Yesterday’s report by the think-tank Reform makes the case for ‘market-testing’ all prisons in England and Wales. The implication is that many existing public sector prisons would not be able to compete with private sector competition, and a large number of public prisons would be transferred into private management. Simon Bastow finds that, as an exercise in ‘thought leadership’, the report is certainly bold and raises interesting points. But is wholesale market testing likely? Not any time soon.

Yesterday’s report by the think-tank Reform makes the case for ‘market-testing’ all prisons in England and Wales. The implication is that many existing public sector prisons would not be able to compete with private sector competition, and a large number of public prisons would be transferred into private management. Simon Bastow finds that, as an exercise in ‘thought leadership’, the report is certainly bold and raises interesting points. But is wholesale market testing likely? Not any time soon.

Underlying the growth of the market for privately-managed prisons has been an implied threat to public sector prisons that if they don’t perform, they will be tested against private sector market alternatives, and if found wanting, will be handed over to a private sector to run. Throughout the 2000s, waves of market-testing have been announced, ‘failing’ prisons identified, and an elaborate bureaucratic exercise ensues to evaluate comparative efficiency and effectiveness.

The fact of the matter is however that up until December 2010, not one market test had resulted in the transfer of a public sector prison to the private sector. It is this lesser-known yet rather striking fact that forms the basis for the argument in the Reform report. Its four key recommendations are:

– all prisons should be market tested, indeed only 17 out of 131 prisons have ever been subject to a test;

– all, regardless of result, should be run on fixed-term contracts so that providers are subject to retendering every so often;

– publish comparable cost and performance data for all prisons; and

– give prisons flexibility to negotiate their own pay and conditions locally.

Sceptics may dismiss these, particularly the first two, as business-as-usual from a right-wing oriented think-tank. They may also sniff a strong lobbying influence of the firms with market share. Meanwhile, prison reform groups will no doubt feel an understandable visceral opposition to the distant threat of wholesale privatisation, the irony here being of course that the private sector has clearly done much to push along reform over the years.

Some degree of healthy scepticism is always useful. But the report, in setting out the arguments in clear (and comparatively speaking, well-researched) terms, raises some interesting points that are worth highlighting.

For a start, it is only advocating market testing and not privatisation. Public sector prisons could submit tenders, and perhaps even in co-operation with private or third-sector organizations. So there is room for innovation in all of this. Indeed, previous market testing exercises have shown how public sector prisons can sit on considerable amounts of latent capacity, and when asked to pull up their institutional socks, they are able to transform themselves often quite quickly from a demotivated baseline to a suddenly transformed organization.

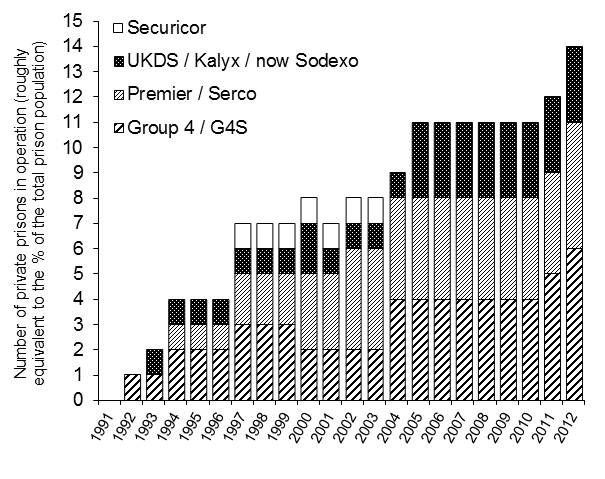

The report also provides a picture of a more mature and well-performing private sector market. The market has grown steadily over the years (see Figure below) and with that has flowed a considerable degree of knowhow and experience into the firms involved. Rather than look upon this sceptically, we might accept the analysis at face value as a sign of the market operating in broadly more successful ways. Indeed the data presented (the Ministry’s own data) underlines this broad shift towards more consistent above-average performance across a range of important areas.

The report is also right to highlight the cultural factors that are now very much part of the private sector way of running prisons. For example, in my own research (see Bastow, 2013 forthcoming), I interviewed many private prison contract directors and senior officials who had made the move from working previously in public sector prisons. Many talked about experiencing the brutality and the constraints of the public system throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and being able to transfer this knowhow and experience into what they see as a much more flexible and ‘can-do’ environment.

So why scepticism about the likelihood of such a bold move? Well, as suggested above, the history of market testing in England and Wales does not bode well.

From the market side, the incentives for firms to bid for existing public prisons have often not been sufficiently strong. Indeed, firms would find it difficult to replicate the kinds of regimes in archaic Victorian local prisons that they are running in their new and purpose-built infrastructure. And it has been a long-running issue for firms that there is not a level-playing field in terms of the public sector’s greater ability to cover comparatively more expensive public sector pensions of staff transferred to the private sector. As one former senior NOMS official told me:

“Why would the private sector want to run failing prisons? They want to run good prisons, not really bad ones. It’s all very well for the Prison Service to threaten these prisons with transfer, but they don’t seem to realise that the private sector doesn’t want them in the state they are in and the conditions they come with.”

On the government side, often the decision to introduce more extensive market testing, or indeed to decide to transfer a prison as a result of a test, has come down to ministerial decisions, and ministers, particularly Labour ministers, have often been reluctant to take on the POA. Similarly, the senior officials in NOMS making the decisions about whether ‘failing’ prisons have shown enough improvement to avoid being taken to market test are the very same officials whose job it has been to defend the public sector against the private challenge. These political and institutional constraints on both ministers and senior officials are important factors in explaining latent internal resistance to market testing.

It is these very same political constraints that are now coming to bear on the current ministerial team. Since May 2010, the prison system has been through a wave of radical policy reorientation involving some important upheaval. Not least was the decision under Ken Clarke to transfer Birmingham prison to G4S in December 2010, one of the largest and most militant in the estate. As the report has pointed out, under Grayling, there has been perhaps a new stage of ‘retreat from competition’ as deals for ‘whole prison’ contracts have been taken off the table. It is likely that this retreat is a reflection of the constraints on him managing this on-going relationship with the POA post-Birmingham (not to mention their Lib Dem coalition partners).

The government’s response has been to push for national wage setting and selective contracting out of ancillary and rehabilitative functions in prisons. It may be that there is much to gain from innovation and involvement of the private (or third) sector in these areas. One only has to spend a few hours in an average public sector local prison to see that the system has managed to sustain, indeed normalize, obsolescence and inefficiency in many areas.

On the other hand, carving up functional parts of the system and running them through new contracts has potential to increase transaction costs and introduce new kinds of gaming by actors involved. In the area of rehabilitative services, for example, giving responsibility to contractors to ‘do rehabilitation’ in prisons runs the risk that any wider focus on rehabilitation across the public sector becomes diluted and seen as something that is a contractor’s problem rather than a central part of the culture of the prison as a whole.

There is complexity in all of this that will not be easily resolved by simplistic demands for wholesale market testing. Clearly, it is unlikely that the prison system is no time soon going to be tested en masse – but this should not discount innovative approaches around SLAs and contracting. Even if a visionary Minister wanted to have a go at the wholesale option, the political and logistical constraints on her or him would be too great. But the report is an interesting contribution to the debate. Ten years ago, it could have been more easily dismissed. But in today’s context, the underlying rationale cannot, like it or not, be dismissed so readily.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Simon Bastow has a book forthcoming on the England and Wales prison system – ‘Governance, performance, and capacity stress. The chronic case of prison crowding’. Published later in 2013 by Palgrave McMillan. He has been a Senior Research Fellow at the LSE Public Policy Group since 2005. He was previously at the School of Public Policy, UCL (now the Department of Political Science). He completed his PhD in political science in April 2012, looking at chronic capacity stress and crowding in the England and Wales prison system.

Why don’t private prisons tell the truth,you are costing the tax payer millions while making a profit out of people’s misery.The public sector has been given 2 years to make savings.Under Fair and Sustainable the private sector will be squeezed out leaving the public sector to run prisons as we have for hundreds of years without profit.

The Reform report says nothing we didn’t already know. When I sat as one of the two external members of the government Inquiry into the management of the Prison Service in 1996-7 (as part of the follow-up to the Derek Lewis affair) it was already apparent that privately managed prisons had some performance advantages over the HMPS run ones. It appeared to be mainly because of their different relationships with staff. But it was also apparent that anything more than about 10% of actual prison establishments being run by the private sector was politically unacceptable and was never likely to happen. If the state retains the right to deprive people of their liberty, it is unlikely ever going to be acceptable for that function to be fully privatised. Reform are pursuing a lost cause. In this case, values will always trump performance.

Thanks, Colin, for the comment. I agree that the politics will usually trump the performance arguments. It is interesting that during the mid-1990s the general feeling amongst private sector operators was that their market should increase to 25%, but the feeling in government was closer to 10-15%. That was 15 years ago and we are not much further on despite the strong pragmatic commitment under Labour to push contracting. Undoubtedly, Labour ministers were constrained by the POA (and public opinion) in terms of pushing the market share up towards 25%. And even if Conservative ministers may be ideologically inclined to go that way, they too are experiencing exactly the same constraints.

Having said that, however, there are various reasons why the situation has moved on from that in the mid-1990s. For a start, the private sector market is undoubtedly more mature and has shown that it can operate safely and relatively decently, even if private local prisons do get away with pushing the crowding limits. There may be scope therefore to push the market share up towards 20%, and give away another large public sector local prison in London.

Also, the information environment in NOMS has improved dramatically in the last ten years, making it much easier to track comparative prison performance. A former NOMS official told me that they had been asked in the early 2000s by a prisons minister which was their ‘best’ prison. The Prison Service was not in position to say, apparently, because they didn’t have the data. Ten years later NOMS performance staff are processing vast amounts of data internally. Some of this is seeping out slowly. Indeed, the Reform report’s analysis on rehabilitation rates reflects this greater public availability. That would not have been possible five years. Believe me, I tried to do it.

So wholesale market testing is both unrealistic, and probably would actually have detrimental effects on the sector as a whole. But we should not ditch the idea of some sstrategic market testing altogether.