the Tories claimed that the Smith Commission offers ‘A Conservative Plan for Scotland’. Scottish party leader Ruth Davidson later claimed that Smith was, ‘a package designed, built, and delivered by Scottish Conservatives and Scottish Conservative ideas.’ The Scottish Liberal Democrats maintained that Smith offers ‘home rule’, something they had long campaigned for and that they had ‘won the case inside the Smith Commission’ though what Smith offered looked little like that proposed by two previous Liberal Democrat Commissions. Labour was more restrained in its response. Smith was a ‘promise kept and an agreement delivered’. Labour’s concern was less with what Smith proposed for Scotland than its implications at Westminster.

The alliance of Labour and the Conservatives in Better Together had come to an abrupt end when David Cameron spoke outside Downing Street at just after 7am on Friday September 19th. The Prime Minster announced the establishment of the Smith Commission and linked more devolution to wider constitutional reform, notably English Votes for English Laws. For Conservatives, more powers means making the Parliament ‘more responsible’, making sure that Holyrood is responsible for raising money it spends. Smith is seen as less about an extension of powers than as an injection of fiscal responsibility. Conservatives also see Smith as offering an opportunity to address devolution’s asymmetries. The West Lothian Question (WLQ) grows more anomalous with each extension – or perceived extension – of devolution.

For Labour, devolved government was established in 1999 to address the ‘democratic deficit’, to stop Tory rule of Scotland against the wishes of the Scots. Devolution was a reform designed to protect the welfare state and public services in times when the Conservatives were in power in Westminster. Labour prefers to ignore the asymmetrical implications at Westminster fearing that a reduction in the voting power of Scottish MPs would undermine its capacity to govern. Hence, Labour’s opposition to the Prime Minister’s decision to link more devolution and the WLQ and deep unease with extending powers if this provokes demands to address the WLQ.

The main focus has been on Smith’s proposals on taxation and welfare, though there is more to Smith than this. The equation of tax powers with more powers became embedded in devolution debates pre-dating the establishment of devolution. The symbolic significance of tax powers has long outweighed the actual powers on offer. Labour’s proposal to give the then proposed Scottish Parliament tax-varying ‘powers’ in the 1990s proved a symbolic albatross around the party’s shoulders. Michael Forsyth, then Tory Scottish Secretary, portrayed the ‘tartan tax’ as evidence that Labour remained a high tax party at a time when Gordon Brown and Tony Blair were trying to reposition Labour as a party of fiscal responsibility. Labour’s response had been a two question referendum: the first question on the principle of devolution and the second on the symbolic tax powers.

Labour’s dilemma lies in the need to respond to demands for more powers while preventing this resulting in changes in Scotland’s representation at Westminster. It needs to portray the Smith proposals as ‘extensive new powers’ to placate former Labour voters who have been turning to the SNP. But it also needs to avoid provoking a backlash in the rest of the United Kingdom. Labour has been wrestling with this for four decades. This has been reflected in Gordon Brown’s contributions to the debate. During the Smith Commission’s deliberations, Brown warned that taxation powers were a ‘Tory trap’ but he maintained that tax powers represented Scotland having the best of both worlds after Smith reported.

Little wonder Brown has recently argued that Scottish politics ‘has got to reset’. Labour want to move on from the referendum, preferring to avoid the implications of devolution for the rest of the UK. But as Brown leaves the Parliamentary stage, his party has been left with a major problem. The Scottish question remains unresolved and cannot be wished away.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: Joel Suss CC BY 2.o

James Mitchell is Professor of Public Policy at the School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh.

James Mitchell is Professor of Public Policy at the School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh.